Illustration by Michele Abercrombie

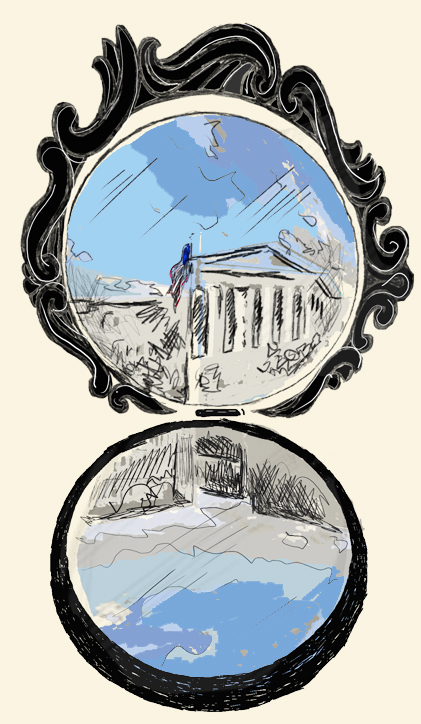

Unlike the adult courthouse that stands beside it, the Clayton County Juvenile Court building has no grand columns or dominating facade, but rather a wall of windows and a lobby its creator likens to a Hilton Hotel.

The design of the non-traditional juvenile courthouse in Jonesboro, Georgia, was spearheaded by Judge Steven C. Teske. He and the architects he worked with designed the space to reduce anxiety, comfort the traumatized and encourage collaboration between youth, justice officials and community leaders. The building reflects the judge’s commitment to restorative justice principles: he focuses on making human connections with young offenders in an effort to address the root causes of their behavior rather than merely punishing them.

“You want to be encouraging,” Teske said. “The only way you’re going to help people change their behavior is through positive relationships.”

The building, officially called the Clayton County Youth Development & Justice Center, was constructed in 2012 to house the jurisdiction’s forward-thinking system, which has become a national model for juvenile justice reform.

Teske has served as a juvenile judge since 1999. He inherited a system that was unorganized and overwhelmed with complaints from schools. In 2003, as a part of the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, Clayton County –– the sixth largest of Georgia’s 159 counties –– invited community members and parents into the courthouse along with the youth to find solutions to the problems plaguing their lives and giving rise to their behavior. According to the county’s annual juvenile court report, since these innovative programs were enacted, detentions have declined by 70%.

According to Margaret J. King, director of the Center for Cultural Studies & Analysis think tank, traditional courthouse architecture –– like that of the Harold R. Banke Justice Center next door to Teske’s building –– evokes a specific feeling to the public.

“Courthouses are intended to be imposing, to inspire awe, and when they are typically classical and overscaled, calculated to make us feel small and insignificant in order to communicate their authority and power,” she said. “They radiate the majesty and gravity of the law.”

This is just the type of building Teske did not want to build. One of his central directives to the designers of the facility, he said, was, “I don’t want a traditional courthouse.”

For Teske, the physical differences between the juvenile court building and the adult one next to it mirror the philosophical differences in the courts’ goals. He said his system is not intended to dominate the people involved with it, but to invite them in to solve problems cooperatively.

“In the adult system it’s very simple: they’re being punished for a crime,” Teske said. “In the juvenile system, it doesn’t work that way. The kid’s brain is still under neurological construction.”

Architect Melissa M. Farling, an adviser for The Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, emphasizes the role design can play in justice systems which aim to be “cooperative and collaborative.” The design of physical spaces, she said, “impacts our physiology –– I mean everything: emotional, psychological, neurological.”

In recent decades, researchers have accumulated a mountain of evidence supporting the central idea guiding the design of Teske’s courthouse: spaces influence people’s bodies and minds.

In one classic 1984 study, researchers split up patients recovering from surgery into two otherwise identical rooms with entirely different views out their windows: one a blank brick wall, the other a sunlit scene featuring leafy green foliage. Patients in the latter room, on average, recovered a full day earlier than the other group and required fewer strong narcotics to ease their pain.

“People who come into [the facility] are traumatized,” Teske said. “And when they are intimidated, they tend to shut down. And when they shut down, they don’t talk. And we got to get them to talk about what their issues are.”

The juvenile justice building’s lobby is flooded with sunlight and filled with art from school children of all ages in the community. Large windows offer views of a courtyard with trees outside.

According to environmental psychologist Sally Augustin, these design features reduce stress, boost mood and encourage broad thinking. This type of thinking, she said, is critical to “problem solving and getting along with others.”

Augustin said the design of a place has an especially pronounced effect on people’s minds in high stress or high stakes situations. In these cases, like when a child is appearing at juvenile court, she said, people “look for clues in their world” to orient themselves and make sense of the situation.

At Teske’s facility, interview rooms where young people meet with probation officers and other officials are housed in private spaces on the first floor. This way, the adults come to the child, which Augustin said can offer them a sense of comfort and ownership of the place. This, she said, indicates to the young people in the courthouse that they can work with the system cooperatively.

Augustin said this feature can impact the power dynamic between the young person and justice worker who sees them. The adult will always have the power and authority, she said, but “things get equalized, to a certain extent” when the young person is allowed to claim their territory before the meeting begins.

Tucked away at the top of the building is Teske’s domain, the courtroom. It is the least accessible part of the facility, because, he said “it is the least frequented place” there. He doesn’t want to judge young people involved in the juvenile justice system, he wants to talk with them.

Since starting his dialogue-based reforms, Teske has seen less and less activity on the top floor –– exactly the goal of his columnless, conversation-oriented system and building.

Anthony J. Wallace is a master’s student at Walter Cronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University. A Phoenix native, he is a writer and multimedia journalist, producing articles, podcasts, videos, and photos for a variety of publications including Phoenix New Times, Phoenix Magazine and The Hertel Report. Through his own experience with chronic illness, he became fascinated with health care, disease and its intersections with politics and culture. Before pursuing journalism, he earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Northern Arizona University and spent nearly 10 years in a touring alternative rock band.