Photo illustration by Nicole Sroka

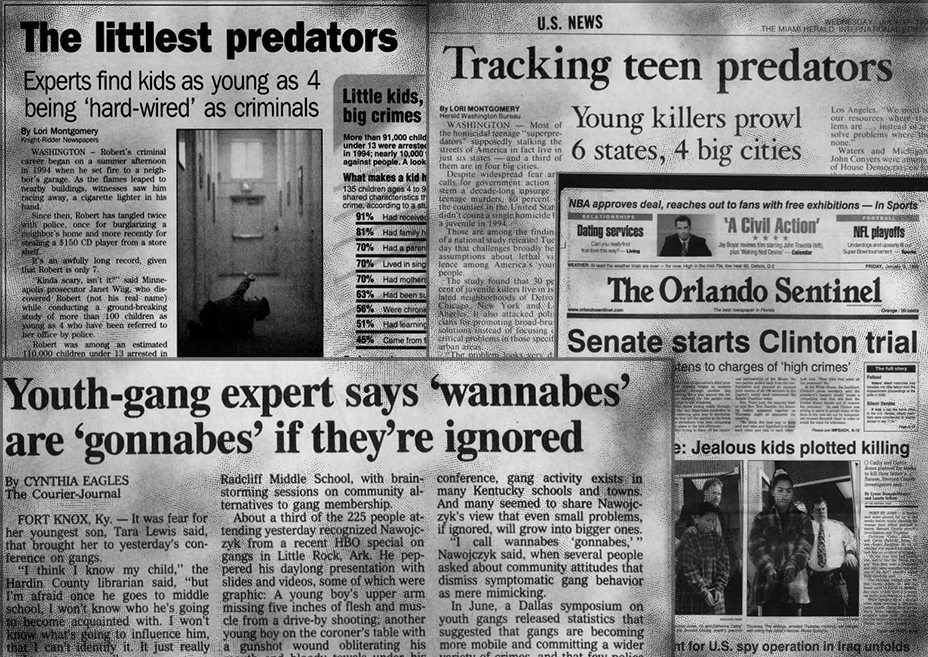

During the mid to late 1990s, a fear of violent youth crime swept the nation, fueled by inaccurate estimates from criminologists and media reports.

A substantial rise in youth violent crime in the 1980s through early ‘90s prompted criminologist and then-Princeton University professor John DiIulio to write an article in 1995 predicting that a new breed of juveniles were going to terrorize the nation: “super-predators.”

The youth violent crime rate began to significantly decrease that same year, but by the time this was recognized, the damage had already been done.

James Fox, a criminologist and professor at Northeastern University predicted the same thing as DiIulio. In his report for the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, he forecasted that by 2005, the juvenile violent crime rate would increase by 20%.

At the time, DiIulio and Fox said their logic made sense. The youth violent crime rate was already at 30 per 100,000 in 1994, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and with even more children being born as a consequence of the baby boomer generation, they said the rate would rise with the population.

But, DiIulio and Fox didn’t account for outlying factors that could have contributed to crime in their estimates. Instead, they said these children were born different.

The youth crime rate fell faster than it rose. In 1995, the same year DiIulio first coined the term “super-predator,” it had already fallen by nearly 6%, and continued to fall at this rate until it reached about 11 per 100,000 in 1999, where it has flattened out.

A report by the National Consortium of Violence Research found that the quick increase and decrease of youth violent crime during this time could be attributed to the crack cocaine epidemic, an economic recession, high unemployment rates and other factors.

Fox said in an interview with News21 he doesn’t regret what he said because he helped raise an alarm about the need for measures to prevent youth crime, like after school programs, and to an extent it worked. He noted that many cities implemented preventative crime measures, but acknowledged that the conversation created a lot of harsh and punitive laws.

DiIulio, who now teaches at University of Pennsylvania, later said he regretted spreading his “super-predator” theory, but was not available for an interview. The U.S. Department of Justice deemed his theory a myth in 2000.

Legacy on Life

The Bureau of Justice Statistics first began tracking the number of youth in adult jails in 1993, when there were roughly 4,300 kids incarcerated. By 1999 — six years later — this number more than doubled. Nearly 9,500 kids were in adult jail, and 91% of them were being tried as adults.

Catherine Jones was one of these kids.

Jones was 13 years old when she and her 12-year-old brother, Curtis Fairchild, were among the youngest children to be charged with first-degree murder. On Jan. 6, 1999 they shot and killed her soon-to-be stepmother, Sonya Speights, in their Brevard County, Florida, home.

Her uncle, a convicted pedophile who lived in the same home, had been sexually abusing her since she was five. She told a pastor about the abuse, and it was reported to the state. She remembers nothing changing after the abuse was reported. She remembers her father not believing her.

But one person did believe her: Her brother, because it was happening to him too.

Jones said when Fairchild told her that he was being abused, her 13-year-old mind couldn’t think of an escape other than death. She remembers being in the shower, and her uncle coming into the bathroom and opening the shower curtain to masturbate. When he finished, she said he left 35 cents on the toilet seat. Her father and stepmother were in the other room.

“And I vowed in my head that now, to me, everyone’s responsible,” Jones said.

When she was arrested, she said she told the investigators and her lawyers about the abuse. In most cases, this kind of trauma would have been a factor in deciding if she and her brother would be charged as adults and, if found guilty, how long their sentence would be.

Tod Goodyear, who was one of the homicide investigators on the case and now the public information officer for the Brevard County Police Department, said he remembers the abuse coming up, but that his job was to investigate the homicide. He said Jones told him their motive was that Speights was getting in the way of the children’s relationship with their father, but Jones said she did not say this.

Local headlines read, “Police: Jealous kids plotted killing” and “Shooting ends fight for dad’s attention.” Jones said she remembers watching herself be described on television news as “remorseless” and “not appearing to have emotions” because she didn’t cry in court hearings. But she said this reaction was her usual defense mechanism to cope.

“From the time that I was arrested and I received that infamous label of a super-predator or a child killer or the youngest female killer, I was never referred to by my name in headlines,” Jones said.

Legacy of Language

The way Jones was described was exactly how DiIulio and Fox described the incoming cohort of juvenile criminals.

Fox said he didn’t agree with the word “super-predator,” but instead used phrases like “teenage blood bath” and described children, particularly teens living in “urban” areas, as having “little to live for and to strive for, but plenty to die for and even kill for.”

Fox said his use of the super-predator rhetoric was not racist because the increase of violence he predicted was among both white and Black youth. Critics disagree.

“If you introduce a framework that dehumanizes a population, you are nevertheless joining ranks with a discursive practice that has long, long existed,” said Geoff Ward, a professor at Washington University who focuses on the racial politics of social control.

This dehumanization is a mechanism of “othering,” Ward said, and people, especially white people, use it to justify and protect themselves from what is happening to other populations.

Ward said this concept isn’t new. This framework was used when European colonizers called indigenous people “savages” to justify taking their land. He added that it is used today by the current administration to rationalize harsh immigration policy by labeling certain immigrants as rapists and criminals.

James Forman, a law professor at Yale University and expert on mass incarceration, said people were already scared from the spike in crime rates in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, and fear of crime is often a result of the systemic racism the country is built on.

“The willingness to think of Black people as the other, as the criminal element, is what made people able to mobilize on that fear, to create these harsh laws,” Forman said. “Because people thought, ‘Well, these harsh laws are aimed at somebody other than my child.”

Black and Latino youth were not only disproportionately incarcerated during this time, but they were also disproportionately shown on television and in newspapers being arrested for crimes, reinforcing negative racial biases without explicitly saying it, said Ward. And they still are.

Jones said when she watched news reports that depicted her as a “remorseless” super-predator at 13-years-old, she began to believe it.

“I didn’t realize I was numb because of everything I had went through,” she said. “I really thought maybe I was just incapable of feeling.”

Legacy of Law

In the 1996 election, both Republican Bob Dole and Democratic incumbent Bill Clinton ran on platforms to be “tough on crime” and restore “law and order.”

A 1996 speech by Hillary Clinton came into headlines in 2016, another election year, when a Black Lives Matters activist interrupted a private campaign event to ask for an apology for the mass incarceration of Black Americans under her husband’s administration.

“These aren’t just gangs of kids anymore. They are often the kinds of kids called ‘super-predators.’ No conscience, no empathy,” Hillary Clinton said in the speech.

Advocates say initiatives under the 1994 Crime Law passed by President Bill Clinton contributed greatly to mass incarceration, and the super-predator myth added to it by funneling more people, specifically Black and brown Americans, into the adult prison system for longer periods of time.

A U.S. Department of Justice study found that legislatures in nearly every state revised or rewrote their laws to make it easier for jurisdictions to transfer kids to adult court through lower age limits, automatic transfers and handing off the decision-making from juvenile court judges to criminal prosecutors.

It took 21 days for the courts to decide to transfer Jones and her brother to the adult court system, where they were charged and convicted. As soon as their case moved to adult court, they were treated like adults.

At 13, Jones said she didn’t understand what the right to remain silent really meant. She signed a plea bargain for second-degree murder that gave her 18 years of incarceration and life on probation. She was told if she didn’t, she would spend the rest of her life in prison.

She was sentenced within 10 months without having a trial.

Over 75% of the over 2,800 people currently serving life sentences without parole for crimes committed under the age of 18 were incarcerated during or after the 1990s, according to the Campaign for Fair Sentencing of Youth.

The campaign also found that Black children are sentenced to life without parole at 10 times the rate of white children, fueling the racial disparities seen in both the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems.

“You cannot separate the creation of a justice system from the society that’s asking it to be created,” said James Bell, founding president of the Burns Institute, which works to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system.

Legacy to be changed

Laws passed in response to the super-predator myth are slowly being reversed. The 2012 landmark Supreme Court case Miller v. Alabama ruled that it is unconstitutional to sentence a child under 18 to life without parole without considering how children are different from adults.

Steve Drizin, clinical director of the Center for Wrongful Convictions who has experience representing juveniles charged with serious crimes in the ‘90s, said he began to see a slight reversal in these punitive laws when the juvenile death penalty was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2005.

Around this same time, he said, more robust research on brain development emerged, showing that children’s brains don’t fully develop until their mid-20s, which helps explain impulsive crimes and those that are reactions to trauma.

While there have been great strides to repair the impact the super-predator myth had on juvenile incarceration, advocates say there is still work to be done. There are 13 states without a minimum age to try a child as an adult and about 95,000 children are housed in adult jails and prisons each year.

Jones was released in 2015 when she was 30 years old. She said she left the worst part of her life behind her.

“The air smelled different. It felt different,” she said. “Once you got past that control room with no barbed wire, it was like everything became so big.”

Jones said when she was first in prison, she thought she deserved to be treated like a “super-predator.” She said the guilt of taking away the life of her stepmother destroyed her, and she lives with it every day, but now it fuels her to create change.

Jones now works full-time at the Campaign for Fair Sentencing of Youth advocating for children to be treated as such in the criminal justice system. She said children need to be held accountable for their actions, but they need to be held accountable in age appropriate ways.

Between the campaign and volunteering with Fresh Start Ministries to support abused women, she juggles two toddlers. She said she wants her kids to have the security she didn’t have, and wants them to know she will always be there for them.

“Instead of a super-predator, I’m a super-mom,” Jones said.

Source art courtesy of Newspapers.com

Chloe Jones is a master’s student in the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. In 2019, she earned a bachelor’s degree at Cronkite with minors in philosophy and Spanish. Jones, who is from Tempe, Arizona, previously covered sustainability and immigration for Cronkite News, the news division of Arizona PBS, where she reported from Mexico, Peru and Panama. Her 2019 multimedia investigation of a sewage crisis on the Mexico border won first place awards from the Online News Association and Associated College Press. A photo of migrants in Peru won a Society of Professional Journalists’ Mark of Excellence regional contest. Jones also worked for KJZZ 91.5, the NPR affiliate.