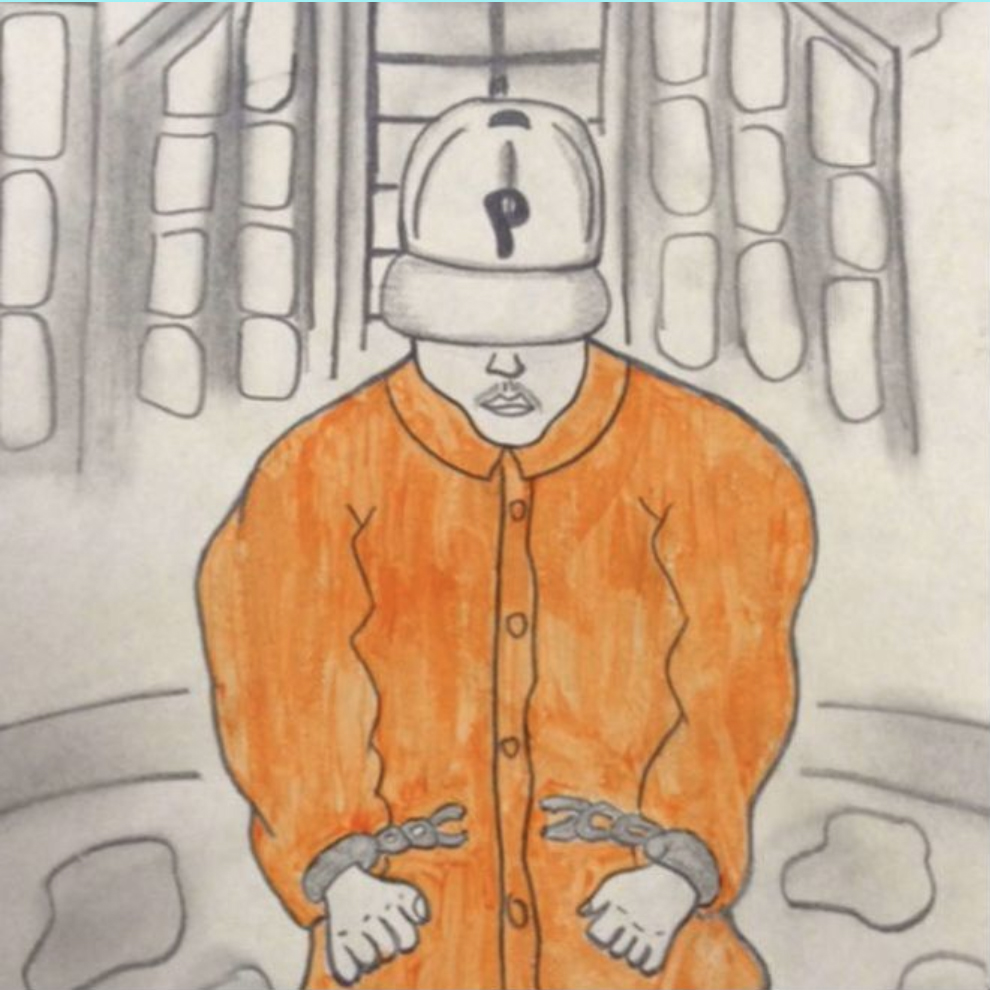

Illustration by Michele Abercrombie

Zakiya Cherif of Philadelphia was at work when she received the call that her 17-year-old son, Zaphir Reddy, had been arrested.

“I was scared. I was really scared. I feared for my son’s life,” Cherif said.

Cherif’s life quickly changed. On top of being heartbroken, she said the costs have been enormous because of legal fees and all the time she has taken off work for court dates and visitations. Before COVID-19, she was visiting him once a week, renting a car to drive 2 1/2 hours to the Loysville Youth Development Center in Loysville, Pennsylvania, where he has lived this past year. Cherif’s son was sentenced for two years in 2019 for a crime she didn’t want to discuss.

She also pays for extra food and toiletries.

“There is not enough food being given to the children,” Cherif said. “You have to order it through a system that they have set up with the prisons.”

Because of the enormity of the financial, emotional and psychological burdens on families of those incarcerated, small and large nonprofits around the country often step in to try to fill the voids, to help parents navigate the complicated justice system.

“What you see is a juvenile justice system that does not allow for family input or family participation. Very few juvenile justice systems work with families,” said Liz Ryan, president and CEO of Youth First Initiative, a national advocacy campaign to end the incarceration of youth and direct resources to community programs for youth.

Justice for Families reported in a study that 75% of families of kids in the juvenile justice system face financial barriers related to transportation and time. Fifty-one percent said their annual household income amounts to less than $25,000, while the national median income for families is twice that.

Single parents like Cherif struggle more with only one household income to pay the price of incarceration. One study indicated that more juvenile offenders come from single-parent families, particularly mother-only families.

The Youth Art and Self Empowerment Project in Philadelphia, also known as YASP, is Cherif’s first support system. YASP staff members support mostly Black and brown families, helping parents understand the justice system legal jargon and processes, filling the courtroom with support during court dates, and helping their children reenter the community after incarceration.

“They kept note and kept me focused and paid attention to things that I wouldn’t know to pay attention to,” Cherif said. “So that was my support.”

“And then my church family made sure they attended the trial dates,” Cherif said. “They kept my son in prayer, they checked on them. They visited him. They wrote him letters. And my family, too, they started to step up as well.”

Cherif began volunteering for the Philadelphia group after her son was incarcerated, as payback for the help it provided her. She became a member of YASP’s “youth participatory defense hub” when she realized how limited support there is for people who look like her son, an African-American male.

“You feel like you failed to keep your child away from the legal system,” Cherif said.”… He’s already got several strikes against him and then to add the incarceration on top of it.”

She now sits with other mothers and fathers in court and tries to help them through a juvenile justice system that she said doesn’t work for many of them. She doesn’t want other moms or dads to go through what she did.

Across the country, In Wichita, Kansas, Tyler Williams is a founding member and a community organizer with Progeny, a youth/adult partnership focused on alternatives to youth imprisonment. Williams and others in this youth justice advocacy group also mentor kids and get them involved in juvenile justice reforms in the community.

His passion for advocacy and reform grows from his own experiences.

Starting at 13, he spent six years at a juvenile facility. He now works with youth at risk of getting in trouble with the law. He also helps those readjust after being in detention.

After his release at 19, he and other formerly incarcerated youth worked to build Progeny.

“We were really young, really just trying to make a change and a difference in our community, as youth who have been directly impacted by the system and have firsthand knowledge,” he said.

They saw problems that a lot of youth are facing due to what Williams describes as holes in the justice system.

“We wanted to be out there, try to make a change, give the youth a voice – to enact policies that are a lot more beneficial, not only to youth, but to also … the communities and victims as well,” Williams said.

Earlier this year, the advocacy group created a “COVID-19 call to action,” requesting that Kansas develop a better plan for keeping youth safe in juvenile detention facilities. They called for such things as halting new admissions, finding alternative living options, and providing immediate medical care to detained youth.

“While some jurisdictions have canceled visitation, we believe that this is not a time for youth to be separated from their support systems,” said Williams in July. “This will only exacerbate mental health issues and further isolate youth.”

Another Progeny effort is the “Invest Don’t Arrest” campaign, which is working to reimagine the juvenile justice system and reinvest in community alternatives. Williams said one of Progeny’s goals is to close Kansas’s last youth prison, investing those funds into the community instead and keeping families whole rather than sending kids to detention facilities.

Ryan of Youth First Initiative said the best, most effective programs for young people across the country are ones that work with the whole family, not just with the young person.

“It’s really a question of are we willing to do the right thing here and keep kids together with their families? And invest in youth and their families.” Ryan said.

Another organization, Youth Advocate Programs Inc., or YAP, a nonprofit with offices nationwide, uses a “wrap-around” model to support families impacted by their childrens’ incarcerations.

Jeff Fleischer, president and CEO of YAP, explained that his organization receives a small portion of money that originally would have gone to incarcerating youths and instead invests in the families of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated youth. The group mentors, counsels and helps both kids and parents find jobs.

“We’re the alternative to incarceration,” Fleischer said.

Resources are redirected from incarcerating young people and redirected to serving the entire family, Fleischer said. Advocates are assigned to a whole household and are available to provide support to not only the youth, but the parents and siblings as well.

“They have a team of people now that are supporting them. They have an advocate that’s in their home for 10,15 hours a week,” Fleischer said.

Tyler Williams agrees the approach in reforming juvenile justice today has to go beyond the youth. It needs to be community-based, he and other nonprofit leaders say.

“In order to help heal not only yourself you got to heal the other people around you because it’s a community,” Williams said. “And if there’s one bad thing in the community, then we need to help fix it.”

Source for art: Artwork created by youth during a Youth Art & Self-Empowerment Project workshop

Michele Abercrombie is a multimedia, photography and design master’s student at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Originally from Boston, Abercrombie worked in elementary education before deciding to pursue visual storytelling professionally. During the fall of 2019 she attended the Eddie Adams Workshop XXXII and she is a recent recipient of the Mary Lou Foy Still & Multimedia scholarship. Her work has been displayed at the World Financial Center Courtyard Gallery in New York City and the State Transportation Building in Boston.