Photo illustration by Nicole Sroka

Each of Richard Ross’s photographs starts with a knock on a kid’s cell door and an introduction to his work. Then he hands them his camera for them to take a picture.

“You trust them with it,” he said.

By giving his camera to the children he photographs, Ross invites them to become participants in the image that they create together. For the past 15 years, Ross has traveled the country on a mission to document children and teens in solitary confinement.

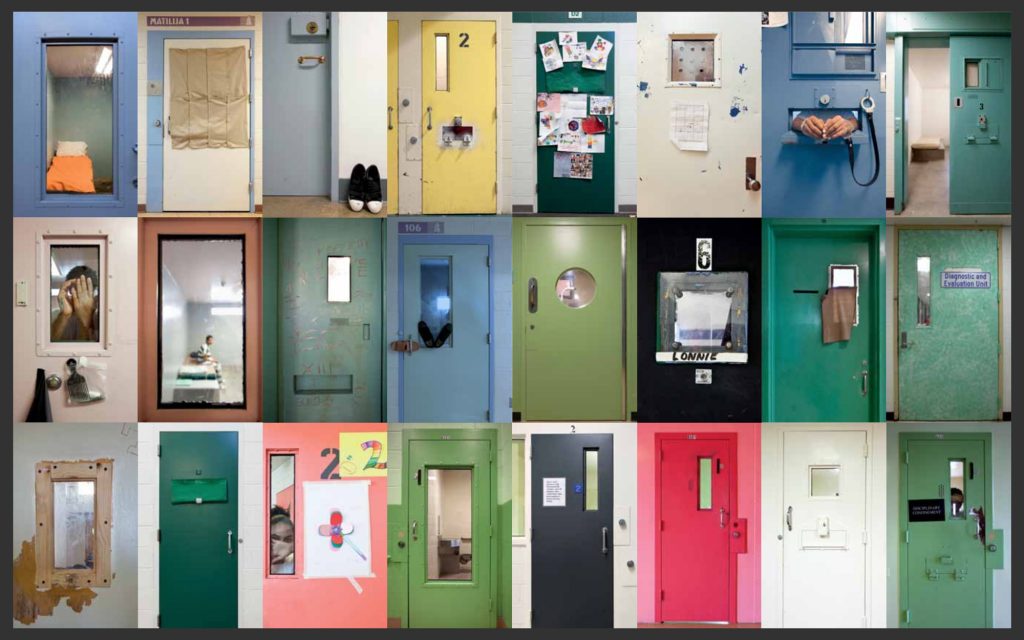

His award-winning series “Juvenile In Justice” captures the images of more than 1,000 children who are incarcerated at over 300 U.S. detention centers. His photos illustrate the ways in which U.S. detention centers manage kids through detainment, treatment and punishment. For Ross, the use of solitary confinement is an indicator of a failing juvenile justice system.

“I’m not really the activist,” Ross said. “But if you’re pushing legislation or policy, I have the images. I have the audio. I have the library to help you get your message out.”

Despite a lack of data, anecdotal reports from advocates across the country suggest the practice of solitary confinement is far too common throughout the juvenile justice system. Ross said he believes the data exist in a “cold fluorescent light” and that the images and voices of the kids are essential to building empathy and enacting change.

Ross challenges his viewers to ask themselves how they would react if they came across a kid locked in a closet. For him, the answer should be easy.

“You would immediately take them out and comfort them,” he said. “You would try and find out who put the kid in the closet and what their thinking was. You [would] try to hold those people accountable. Then you would also try to do something to explain to the adult in the room, [that] you can’t do that to a kid, it’s way too damaging.”

People often ask Ross how he was able to photograph inside detention facilities. At first, he said, access was easy.

“I started going around to institutions, and I would go at least once a week,” he said. But when his photos became the catalyst for juvenile justice reform, “doors started closing in front of me,” Ross said.

In his photo series, Ross invites viewers to empathetically visualize the conditions of confinement that children endure. For advocates like Jennifer Lutz, an attorney for the Center for Children’s Law and Policy in Washington, D.C., and campaign coordinator for Stop Solitary for Kids, his images are a “game-changing tool.”

“Photographs and images from inside juvenile jails and prisons undeniably show that these youth are not frightening offenders,” Lutz said. “Instead, they are children, no different from yours or mine. These images capture the inhumane, bleak, and overly-correctional conditions inside some juvenile facilities –– places where no child should be.”

Across the country, more than one-third of children behind bars have spent time in solitary confinement, according to a report by the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia. A typical stay in isolation can range anywhere from a few hours to six months, leaving many with physical, psychological and often developmental damage.

As a photographer and professor of art at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Ross said he thinks of himself as a conduit for the voices of these incarcerated children.

“Each kid’s image and voice is compelling to me,” he said. “And it’s my job to pass it over to you, with the lightest touch possible and just let that kid tell the story.”

Ross’s photography is supported through prestigious grants from philanthropists Pam and Brook Smith, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. He also was awarded Fulbright and Guggenheim Fellowships.

The power of his images is their ability to illustrate the “inhumanity” of the justice system, said Laurie Garduque, criminal justice director of the MacArthur Foundation.

“The system causes damage and harm, and it shouldn’t be this way,” Garduque said. “Behind the images is a narrative that compels people to ask why is the system this way and how can we change it. Richard isn’t issuing a call for help but action.”

Ross said his journey documenting children in the justice system began when his book “Architecture of Authority” brought him to an ICE detention center in El Paso, Texas. It was here when he saw six detained kids in cells, with their backs turned toward him, that he realized the focus of his work was about to transform.

“I was sitting there talking to them and I was the only way they were going to have a voice,” he said. “And then it really became a mission.”

Over the course of his 15-year journey documenting America’s isolated youth, Ross’s work, lauded by advocacy groups, filmmakers, writers, academics and policymakers, has helped to push legislative reform for juvenile justice –– notably exhibiting in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, along with state and local courthouses.

For Ross, his images are not for the traditional art student, but instead for the people who are most affected.

“My ideal viewer is the kid, to make sure that they know they’re valued,” he said. “The kid that’s been released, to make sure that their experience in this world has been noticed, honored and responded to. And the people that are going to change that policy for the future.”

Laura Abrams, a University of California, Los Angeles social welfare professor, used one of Ross’s images for the cover of her 2013 book, “Compassionate Confinement: A Year in the Life of Unit C.”

“Youth imprisonment in this country is extremely diverse,” Abrams said, pointing to Ross’s collection as one that portrays the vast range of facilities.

The kinds of juvenile facilities are as varied as the kids they detain. Some are old orphanages, some transitioned from mental health facilities into juvenile holding centers or treatment centers, some are group homes and some are locked facilities, Abrams said.

“A lot of people have an image of youth imprisonment as just being in a cell, [and] that fits some facilities, but a lot look more like dormitory style,” Abrams said.

In over 35 states, Ross has captured images of hundreds of facilities and isolation rooms. His photography showcases the vast range of detention types and the architecture behind them, while drawing the viewer into the blurred and obscured faces of kids in isolation.

Seeing these graphic images can and should be shocking, Lutz said.

“Much like [how] images of the murder of George Floyd have sparked a new awareness of racial violence and oppression, images of incarcerated youth speak to our shared humanity,” Lutz said. “We cannot look away. Ross and other artists’ work is a critical driver of reform, empowering advocates to compel justice professionals, judges, legislators, and other stakeholders to confront these realities and the urgent need for change.”

Driven by conditions children in detention facilities are subjected to, Ross sees no end for this project, calling it a moral imperative.

“How do you walk away from it?” he said. “I can’t figure out how it stops unless it’s handing it off to another generation that’s going to say, ‘I’m going to make a difference, not in all these kids, but in some of them.’”

Lead source photo courtesy of Richard Ross