(Photo courtesy of Google Earth)

On a morning he should have been in middle school, 12-year-old Isaac Durham collapsed on the sidewalk after drinking a fifth of vodka stolen from a Circle K in Flagstaff, Arizona. After the paramedics pumped his stomach, he was charged with underaged consumption of alcohol and became a juvenile offender for the first time.

In the seven years that followed, Durham, a member of the Hopi Tribe, spent five years, on and off, in juvenile detention. Before he was locked up, he strategically bounced between the reservation and non-Indian land to avoid punishment – exploiting the divide between tribal and county jurisdictions.

“By the age of 19, I was a full blown meth and heroin addict, injecting meth and heroin and homeless on the streets,” Durham said. “That’s when I was at my rock bottom.”

Generations of historical trauma and increased exposure to violence make young Native Americans more vulnerable to the complicated, often contradictory clutches of the juvenile justice system, legal experts say. Once in the justice system, Native children become lost in a jurisdictional web, a dysfunctional state system and a federal system that has no proper place for them.

Isaac Palone, a member of the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe, whose desert reservation straddles the Colorado River in southern Arizona and California, shares a similar story.

Palone was born on his grandmother’s living room floor to an alcoholic mother who had taken laxatives to conceal her pregnancy. After years of abuse in both his family home and in state care, he turned to drugs and alcohol.

“By 12, I was already involved with the cops,” Palone said.

He spent his last four months as a minor on probation for burglary. Soon after he turned 18, he broke the law again and, according to the Yuma Sun, was one of the city’s most wanted criminals. Tried for three burglaries and aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, he was convicted and imprisoned for seven months.

Left: Isaac Durham, 25, lives and works at Teen Challenge in Phoenix, where he mentors young people who struggle with addiction. “I can't tell you exactly what career I want to do,” says Durham, a member of the Hopi Tribe, “but I know that I want to help Native Americans.” Right: By the time he was 12, Isaac Palone says, “I was already involved with the cops,” and as a teen, he turned to alcohol and other drugs. “The only thing I could do on my own was basically drink.” (Portraits taken remotely by Layne Dowdall / News21)

Durham and Palone live nearly 200 miles from one another, but they share strikingly similar stories, and their experience is common to Native American youth, who are three times more likely to be imprisoned than their white peers, according to the Sentencing Project.

Native young people are “almost twice as likely to be petitioned to state court for skipping school, violating liquor laws, and engaging in other behaviors that are only illegal because of their age, (often known as status offenses),” according to a 2015 brief by the Tribal Law and Policy Institute. In 2017, 752 Native American youth lived in residential placement, which includes detention centers, group homes and boot camps, according to the National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Unlike other children, Native American children can be tried and sentenced in tribal, state or federal justice systems. Once they make contact with the justice system, Native youth face unique complications that many don’t understand, said Addie Rolnick, associate professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

“It kind of makes many people throw up their hands and not want to touch the issue of Native youth,” Rolnick said.

These policies mean that the federal justice system affects Native children in unique ways, according to the Indian Law & Order Commission, created in 2010 to investigate what it called the broken justice system in Indian Country.

“Today’s American Indian and Alaska Native youth have inherited the legacy of centuries of eradication and assimilation-based policies directed at Indian people in the United States,” the commission reported.

It suggested giving jurisdictional power back to the tribes. One recommendation would give tribes the ability to opt out of federal and state jurisdiction, allowing them to determine their children’s path through a justice system closer to home.

“We recommended that the federal government just get out,” said Troy Eid, former U.S. attorney for Colorado and chairman of the Indian Law & Order Commission. “We don’t think they should even be in this business and that the tribes should have that decision.”

Eid noted, however, that none of the commission’s recommendations were taken up by Congress.

Today, some tribes are trying to reclaim authority over their children’s rehabilitation. Tribes across the country are striving to address and heal some of the issues that make Native children more susceptible to fall into the justice system.

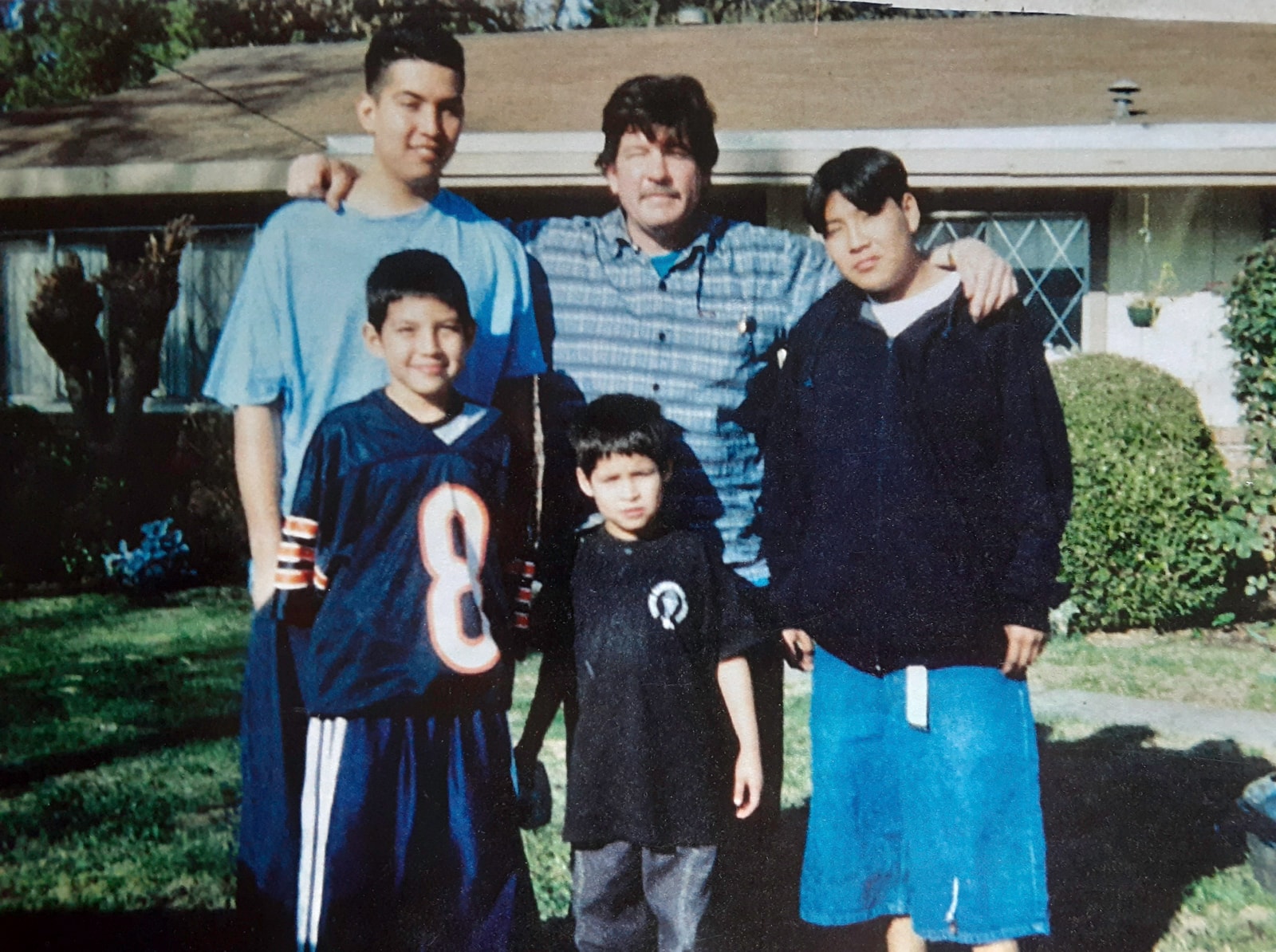

Durham, now 25, and Palone, now 23, say trauma and a lack of parental guidance were factors contributing to their substance abuse and criminal activity. Durham said his father and older brothers were alcoholics.

“That’s kind of what shaped my outlook growing up,” he said. “I just kind of fell into that mold and started drinking at a young age.”

Centuries of federal policies have undermined tribal sovereignty, according to Tribal Youth in the Juvenile Justice System, a 2016 report by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Federal control of Native youth included their forced relocation into boarding schools beginning in 1860 and continuing into the 1960s, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

The boarding school policy resulted in children being forcibly removed from their homes and taken to boarding schools far away, Eid said, to erase cultural identity and break family and tribal bonds.

“You’ve got parents and grandparents who didn’t ever really learn how to parent,” Eid said. “They had to kind of figure it out.”

Durham said both his mother and grandmother attended Native American boarding schools out of state. Experts say boarding schools, along with other policies meant to assimilate Native youth into white culture, resulted in historical trauma that still has repercussions today.

Claudette White, Palone’s aunt and former chief judge at San Manuel Band of Mission Indians in Southern California, said “historical trauma” is a misleading term because “it’s not just something that happened (in the past). It’s something that we live with and something that impacts people today.”

Isaac Palone’s aunt, Claudette White, lives on the Fort Yuma Quechan Reservation in Winter Haven, California, and has been a chief tribal judge. White believes Native youth in the justice system need a direct engagement with Indigenous culture for successful rehabilitation. “One of the things we're trying to do to the tribal court aspect is really offer education for people who are willing to change, embrace it or acknowledge it, or put them on notice if need be.” (Photo courtesy of Claudette White)

Conditioned by generations of trauma from systemic efforts to erase Native culture, Native children still experience high levels of trauma, poverty and violence today, according to a 2019 National Congress of American Indians report on juvenile justice.

These conditions make Native American children “particularly susceptible to entry into the juvenile justice system, and increase the obstacles they face to a successful and healthy reentry,” according to A Roadmap for Making Native America Safer, a 2013 report from the Indian Law & Order Commission.

Rolnick, who specializes in juvenile and criminal justice, indigenous rights and race at UNLV, said multilayered legal jurisdictions are responsible for many of the issues Native youth face in the justice system.

A Native youth can be prosecuted in three courts – tribal, state and federal. Tribal courts generally handle less serious offenses, while the federal and state systems tackle serious crimes, such as rape and murder. Unlike the government’s relationship with states, Rolnick said, a federal prosecutor needs no tribal approval before proceeding against a Native youngster.

Jurisdiction in Indian Country has been shaped by decades of Supreme Court rulings and federal policy decisions, resulting in what the Indian Law & Order Commission called an “indefensible morass of complex, conflicting, and illogical commands.”

On the majority of tribal lands, the federal government prosecutes rape and murder as well as some less-serious crimes, such as burglary and theft. Elsewhere, however, most young people are not subject to substantial federal involvement.

An estimated 13% to 19% percent of youth involved with the federal justice system were Native American, even though they account for just 1.6% of the national population under age 18, according to a 2018 Government Accountability Office report.

“But they’re there for what would otherwise not be federal offenses,” Rolnick said.

The federal system is not built for juveniles, and it’s meant to punish, not rehabilitate. Once kids are in the federal system, it lacks the diversion and parole programs state and local systems offer juveniles, the Law & Order Commission said, adding that “Native juveniles in federal custody are systematically receiving longer sentences of incarceration for the same or similar offenses.”

“It’s out of sight, out of mind,” Eid said. “There’s this whole block of Native American young people, who by accident of history, are now in federal detention. And it’s a travesty.”

Eid recalled visiting a federal detention center for juveniles where there were no school programs or resources because no budget had been requested. The pattern repeated itself across several federal detention facilities, Eid said.

“They had nothing to do,” he said. “They were just sitting there. There’s no school for them. Can you imagine?”

In 2009, Bryan Austin Boneshirt, 17, killed 19-year-old Marquita Walking Eagle on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, according to court documents. Boneshirt’s case fell under federal jurisdiction, given that he and Walking Eagle were both Native American and the crime occurred on tribal land.

Boneshirt initially was charged as a juvenile for first-degree murder, until he took a plea to transfer the case to adult court, where the charge was reduced to second-degree murder, court documents show.

Boneshirt pled guilty and was sentenced to 48 years in prison. At the time of his sentencing, the life expectancy for a Native American male was 58 years, according to his appeal. Boneshirt will be 59 when he is released in 2051, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

“The district court anticipated Boneshirt would be an old man when he was released, but in reality he may be a dead man,” the appeal said.

Eid said Boneshirt’s sentence was not bound under the sentencing restrictions for juveniles set forth in the 2010 Supreme Court case Graham v. Florida, which determined that it was cruel and unusual punishment for juveniles to be sentenced and incarcerated for their entire lives in the state system.

His sentence would have been shorter if Boneshirt had been tried in a district or state court, given that he would have had the possibility of parole and earned time, Eid said. Unfortunately, Native American children are exclusively subject to a federal system that imposes longer sentences for similar offenses.

“Because he’s Native American and he’s a juvenile, he’ll be incarcerated for the rest of his life,” Eid said.

Native youth also face challenges within state justice systems. In 1953, the federal government passed Public Law 280, which gave certain states shared criminal jurisdiction with reservations. White, a former judge for the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians and Isaac Palone’s aunt, said lack of recognition of tribal authority over time has led to gaps in communication between states and tribal governments.

Durham, the Arizona Hopi, often used those jurisdictional conflicts to his advantage. To avoid probation officers, he said, he would strategically move between Flagstaff and the reservation, nearly a two hours’ drive, where his grandmother lived and his mom was from.

Isaac Durham, front center, pictured with his father and brothers, says trauma and a lack of guidance contributed to his substance abuse and criminal activity as a child. (Photo courtesy of Isaac Durham)

Coconino County does not notify tribes when officers apprehend tribal youth for delinquency, said Lionel Scott, the county’s lead probation officer. To do so, he said, would violate the youth’s rights.

Advocates say that, based on the Indian Child Welfare Act, a 1978 law that prevents tribal children from being unlawfully removed from tribal care, states should notify tribes when youth make contact with the justice system for status offenses, such as underage drinking and running away, that only are crimes for minors. Some advocates say there should be a law modeled after it for delinquency, too.

Tribal notification can allow tribes to intervene on kids’ behalf and, ideally, divert them to alternative rehab programs close to home. But state and federal systems are inconsistent in identifying Native youth they interact with, and in notifying tribes.

States affected by Public Law 280 aren’t required to consult with tribal governments on matters related to Indian Country law enforcement. New Mexico is one of the only states that has a law specifically requiring state courts to notify and consult with tribal authorities when petitions involving Native youth are filed in state court.

Federal and state facilities are sometimes hundreds of miles from a child’s family and tribe, further separating them from their support system and culture, experts say. But even where facilities are close to home, overlapping jurisdictions can complicate matters for Native youth.

While Palone was on probation in Yuma, he wasn’t allowed to make the 10-minute drive to his aunt’s house on the reservation to see his family, because Arizona’s jurisdiction did not extend to the reservation on the California side of the Colorado.

“Literally, it was just the river dividing us,” White said. “And if he wanted to come live with family or be released to us, he would be violating probation immediately.”

Palone attributes his recidivism in part to this jurisdictional constraint, which kept him from getting help from his family when he needed it most.

Eid said the Law & Order Commission had hoped its bipartisan set of recommendations would develop congressional support, which is required because jurisdiction issues in Indian Country are in Congress’ control. So far, he said, little enthusiasm has been shown.

“There just is not any interest,” Eid said. “I can’t get anybody’s interest in it.”

Rolnick said that even if tribes don’t have the infrastructure or don’t want to take on all cases, they at least should have the choice to opt out, like states do.

“It doesn’t matter how small a tribe is, it doesn’t matter how much money they have,” said Kelbie Kennedy, policy counsel for the National Congress of American Indians. “I think all tribal nations want to have the ability to help their youth. And part of that comes with jurisdiction – to have jurisdictional choices over their youth.”

Tribal justice systems tend to be more focused on rehabilitation and restoration, which is what juvenile justice was intended to be.

“It’s ironic, of course, because now all the non-Indian courts are like, ‘Let’s do restorative justice,’” Rolnick said. “And that is what the tribes were doing – or many of them – all along.”

Palone said he had a friend from school who went through the tribal justice system instead of the state system and had a better outcome.

The Gathering of Native Americans is a culture-based program that utilizes cultural values, traditions and spiritual practices to help address issues that affect Indigenous communities across the country.

The gathering is “a journey of healing and transformation,” according to a fact sheet issued by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. “It is as much about healing the past as it is about building the future.”

“Having the opportunity to be in our own community or be with tribal family would have changed the outcome for Isaac,” White said, “because it would have kept him very grounded and connected.”

Isaac Palone, right, with Saginaw Grant, center, and the Kwatsan Lightning singers in 2015 in Yuma, Arizona. Palone says singing traditional Quechan songs helped him heal while he was in prison and after he got out. (Photo courtesy of Claudette White)

When Palone was living with his aunt on the reservation before his incarceration, he had experienced a level of healing from participating in his tribe’s traditional lightning songs. The songs helped him even in prison.

“There’s that sense where you feel lonely, like something was missing,” he recalled. “Every time I would start getting into that depressed state, I would sing songs and I felt like I was at peace.”

Palone was released in September 2017. At age 23, he’s living on the Cocopah reservation near Yuma. In June 2020, he got a job in a restaurant, and he said he has stayed sober.

White still has the voicemail her nephew left her the day he got out.

“Based on looking at his history, his trauma, early childhood traumas, the experience of his family and how functional they are or aren’t, Isaac’s doing pretty well for himself,” White said. She thinks a lot of his success comes from relying on Quechan culture and tradition.

“He seems to really embrace the things that have been taught to him,” she added.

Tribal justice systems could help more young people but, like most federally funded tribal entities, they are chronically underfunded, according to the 2019 National Congress of American Indians report on juvenile justice.

“It doesn’t matter, really, who’s president in terms of Indian Country, in terms of funding,” Eid said. “I’m confident that we are spending less on Indians per capita now than we did last administration than we did the administration before.”

Many tribal justice systems and programs are funded by short-term grants that tribes have to compete for and that may have limited uses, according to the Congress of American Indians report.

Durham said there aren’t many programs or mentorship opportunities to keep young people occupied on reservations.

“The youth that have the most successful outlook are those who are in sports,” he said, “because that’s something that actually keeps them accountable to dreaming about a future, and they have a coach that is speaking into their life and directing them and guiding them.”

Durham attributes his success after prison to becoming a Christian and the influence of his mentor, Frank James, a minister who taught cartoon drawing and led Bible studies in the Coconino County Juvenile Detention Center. James let Durham live with him for a year before Durham moved to Phoenix to enroll in Teen Challenge, a Christian rehabilitation center.

At age 25, Durham continues to live and work at Teen Challenge, where he mentors other youth struggling with addiction. He earned an associate’s degree and is working on a bachelor’s in nonprofit leadership and management with a concentration on American Indian studies at Arizona State University. He has reconciled with his father and plans to return to the Hopi Reservation to mentor the next generation of youth.

“The work I do is just a constant reminder of where I came from and I feel an obligation to do good to break the destructive cycle of my family,” he said.

José-Ignacio Castañeda Perez is an Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation fellow, and Calah Schlabach is a Buffett Foundation fellow.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.