(Photo courtesy of Ymilul Bates)

For families with incarcerated children, the burdens are overwhelming: financial, psychological and emotional. All are exacerbated by court fees and fines, travel costs and loss of employment or educational opportunities.

One in three families with imprisoned children may have to choose between buying food and court costs, according to a report by Justice for Families.

“There were definitely times where I went without eating so I could put my last $20 on his phone or commissary,” said Brandi Reals of Knoxville, Tennessee, whose son is serving a 25-year sentence in Florida. “Whatever was going to add to him feeling comfortable was more important.”

Impoverished families and families of color are disproportionately affected by these financial burdens, which can amount to an entire year’s household income, forcing some families into debt.

For half of family members, the emotional trauma causes negative health effects, including PTSD, depression and anxiety, according to the report “Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families.”

Shannon Rees of Myrtle Point, Oregon, said the first year of her daughter’s 11-year sentence for attempted homicide and assault has been the hardest thing she’s experienced.

“It’s all but broken me (but) I can’t just lay down and die,” Rees said. “I felt like that a thousand times, but your heart just keeps beating and your lungs just keep expanding, but you’re wandering the Earth with the hugest hole inside of your heart.”

Siblings of imprisoned children also are affected, although most research focuses on the parents, according to a study by Lauren MacDougall of Covenant College Shared Justice.

Reals said her 14-year-old daughter, Drew McElraft, was traumatized when her older brother, Chayse Jackson, was arrested in 2014.

“I didn’t even go to high school for my senior year because I just didn’t feel like I could handle it,” said McElraft, who’s now 20.

Luke Ryan, a public defender in Northampton, Massachusetts, said family members often feel guilty for not doing more, but many simply can’t. It’s heartbreaking to see so many parents in court who are struggling to be good parents, he said.

“They’re in a position of having to work two or three jobs, and they can’t be there when their kids get home from school and help them with their homework,” Ryan said. “A lot of parents kind of take it on themselves for their kids’ problems when you know the village is really what is falling short.”

Here’s a look at six families impacted by youth incarceration.

Nicole Hingle at her home in Chalmette, Louisiana. Hingle’s son, J.H., 18, is incarcerated at Florida Parishes Juvenile Detention Center in Covington. (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie / News21)

Nicole Hingle, 37, a single mother of two from the New Orleans area, spent the Fourth of July on a vacation in Texas with her youngest son. Looming over them was the absence of Hingle’s oldest son, J.H., 18, who will be in Louisiana’s juvenile justice system until January 2023.

“It can be very difficult and hard to just let go and have fun because of the sense of something’s missing,” she said.

Hingle, who said she tells her kids she would “live under a bridge if it meant helping them,” calls J.H.’s incarceration “the worst experience of my life.”

Although he was sentenced just last year, J.H. — who has severe attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, which makes him impulsive — has been involved in a riot and several fights, broken his jaw, talked about suicide and been exposed to excruciating isolation, she said.

When a judge denied J.H. the opportunity to participate in Youth Challenge – a rehabilitative program that could have helped him earn early release – Hingle said she lost faith in the system and committed herself to understanding its flaws. She spent days on end in the library researching juvenile justice, her son’s case and the developing brains of adolescents. In the process, she lost her job, home and car.

“I felt that I had to save him from the system,” Hingle said. “Everything around me just fell apart.”

Renée Slajda, communications director for the advocacy group Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, said J.H.’s facility is one of two in the state that are severely outdated and originally built to house adults.

In April, a riot broke out in his detention center. Hingle said J.H. called her in the midst of it, with a shirt over his face because pepper spray filled the air.

COVID-19 has exacerbated the problems she sees. Since March, she said, not only have in-person visits been canceled, so have school and other rehabilitative programs.

“That’s why you see things like the so-called riot,” Slajda said. “Imagine a room full of 15-year-old boys together for 23 hours a day with literally nothing to do.”

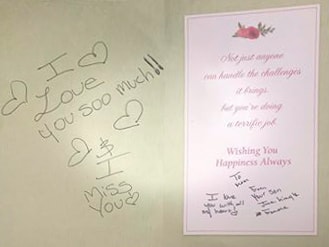

A birthday card J.H. sent his mother, Nicole Hingle, from Florida Parishes Juvenile Detention Center. (Photo courtesy of Nicole Hingle)

In recent months, Hingle has only seen her son sporadically via video calls. He hasn’t shaved or had a haircut since the pandemic, she said.

“My child looks like he’s lived in a jungle for the last five months,” she said.

Hingle said she tries to encourage him to practice non-violent conflict resolution, but J.H. tells her the peaceful approach isn’t practical.

“You have to understand, if you don’t fight, you become the target,” Hingle remembers her son telling her.

Hingle is fighting in her own way. She plans to attend community college in the fall and eventually start a rehabilitative program that helps kids before they get in trouble.

“When they go to jail, we’re throwing them away,” she said.

Hingle also is fighting to gain political power to change things for her son and children like him.

“I am not a doctor, I am not an attorney,” she said. “I know what I’m talking about because I’m a mom.”

Drew McElraft, 20, and her brother, Seth Jackson, 25, at their mother's home in Knoxville, Tennessee. Their brother, Chayse Jackson, 18, is incarcerated in Florida State Prison in Raiford. (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie / News21)

Drew McElraft and her mother were at a circus in Knoxville in 2014 when her mother got the phone call about her 17-year-old brother, Chayse Jackson, that changed everything.

“We were supposed to spend the rest of the day together. She just took me home and I could tell something really bad happened,” said McElraft, who was 14 at the time. “When we pulled out, she told me that he had been arrested.”

Jackson, who is autistic, had been arrested in Florida for a sex crime. He later was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in an adult prison.

Soon after his arrest, McElraft felt the emotional toll. She began drinking, failing classes — and eventually attempted suicide. She worried about her brother, “an unwell, autistic, confused child” locked behind bars.

“I just imagined him being scared. It’s been hard just knowing that he’s had to grow up in a prison,” she said.

McElraft also worries about her mother, Brandi Reals, who is suffering emotionally and financially after her son’s arrest.

“I couldn’t get out of bed for two or three weeks,” Reals recalled. “I didn’t eat, I didn’t really do anything. I didn’t have a job. I just couldn’t move. It was completely disabling. And I knew I had no ability to help him with a lawyer, or go down there … the powerlessness of that.”

Brandi Reals in her kitchen in Knoxville, Tennessee. Reals’ youngest son, Chayse Jackson, is incarcerated in Florida. “I didn’t have a job at the time. I was at the lowest place in my life already, so that was a big kicker,” Reals says. “There was just nothing I could do, not financially.” (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie / News21)

A 2018 study by the National Center for Biotechnology Information found that families feel powerlessness because communication and information often are limited. Reals, like McElraft, is concerned about her son’s high-functioning autism.

“It was just heartbreaking to hear him try to make sense out of it all,” Reals said. “Even though he was 17 and still a child, mentally he was very much 12 or 13.”

The financial pain is just as real. Each trip from Tennessee to Florida costs about $400.

“To go down and see him, it’s gas, it’s time away from…making money,” Reals said.

McElraft said she worries her mother won’t be able to care for Jackson when he gets out of prison in two decades.

“My brother will never be the same if he survives his sentence, and it’s going to be rough regardless,” she said. “If he does survive it, my mom’s going to be a 70-year-old woman who’s going to have to devote the rest of her life — if she’s well or makes it to 70 — to a child.”

Kevin Alderman reminisces about his nephew, Tristin Alderman, who was incarcerated several times as a juvenile and later convicted of murder and robbery and sentenced to life in prison. (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie / News21)

Kevin Alderman of St. Louis paused before reminiscing about his nephew, Tristin Alderman, who was incarcerated for the first time at age 14, when he broke into a police officer’s home in Davenport, Iowa.

“I remember one time he came out with my mom to visit us and he got to ride a dirt bike for the first time,” Alderman recalled. The 10-year-old “could not believe that you can have this much fun.”

Tristin, now 23, was incarcerated several more times during his youth and now is serving a life sentence for robbery and murder.

“He needed a positive influence in his life,” Alderman said.

Left: Tristin Alderman, left, poses with a cousin. Tristin, now 23, is in prison for life. Right: Tristin, right, with his cousin, Kevin Alderman’s son. “At least I know that when he hung out with us, he got to be a kid,” Kevin Alderman of St. Louis says of his nephew. (Photos courtesy of Kevin Alderman)

Tristin’s father, a member of a biker gang, was sentenced to 16 years in federal prison during Tristin’s childhood, Alderman said. Tristin became involved in gangs and criminal activity at an early age, and his uncle still struggles with guilt from not doing more to keep him in school and out of prison.

“All I wanted to do was give him a chance,” Alderman said. “I think I could make a difference, I really do.”

Having a child in the justice system changes people, he said, and provokes disagreements within families that never seemed possible.

“The family literally imploded because of things that were going on,” Alderman said. “It’s sad. It tears families apart.”

Alderman pays for his nephew’s phone and email privileges in prison. He just ordered him a book on bodybuilding, warning Tristan, who has transferred prisons three times because of gang fights, not to use it “to beat anybody up.”

Alderman, who works for an airline, made it his goal to take his nephew on an annual trip with his cousins so Tristin could spend time with Alderman’s kids and have some semblance of a childhood. But as he grew up, Tristin either didn’t want to go or was in too much legal trouble to leave Iowa.

Alderman said he once took Tristin to visit his father in prison, hoping to scare him into changing the course of his life.

Nothing helped.

“My mom and dad are doing backflips in their graves at Mount Calvary Cemetery over what has happened,” Alderman said. “He’s never been able to be a kid. That’s what really bothered me.”

Ymilul Bates, in her home in the San Francisco Bay area, has paid thousands of dollars since her son, Azrael Vargas, was charged with theft last fall. (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie / News21)

Ymilul Bates woke up to a phone call at 3:30 one morning last fall. The automated message said the call was from a jail. Thinking it was a wrong number, she hung up.

“Then I got a call again and it was my child’s voice,” Bates said. “I was standing up at that point, and when I realized it was him, I physically collapsed.”

Bates was working toward a master’s degree in social work and living with her sister in Tucson, Arizona, at the time. Her son, Azrael Vargas, 19, had been arrested for theft in the Bay Area and, if convicted, faced up to 39 years in an adult prison.

His bail was set at $500,000. Bates said she pulled from her teacher’s retirement to pay $45,000 up front and also hired a lawyer for $30,000. She also pays for her son’s ankle monitor.

“At this point, I just stopped keeping track of how much I’ve paid,” Bates said.

Bates moved back to California to be near her son. Because of COVID-19, his trial date is uncertain, but she plans to move close to the facility where he’s sentenced. She also has made sure that Vargas continues his college classes and therapy.

When Vargas was 14, his best friend was murdered; Bates believes her son’s actions stemmed from this unresolved trauma.

“I just want him to be in a better place, emotionally and spiritually, before facing the consequences,” she said.

Bates is looking for correspondence courses so Azrael can finish his degree in prison. Although finding a family support network for herself is on her to-do list, Bates hasn’t gotten around to it, so she writes instead.

In January, Bates contributed her essay, “I Wonder If They Know My Son Is Loved,” to the Marshall Project, a news site that reports on justice issues.

Left: One of Azrael Vargas’ childhood drawings. Right: Azrael Vargas and his mother, Ymilul Bates. In an essay she contributed to The Marshall Project, “I Wonder If They Know My Son Is Loved,” Bates writes, “I feel his pain with motherly perception, disemboweled by the realization that, for once, I cannot protect him because, although he is still too young to drink and nearly too young to vote, the criminal justice system regards him as an adult.” (Photos courtesy of Ymilul Bates)

“I see him through motherly eyes — a well-intentioned, gentle-natured teen who got caught up in the moment and, with the impaired impulse control of a 19-year-old brain, committed an act he already regrets,” Bates wrote. “I hear him with motherly ears — the raspy, gasping voice begging for the forgiveness that I’ve already given him. I feel his pain with motherly perception, disemboweled by the realization that, for once, I cannot protect him because, although he is still too young to drink and nearly too young to vote, the criminal justice system regards him as an adult.”

Bates has not questioned her sacrifices, but she fears how Azrael will handle an adult prison without her.

“He and I are so close; it’s just been the two of us since he was about 5,” Bates said. “Just feeling like you’ve thrown your child to the sharks and you’re waiting from the water’s edge.”

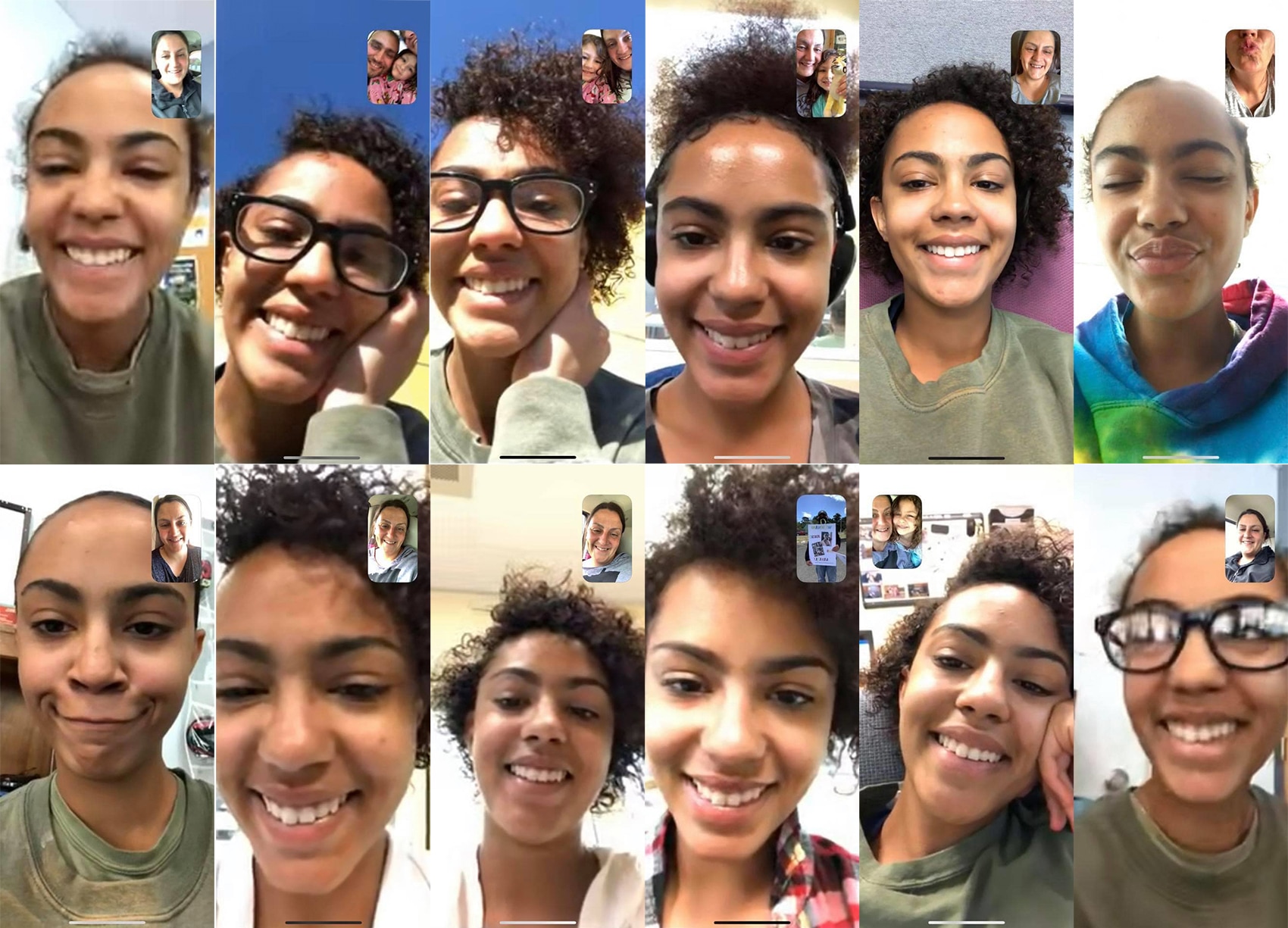

Shannon Rees and her daughter, Saraya, FaceTime twice a week while Saraya is incarcerated in Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility in Albany, Oregon. (Photos courtesy of Shannon Rees)

Shannon Rees keeps a photo from Christmas 2019 in her car, a reminder of the best day in “a really rough year” that saw her daughter begin serving an 11-year sentence for two counts of attempted homicide and one count of attempted assault.

“This was the first time that they let the girls see each other at the prison, right before Christmas,” Rees said. “That was like the happiest day.”

Up until last year, Rees lived on a dairy farm in Myrtle Point, Oregon, population 3,000, with her husband and daughters, Saraya, 14, and Pyper, 4.

But since July 2019, Saraya has been at Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility.

“They didn’t take into any account at all her mental illness, her previous history, and the biggest problem I’ve noticed with her mental illness is that she’s so young, even the professionals don’t want to diagnose her,” Rees said.

Doctors have used such terms as major depressive disorder and social anxiety to describe Saraya, but Rees said her daughter has been suicidal from a young age, struggling with bullying and forging friendships.

“We told every person involved in this that this was a mental health issue,” Rees said. “This is not a crime. This is a mental health issue. And they wouldn’t listen to us.”

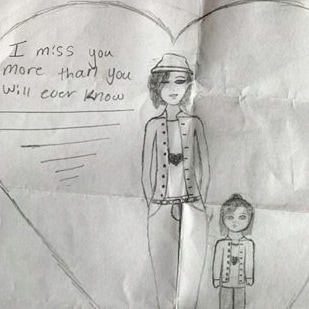

Fourteen-year old Saraya Rees, who is serving 11 years at Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility in Albany, Oregon, drew this portrait of her and her younger sister, Pyper. “She’s super into anime, which I don’t understand at all,” says her mother, Shannon Reese. “I can’t tell you how many I’ve watched since she’s been gone because I miss her.” (Photo courtesy of Shannon Rees)

Rees also struggles to pick up the pieces for her 4-year-old, who cries for her sister to come home. Because of COVID-19, Rees has not seen Saraya since March 13, and Pyper has not seen her big sister since Christmas.

“Mom is such a powerful word, right? But it doesn’t mean a damn thing when your kid is in the system,” Rees said. “It doesn’t mean anything at all. We’re just another person that gets left hanging with no answers.”

Rees has been sharing her daughter’s story with anyone who will listen, hoping to enact systemic change for children with mental health problems.

“It’s everywhere; it’s not just Saraya, and it’s not just Oregon. This is happening all over the place,” Rees said.

“And then Kelsey Darragh happens.”

Darragh, a Los Angeles filmmaker, comedian and mental health advocate, said she and Rees became friends after Darragh reached out on Facebook after seeing her story. Darragh has been sharing the Rees family story with her large social media following.

“This is every mother’s worst nightmare, and I think the way that Shannon has handled it is with such grace and vigor,” Darragh said. “Through this journey, I think that’s really proven what a mother is and can do.”

Even so, Rees said she routinely fights her own anger and depression.

“I go to the dollar store and I buy plates, like 10 at a time, and I’ll stand outside and just smash them because it makes me feel better to break something and then clean it up,” she said.

Rees also said she found “an impromptu support group” of mothers of incarcerated children and is sharing her daughter’s platform to amplify their stories, too.

Once her daughter is free again, Rees plans to leave Oregon to find a community where her daughter can get more support, where Saraya can thrive creatively and continue working on her art, music and writing.

“She’s been working on a book about a fallen angel,” Rees said. “Which is like herself, a fallen angel. She’s going to get her wings back. We’re not going to stop fighting for her.”

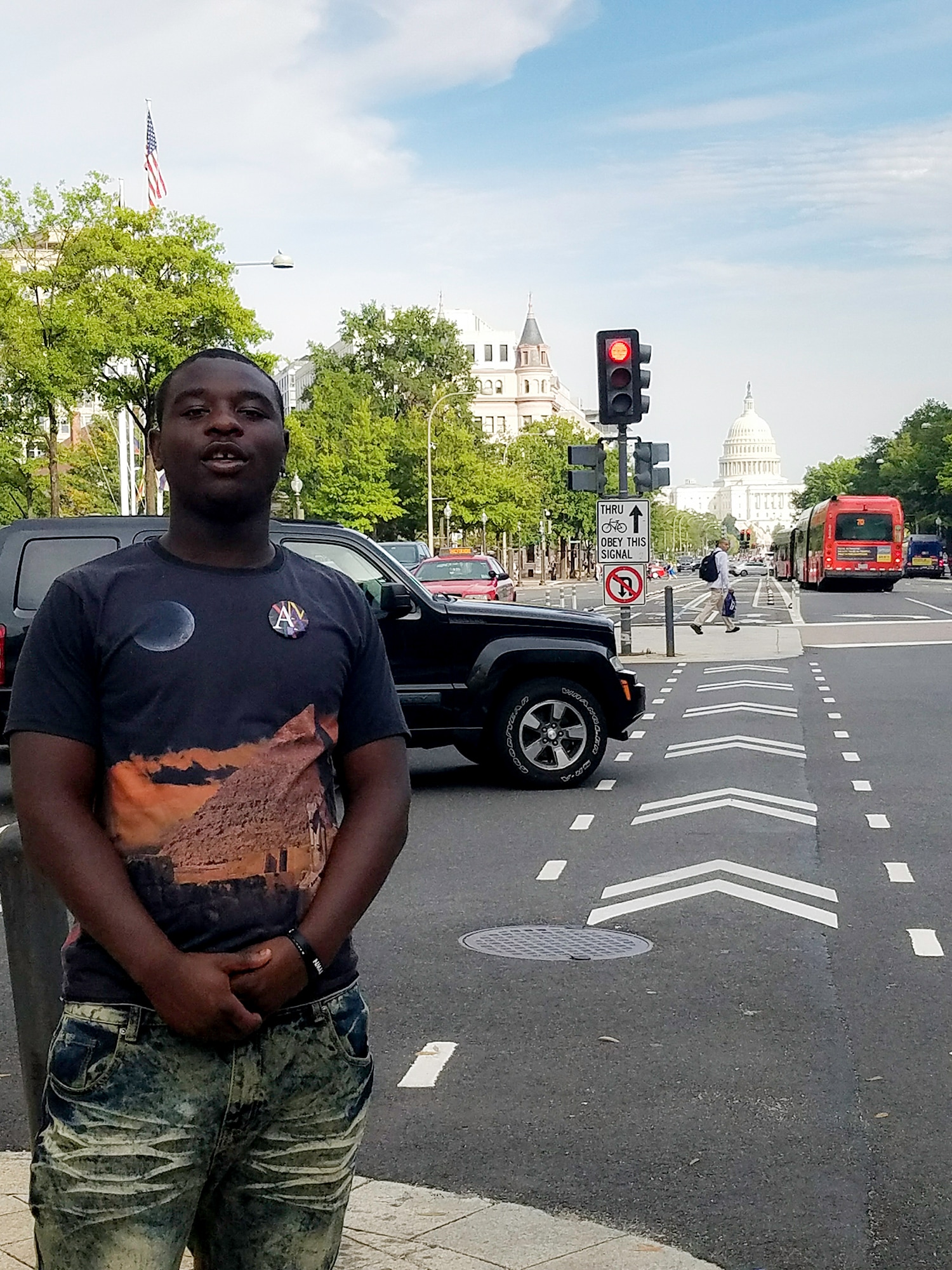

Andre Hollis with his mentor and advocate, Maria Scott of Youth Advocate Programs Inc., a nonprofit that helps young offenders and their families navigate the justice system and reintegrate into society. (Photo courtesy of Maria Scott)

June Hollis of Bear, Delaware, knew her son, Andre, had behavioral and learning difficulties from a very young age.

“He’s a very lovable, interactive child that likes having fun,” Hollis said. “He puts a smile on everybody’s face wherever he goes.”

At 17, Andre said he was arrested for holding a gun during a fight, though he said he didn’t have one.

Andre’s public defender told Hollis her son had two options: go to trial and risk 10 years in prison or take a 10-month plea deal.

“I couldn’t afford a lawyer. I’m a single mom,” she said. “So I said, ‘OK, we’ll take the 10 months in a detention center.’”

Hollis’ life improved when Youth Advocate Programs Inc., a nonprofit with locations nationwide, got involved. The organization helps young offenders and their families navigate the justice system and reintegrate into society.

Jeff Fleischer, CEO of Youth Advocate Programs, noted that public defenders, whose caseloads are large, spend only a few minutes with a young person right before a young person’s hearing.

“So you have young people scared,” he said. “You have families that may be afraid of losing their jobs, so they don’t go to court.”

The Delaware YAP office proved to be the support system Hollis needed, providing transportation to visit her son, who’s detained 45 minutes from her home, helping her find a job and suggesting support groups for moms.

“I could speak to someone when I was going through things that I couldn’t share with him because I didn’t want him to feel bad or feel down,” Hollis said.

Fleischer said his group’s 40-year-old model is an alternative to incarceration, striving to reinvest resources in the family to ensure their needs are met first.

A photo of Andre Hollis of Delaware, who was 17 when he was incarcerated for 10 months after taking a plea deal on a gun charge. (Photo courtesy of Maria Scott)

Maria Scott, a youth advocate with YAP, worked with Andre during his sentencing, providing emotional support, money for phone calls and other assistance.

“I called Miss Maria every time I needed her,” Andre said. “She ran right down as soon as I called her.”

After Andre finished his sentence, YAP helped him reenter the community and find a job.

Hollis, a single mother, also appreciates the way the group provides positive male role models.

“It’s that missing link with his father not being there – that he has another resource and another outlet he can call on,” Hollis said.

Jos Fox is a Myrta J. Pulliam fellow, and Anthony J. Wallace is a Donald W. Reynolds Foundation fellow.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.