(Document courtesy of Charles Bonner)

School environments that rely on harsh punishments to control classrooms often leave children with learning and behavioral disabilities more likely to be suspended, fall behind in school and enter the juvenile justice system.

Although they made up less than 13% of all public school students in the 2015-16 school year, according to the most recent data available, kids with learning and behavioral disabilities were arrested nearly three times more often than students without such challenges. They made up 71% of students who are physically restrained in schools, and up to 85% of youth in juvenile detention centers, according to a 2015 report by the National Council on Disabilities.

“It’s like kids with disabilities are hit twice as hard,” said Heather Griller Clark, a researcher at Arizona State University and former special education teacher in juvenile corrections centers.

In addition to facing academic challenges, struggling with how to process emotions or stand up for their own interests can leave these vulnerable students more likely to fall through the system’s cracks, said Clark, whose work has mostly focused on youth with behavioral and emotional disorders.

“In some ways, kids are pushed out, and in other ways, kids self-select to stay out,” she said.

Race, trauma and poverty also contribute to disabled children landing in juvenile detention centers.

For Jabari Boykins of Syracuse, New York, and Malachi Simmons of Greensboro, North Carolina, those factors added up.

Jabari Boykins, pictured at 13, has bipolar disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. When he was 14, Boykins suffered a broken arm and a split lip when he was assaulted by a school resource officer at his high school in Syracuse, New York. He was charged with criminal trespass and resisting arrest, but the charges later were dropped. (Photo courtesy of Liza Acquah)

When Boykins was 3, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and placed in an early intervention school. In his 18 years, he’s been physically restrained by teachers, assaulted by a police officer, arrested multiple times and placed in a group home more than 200 miles away from his family, according to court documents and Boykins’ mother.

Simmons was taken from his home at age 8 and sent to foster care after living with poverty, neglect and domestic violence. He was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and other conditions that can cause impulsive behavior, according to a lawsuit filed on his behalf.

The overrepresentation of such kids as Boykins and Simmons in juvenile detention centers is no coincidence, said Daniel Losen, director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA. The center’s 2018 analysis of nationwide data suggests that students with disabilities are being punished for behaviors associated with those disabilities.

“Students with disabilities are oftentimes unable to signal to teachers, police officers and other authority figures in a way that’s acceptable to social norms,” said M. Alex Evans, an attorney with Disability Rights North Carolina. “When they’re unable to communicate or respond in those ways, then they’re criminalized.”

Steven Nelson, a professor in educational leadership at the University of Memphis, described three ways students with disabilities are excluded from public schools.

Pushout, the first method, manifests in forms of discipline such as suspension and expulsions, he said. Shutout describes systemic measures administrators take to keep students out of school. Snatchout, which Nelson called the most pernicious form, refers to contact with law enforcement.

A one-size-fits-all model of education often pushes students who do not fit that mold out of class and into jail cells. Advocates suggest that this practice denies students with disabilities their civil right to a free and appropriate public education, despite federal protections outlined in the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act, which was signed into law in 1975.

U.S. Department of Education data from the 2015-16 school year shows that students with disabilities were suspended from schools about twice as often as students without them.

Students with disabilities are legally entitled to individualized education plans, or IEPs, which deliver a more personalized learning experience and may include such services as occupational therapy, physical therapy and mental health support.

Losen said that when a student with a learning or behavioral disability is suspended, the effect is inherently unequal.

“They’re going to lose a lot more than a kid who doesn’t get all those extra services while in school,” he said.

A News21 analysis identified 745 schools in which the average suspension length is less than two weeks for all students, but longer than two weeks for students with disabilities. At Raleigh Egypt High School in Memphis, Tennessee, students with disabilities were suspended about 35 times longer than their nondisabled peers.

The disconnect between students with disabilities and underprepared teachers hits Black students even harder. For decades, scholars have identified an equity problem with Black children in special education.

Some experts say that the tendency to label or view them as inherently defiant or dangerous causes Black youth to be too readily diagnosed with learning or behavioral disabilities.

“They are being classified as defiant, and they are going to be pushed out of the general education assignments,” said Andrew Hairston, director of nonprofit Texas Appleseed’s School-to-Prison Pipeline Project.

Others say that racial bias causes some teachers to write off Black students, not referring them to special education when they need help.

“So many kids have gone through the cracks because we just push them on and just label them as bad kids when that kid needed something extra that no one ever provided,” said Karmel Willis, an attorney with Disability Rights Texas.

Because of these biases, racial disparities present themselves in school suspension data, according to a 2018 report by the Center for Civil Rights Remedies. In the 2015-16 school year, Black students with disabilities lost 78 more days of instruction than their white peers.

By law, once a child has been suspended for more than 10 days in a single school year, there must be a review to determine whether it was caused by their disability. Such children also must be able to access the services listed in their IEP after 10 days.

A 2018 lawsuit filed by Legal Aid of North Carolina against Wake County Public School System alleges that this rarely happens. Because of appointment delays, a rule requiring a timely review is “violated all of the time,” said Jennifer Story, a supervising attorney on the lawsuit.

The lawsuit claims that by the time services are provided, damage has already been done.

“It’s easier to then push students out that way. If a student is viewed as more difficult to actually teach, then you want them out of the school building,” said Nelson, who represented students with disabilities in Mississippi, as an education advocate for the Southern Poverty Law Center.

In 2010, the Southern Poverty Law Center sued New Orleans public schools on behalf of about 4,500 students who the center claimed were being “unlawfully excluded from educational programs.”

Nelson said many of the students he encountered were labeled as truants because they “didn’t have a school.”

But the center found that many schools – often charter schools – were denying enrollment to students with disabilities, saying they didn’t serve those types of students.

Students with special education needs have been similarly shut out of schools across the country, advocates say.

For more than 10 years in Texas, there was a cap on the percentage of students receiving special education to 8.5% of a school’s enrollment or less. The national average of special education students in public schools is about 14%.

Willis said if students are denied special education services, it’s human nature for them to act out.

“It appears it’s a behavioral issue only, but it’s deeper than that because the child isn’t getting everything that they should be getting within the school day,” she said.

When Jabari Boykins was about 9, said his mother, Liza Acquah, she walked into his alternative school in Syracuse to find a teacher physically restraining him. Another time, she said, Jabari was held alone in the locker room while a security guard stood outside the door.

Jabari Boykins, 18, pictured with his mother, Liza Acquah. (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska)

Kim Sanders, executive vice president of Grafton Integrated Health Systems, was part of an initiative created to minimize physical restraints in schools. Their overuse contributes to a punitive learning environment. She said it affects the students who are restrained but also teachers, who often are injured in the process.

Sanders said it’s important to create a comfortable environment, and not one where teachers and staff are constantly trying to control students.

Advocates say an overly punitive treatment of disabled students is embedded in U.S. schools.

“It is the entire cultural philosophy, this idea that especially Black children, but also LGBTQ young people and kids with disabilities, need to be controlled,” said Hairston of Texas Appleseed. “(That) they need to be just put into these tight punitive learning environments where there is little opportunity for free expression and creative outlets.”

Boykins was 14 when he was suspended, assaulted and arrested in 2017 for not attending his first period class and refusing to leave Nottingham High School in Syracuse, according to a lawsuit filed on his behalf.

After missing the city bus, in about 17-degree weather, Boykins returned to campus and was confronted by Assistant Principal Kenneth Baxter and then by the school’s resource officer, Vallon Smith, and another police officer.

In school security video, Boykins can be seen walking with his hands in his pockets before Smith tackled him to the ground, though Smith’s written account contradicts what’s shown in the video. The officers broke Boykins’ left arm and split his lip, according to medical records and the lawsuit.

Boykins faced charges of criminal trespassing and resisting arrest, which were later dropped.

Acquah said Nottingham High does not always follow her son’s individual learning plan or use its built-in support system when he has a problem.

“They did not call any of his contact people. They did not follow his (behavior intervention) plan,” she said. “They wanted him to go out in the cold and catch a bus that had already left.”

In the wake of the May 25 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, efforts in several cities to remove sworn police officers from schools have expanded. Advocates say school resource officers, who originally were meant to protect schools from outside threats, escalate situations that usually are matters of school discipline, which leads to more arrests.

The Advancement Project, an advocacy group in Washington, D.C., documented 62 assaults by school resources officers from 2009 to 2019. Maria Fernandez, the group’s senior campaign strategist, said she noticed an overrepresentation of children with disabilities in the cases they tracked.

When police are called in, Fernandez said, they often have no information about the child’s history and lack the proper training to handle mental health crises or behavioral issues associated with disabilities.

These incidents typically are minor authority or behavior issues, said Carolyn Fink, a University of Maryland professor whose research has focused on special and correctional education.

“When you militarize it, it escalates,” she said. “It’s undeniable that the criminalization of misbehavior is a factor in juvenile justice.”

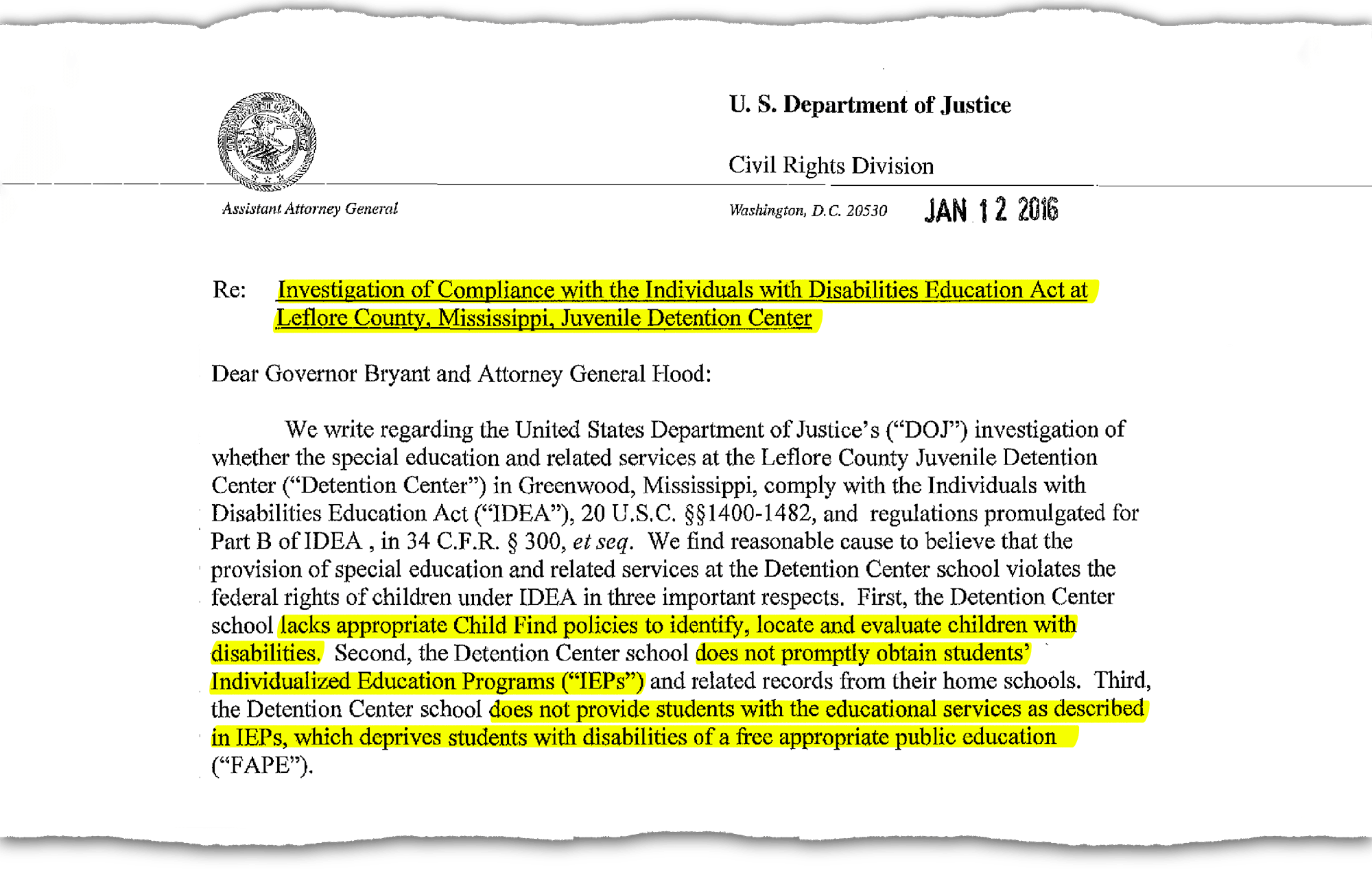

Recent federal investigations of certain juvenile detention facilities across the U.S., some of them ongoing, have concluded that the special education offered to incarcerated youth is dismal, if it’s even offered at all.

“They get differential treatment even on the way into the system,” Fink said. “Then within the system, they tend to be more often punished.”

Findings from federal investigations conducted by the Justice Department include detention centers failing to promptly obtain students’ IEPs, placing students with disabilities in solitary confinement and discontinuing their special education, according to official documents.

The National Disability Council reports that only 37% of incarcerated youth receive special education services in juvenile facilities.

This lack of support continues, even when they are placed in adult prisons.

Malachi Simmons of Greensboro was incarcerated in an adult detention center for eight months. He said he did not receive any special education in prison, despite his needs.

“The person would come in and give me work and tell me they’d be back a certain day,” Simmons said, adding that he never did the work because he didn’t know how.

Improving that situation first requires fixing public perceptions of these students, said Taryn VanderPyl, a criminal justice professor at Western Oregon University whose work focuses on youth with learning disabilities in the juvenile justice system.

“We’re talking about nonvisible disabilities so people don’t necessarily know this kid has a learning disability or ADHD or an emotional behavioral disorder,” she said. “They just see how the kid responds, and people don’t always recognize that as a manifestation of the disability, not as a bad attitude or danger.”

Beckett Haight, back center, pictured with his T-ball team in the late 1980s in San Jose, California. Haight was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder at a young age, but now he’s a special education teacher. He says he advocates for his students “partly because I felt like I didn’t have advocates growing up.” (Photo courtesy of Beckett Haight)

As a child, Beckett Haight of San Jose, California, said he never imagined himself as a teacher when he grew up. He never thought much about his future at all.

“You know, people say, ‘Well what did you want to be when you were a kid?’” said Haight, now 38. “I didn’t really think about it. I might have been like, ‘Oh, baseball player,’ but I didn’t think about it; like, I wasn’t playing baseball. I was smoking weed and smoking opium and doing whatever.”

Haight at a young age was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. These problems, coupled with the lack of resources at home and in school and his feelings of confusion, led Haight to dabble in alcohol and other drugs – and then in crime.

Haight’s introduction to the juvenile justice system came in the sixth grade when police were called after he pulled a knife on someone at a school basketball game when they refused to return a ball he had been playing with.

The incident led to him being arrested and kicked out of school. Following a few stints in juvenile hall and on probation, Haight went to drug rehab when he was in 10th grade. He left sober, on medication to treat his disabilities, and possessing what he described as a “new outlook.”

Haight has worked as a special education teacher for 15 years in schools ranging from Los Angeles to Bali, Indonesia. He said the path to the justice system for many students he has worked with results from not fully comprehending – or receiving guidance to help them understand – the repercussions of their actions.

“A lot of kids with special needs in my experience have difficulty with the higher-level thinking, and they need support from us to hit those standards and do well in school,” Haight said.

Beckett Haight, 38, has worked as a special education teacher for 15 years, supporting students in classrooms across the globe. When talking with students about his struggles with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, he says he usually notices “a good difference and a connection.” (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska)

Adjusting to life after incarceration presents other major challenges for kids with disabilities.

Sudden inaccessibility to the special education and other services they had when behind bars adds to “the barriers and stigma that youths with learning disabilities must overcome if they go back to school,” one federally cited study states.

Being set back academically, inadequate instruction and not enough guidance and services inside detention centers and back at home or school can increase their likelihood of recidivism, experts say.

Upon release, children usually are assigned a parole or probation officer, ASU researcher Griller Clark said, but those officers usually only are interested in whether the conditions of release are being met – not in whether the child learns or completes school.

Students maneuvering the reenrollment process aren’t always met with cooperation from education officials, said Sarah Beebe, an attorney with Disability Rights Texas who oversees a partnership with Harris County Juvenile Probation Department to alleviate these difficulties. Some school districts put up such “artificial barriers,” she said, such as refusing to accept students because they’re “too old” to be in the grade they need next, or refusing to enroll students without inaccessible report cards or transcripts.

Simmons said he’d dreamed of going to college and playing football. Instead, after difficulties getting back into a regular public school, he was enrolled in an alternative school, where he graduated this year. The school does not have a football team.

“I lost over a year of my life and education,” he said in a public statement.

Daja E. Henry is a Donald W. Reynolds Foundation fellow, and Kimberly Rapanut is a Buffett Foundation fellow.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.