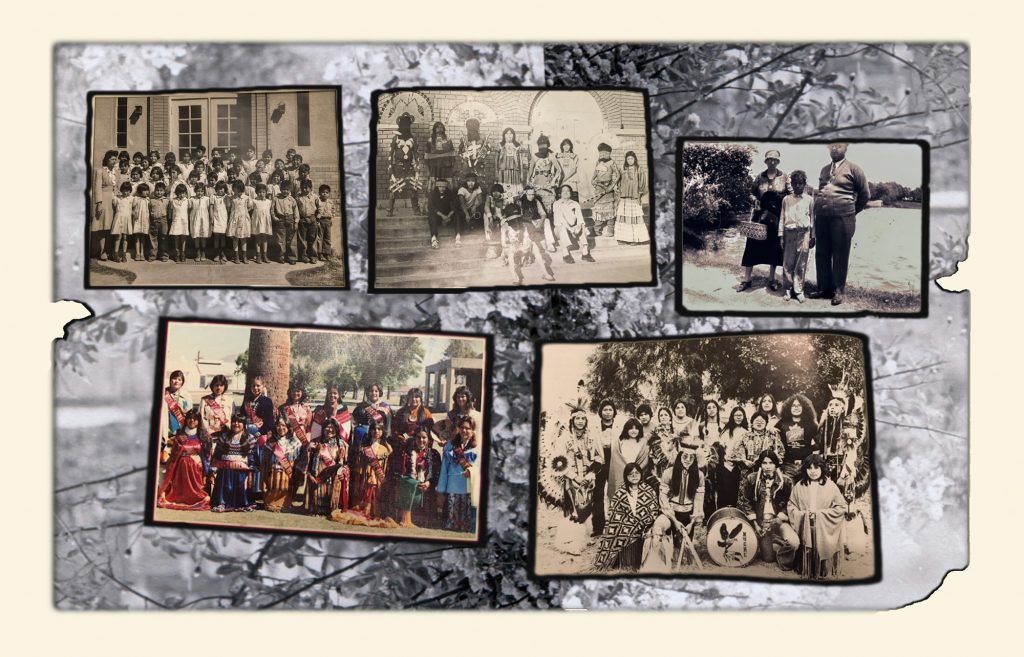

Photo illustration by Michele Abercrombie

In the early 1930s, Robert Carr, a member of the Creek Nation, was expelled for “incorrigible behavior” from Chilocco Indian Agricultural School near the Kansas-Oklahoma border.

By the time he was 21, Carr had been incarcerated in three different institutions. He died in a Kansas state prison where he was held for stealing $30 worth of food, said his niece, K. Tsianina Lomawaima, a professor and Indigenous studies scholar at Arizona State University.

It was the height of the Great Depression and, according to Lomawaima, Carr said he committed the crime because he couldn’t get a job and was hungry.

The school-to-prison pipeline –– a trend of school discipline pushing children into prison –– is recognized to have started developing at the end of the 20th century, experts say. But Carr’s story is an example of this phenomenon from decades earlier, when the U.S. government sanctioned, and sometimes operated and financed, hundreds of boarding schools for Native American children that relied on military and carceral practices to forcibly assimilate them into Western culture.

Modern juvenile incarceration disproportionately affects Native American youth, and experts on U.S. Indian policy trace the disparity back to the U.S.’s Native American assimilation policies of the 19th and 20th centuries –– which included boarding schools. Not only were boarding schools often little better than prisons, they intentionally broke up Native American families and triggered trauma that has compounded over generations, leading to many of the disparities Native Americans face today, according to a report by the National Congress of American Indians.

However, Lomawaima said the history of boarding schools is nuanced.

Native American boarding school students report vastly different experiences, many of which are displayed in Phoenix’s Heard Museum exhibit “Away from Home,” which shows the evolution of boarding schools. Early boarding schools tried to strip youth of their culture and language, but schools changed policies over time and in their final years were more culturally tolerant. Some allowed kids to remake their school policies so they could express and share their culture.

Boarding school policies were just one part of the government’s efforts to undermine Native Americans’ sovereignty and rights, Lomawaima said. These institutions were built on centuries of federal policies aimed at land acquisition through erasing Native culture.

“It’s not that what happened in boarding schools was directly responsible for every bad thing that happened in Indian country,” Lomawaima said. “But it’s linked to every bad thing that happened in Indian country.”

Lomawaima first learned about boarding school history from her father, Curtis Carr, Robert’s brother. Curtis and Robert entered Chilocco in 1927, when Curtis was 9 years old. He persevered longer than Robert, but ran away at about age 14 because he wanted to see his mom and “he just couldn’t hack it anymore,” Lomawaima said.

Lomawaima’s father rode the rails to California and weathered the Great Depression in a hobo camp, fought in World War II and eventually became a flight engineer and in-flight photographer for Boeing.

Lomawaima said the stories he told of his boarding school days were mainly lighthearted tales of boyhood pranks on teachers and his school gang teaching him to fish. Under the surface, she knew there was more.

“Even in the funny stories, you could see the reality of institutional life,” she said.

For nearly a century, the federal government funded boarding schools both on and off reservations. They were started as an extension of government policies aimed at assimilating tribes into Western culture, converting them to Christianity and weakening their cultural and family ties.

The real goal of these accumulated policies, said Addie Rolnick, professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, was to “get rid of [Native Americans] as a barrier to settlement,” enabling U.S. settlers to expand west and take advantage of the continent’s rich land and resources.

Over the years, boarding schools took many forms and Native American students’ experiences varied greatly, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, schools were brutal by many accounts.

Sandy White Hawk, president of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said boarding school survivors have given consistent accounts of abuse, forced labor, inhumane conditions and attempts to erase Native American culture by cutting students’ hair, dressing them in uniforms and punishing them for speaking their tribal languages.

White Hawk said she attended a healing ceremony for boarding school survivors where “I don’t know if there was one man who did not share that he had been raped –– and women as well.”

The education was rudimentary and largely focused on training Native students for menial labor, said former Colorado U.S. Attorney Troy Eid, who was also chairman of the Indian Law and Order Commission. Many students were forcibly removed from their homes to attend boarding schools against their parents’ wishes. In 1894, the U.S. imprisoned a group of Hopi men in Alcatraz for resisting their children’s removal.

A 1928 government-commissioned survey, now known as the Meriam Report, gave a scathing summary of school conditions, and by the 1930s, the U.S. adjusted its boarding school policies.

But, Lomawaima said, “There’s policy and then there’s practice and they don’t always line up.” Accounts of boarding school conditions during this time vary greatly.

The Great Depression was particularly hard on Native American tribes, Lomawaima said, and some parents willingly sent their children to boarding schools. They knew that at school their children would at least receive three meals a day, something many parents couldn’t provide.

This was the case for the Carr brothers. Lomawaima said archival records show that in 1926, Cora Carr, their mother, requested her sons be allowed to attend Chilocco.

In the era her father and uncle attended Chilocco, Lomawaima said children were allowed to go home to see their parents on breaks, a significant difference from earlier school policy. Despite some improvements, though, “it was a very harsh environment” built on strict military discipline and regimented schedules, she said. The school used methods like the “beltline strategy” to encourage students to regulate themselves.

“They would line the boys up in two lines, like running a gauntlet. They hit him with their belts,” Lomawaima said. “As my dad said, if some guy had it out for you, he hit you with the buckle end.”

Lomawaima said her father had fond memories of the Saturdays he spent hunting and fishing in Chilocco Creek with his boarding school gang. He also credited the school for teaching him practical trade skills that he was able to develop into his later career as a flight engineer, but he said those skills didn’t make up for destroying his family.

More significant boarding school reforms came during the Civil Rights era, though White Hawk said there were still some reports of brutal treatment. During this later period many Native American families developed school pride after multiple generations attended a specific boarding school. Many students have shared fond memories of boarding schools and express regret that so many were closed.

Patty Talahongva, a Hopi journalist for Indian Country Today who attended Phoenix Indian School in 1978-79, said, “Things changed in the boarding schools over time. What did not change was the quality of education. It was always substandard.”

Later-era students at some schools took back the experience and made it their own. Talahongva said when she was attending Phoenix Indian School, students shared their culture through tribal clubs and powwow groups. But there were still vestiges of the militarized regimen that had characterized early boarding schools.

Attendance was no longer mandated but Talahongva decided to go to Phoenix Indian School in 1978 because there wasn’t a high school on the Hopi reservation.

“The only option on the table was to go to boarding school, and is that being forced?” Talahongva said.

Experts say trauma from the boarding school era has been passed through generations of Native American families. They point to the lasting effects of historical trauma as causes of the high levels of PTSD, incarceration, violence and poverty Native American youth face today.

But White Hawk said the trauma isn’t just historical –– it’s present-day.

“I’m 66 and we still have the generation right here who are the last to have gone to those kinds of boarding schools,” White Hawk said. “It’s not in the past at all.”

But Lomawaima said that, while historical trauma is real, blaming everything on it can mask the fact that, “there’s bad stuff happening now.” It can imply that victims are permanently broken and often lets the victimizers off the hook, undermining the strength and resilience Native people have shown by surviving centuries of colonialism.

Talahongva said the boarding school system was devastating because generations of Native Americans grew up away from their families and culture. If young people returned to their tribes, she said, they didn’t know their traditions or how to be parents.

“We’re healing ourselves,” Talahongva said. “And every generation gets a little bit better.”

Experts like Lomawaima and Brenda Child, professor of American studies at the University of Minnesota, question whether too much emphasis is placed on boarding schools as the main cause of Natives Americans’ historic and current trauma, especially since students’ recollections of their boarding school experiences are so disparate.

In a chapter of a book she contributed to, Child concludes that the boarding school experience does not summarize all the bad things that have ever happened to Native Americans. Rather, it’s a metaphor useful for summing up the many federal policies that accumulated over “the allotment and assimilation era” to undermine tribal sovereignty and allow European settlers to claim tribal lands.

In some ways, Lomawaima’s father’s experience at Chilocco actually reinforced his cultural identity. Curtis Carr hadn’t been raised in a traditional Creek home; he learned about tribal culture from his gang at school and they developed their own culture of resistance that helped them be resilient in the face of abuse, Lomawaima said.

Lomawaima said her father taught her and her sister to always resist and question authority.

“That’s certainly not to say that boarding schools are blameless because they were not,” Lomawaima said. “But it also is just a reminder that they weren’t the only thing going on, not then, not now.”

Source photos courtesy of the Phoenix Indian School Visitor Center and K. Tsianina Lomawaima

Calah Schlabach is a master’s student at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. She worked as a graduate assistant for Global Sport Matters, a media platform collaboration between Cronkite and ASU’s Global Sport Institute. Before starting at Cronkite, she was a grant writer for a social services nonprofit in Columbus, Ohio. She previously spent time writing and editing in Vietnam and Haiti, and as a professional triathlete and university triathlon coach. Originally from St. Michaels, Arizona, she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English and a writing minor from Calvin University. She recently reported on U.S. involvement in Panama’s migration system and companies mining for minerals in Arizona’s Sky Islands