(Document courtesy of Judy Dutcher)

In a suburb near Austin, Texas, a popular and athletic 13-year-old girl named Kelly Brumbelow was found dead in a pile of firewood. Her 12-year-old friend and neighbor Terrence Sampson had stabbed her 97 times in the head and face.

The two, who were friends, had been shooting hoops in her driveway Dec. 2 1989 when Kelly’s mother called her to the phone. Terrence waited outside as she took the call.

But Terrence didn’t believe Kelly really had a phone call, according to Kelly’s mom and his former social worker. He thought it was just an excuse to ditch him.

Both said he came up with a plan. If he called her and got a busy signal, then it would prove she wasn’t lying and she actually had a phone call.

Kelly Brumbelow talks on the phone at her home in Round Rock, Texas, in the 1980s. Kelly’s mother, Judy Dutcher, says Kelly was at the top of her class in school before a neighbor stabbed her to death in 1989. (Photo courtesy of Judy Dutcher)

Terrence went back into his house and dialed Kelly’s number. She answered; no busy signal. But what he didn’t know was that Kelly’s 1989 phone had a call waiting, allowing her to hold one call while she answered another.

Thinking she had lied, he said on the phone he had a surprise for her and she ran to his house. And that’s where he killed her.

But after 27 years, Judy Dutcher, Kelly’s mother, chose forgiveness. And Sampson, at 41, was paroled early last year.

“I didn’t do it for him. I did it to get myself off the hook,” Dutcher said. “It’s not for that person that you maybe hold all of this animosity, for what they have done … it’s not for them.”

But this story starts two years before the murder.

Texas was beginning to implement tough-on-crime policies in the mid 1980s. Steven Halpert, the juvenile division chief for the Harris County Public Defender’s Office, in Texas, says back then, determinate sentencing was introduced as a compromise.

Instead of lowering the minimum age that a juvenile could be charged as an adult to 13, Texas became one of the first states in the country to implement determinate sentencing, known elsewhere as blended sentencing. Texas, now allowed children as young as 10 to face up to 30 years of probation or incarceration for certain crimes.

Sampson, who was 13 by then, was given the maximum sentence and incarcerated at the Giddings State School, which at the time housed kids who committed capital murder and other violent felonies.

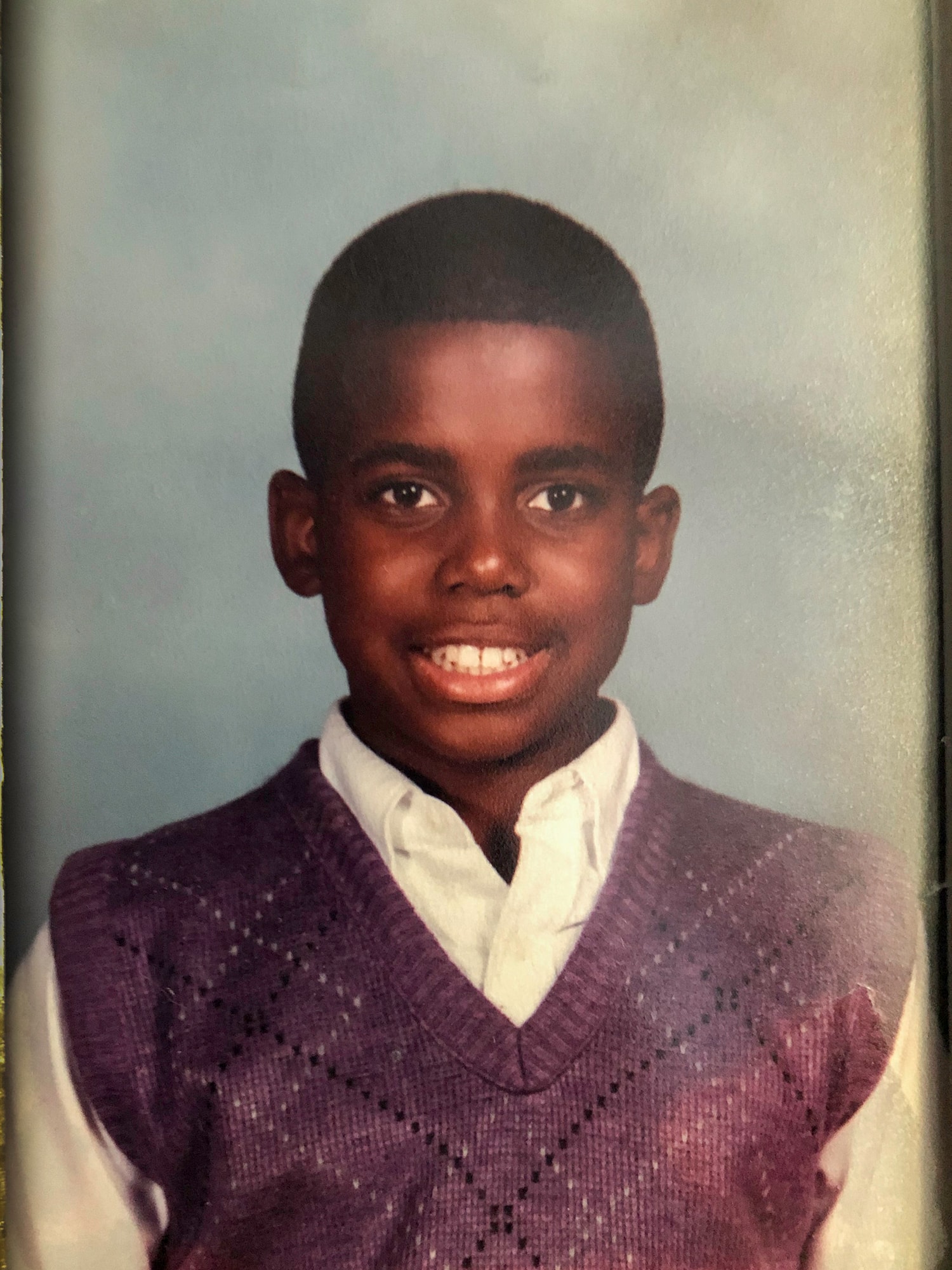

Terrence Sampson was 12 in December 1989 when he brutally murdered his 13-year-old friend and neighbor, Kelly Brumbelow, in Round Rock, Texas. (Photo courtesy of Terrence Sampson)

There, social services administrator Carolyn Esparza helped him realize and process what he had done. She remembers him telling her about that day in December 1989.

“He said, ‘And then I saw her running across the front window.’ And I said to him, ‘Terrence, she was running to your house,’” Esparza said, pointing out to Sampson, that only a friend would be excited enough to run over.

“And he broke down,” Esparza said. “He understood. She did like him. She cared about him. She was his friend … and the grief was just extraordinary.”

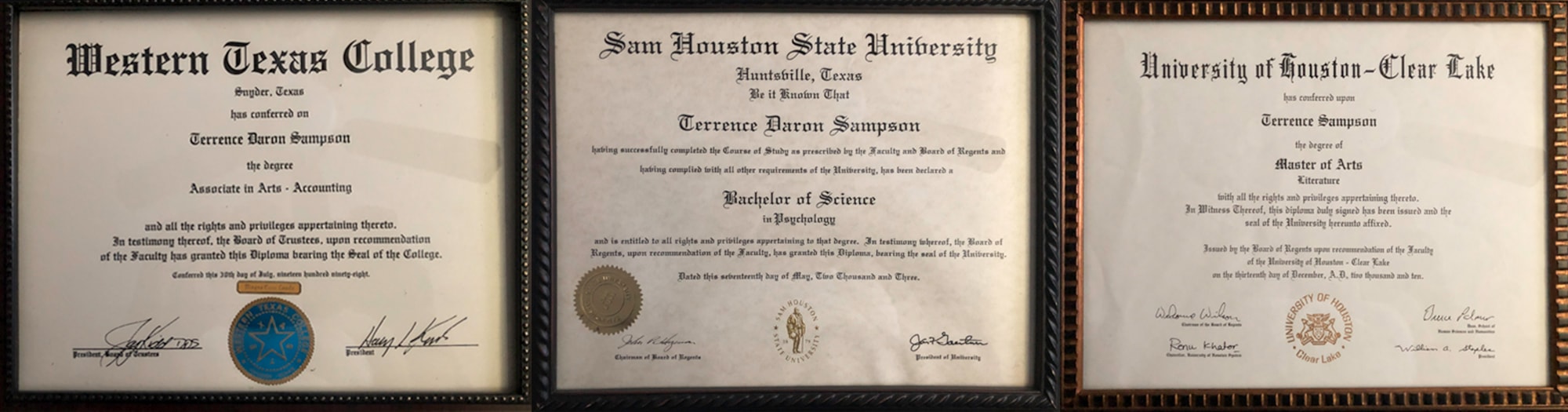

Sampson went on to get a GED certificate and a high school diploma, and during his 29 years behind bars, he earned an associate’s degree in accounting, a bachelor’s in psychology and a master’s in literature.

But that was in the future.

At Giddings, Sampson joined a capital offender program in which juveniles talk about their crimes, reenact them and then act them out again, this time from their victim’s perspective.

Dutcher, Kelly Brumbelow’s mother, says the psychologist who oversaw the program wrote in a report that Sampson “acted the part” and was just “going through the motions.”

Another problem arose five months before a judge was to decide whether he finish his term in adult prison or be paroled. Sampson would later write in his memoir, “Chasing Redemption,” that he was accused of saying that if he got out, he would go and kill Kelly’s mother and then everyone in Giddings’ administration.

“The assistant superintendent played the final trump card,” Sampson wrote in his memoir.

“He told me that if I didn’t admit to saying what I was accused of saying I would not be allowed to play in the upcoming football game on campus and I would be placed in isolation for the five month remainder of my time at Giddings. That statement shook me.”

So he admitted to it.

A month before his 18th birthday, he was called before the court once more. He had almost 25 more years to serve and was aging out of the juvenile system. The court transferred Sampson to adult prison, where he was held for the next two decades. During those years he wrote the book, “Chasing Redemption.”

“I apologized to my victim, I apologized to my victim’s mother, I apologized to my community. I thought that it was important for people to understand the man that I was in 2010 and not the child that I was in 1989,” Sampson said, adding that he will never forgive himself.

“I don’t think that I can ever catch redemption because what I had done can never be fixed,” he said.

But he did wish forgiveness from others. An excerpt from his memoir reads: “When I say I wish to receive forgiveness from those who still despise me and possibly wish me harm, it is in large part because I know the freedom and peace and great relief forgiveness brings, and I wish that for them, too.”

He again was denied parole in 2010, when he was 33.

“Ms. Esparza told me plainly at 14, 15 (years of age), ‘They’re never going to let you go,’” Sampson recalled. “My case was politicized.”

In prison, he joined another restorative justice program, Bridges to Life, a 14-week international faith-based course led by retired teacher Dolores Stoughton, one of the program’s regional coordinators.

“He was pretty transparent … and transparency is one of the things we really ask them to work toward,” Stoughton said. “I felt like he encouraged the other men when they were having difficult times.”

On Jan. 4, 2019, Sampson was paroled after 29 years. He now has a fiancé and two children, “my (6-year-old) princess,” and a 10-month-old son.

Terrence Sampson was released from prison in 2019 after serving 29 years of a 30-year sentence for the 1989 murder of teenager Kelly Brumbelow. He says he can never forgive himself for what he did. “I look at my son now and I can’t imagine something like that happening to him.” (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska / News21)

“People wanted me to name him Terrence Sampson Jr.,” Sampson said. “But I didn’t want him to grow up with the blood on his name that I have on mine.”

But referring to the murder in 1989, “I look at my son now and I can’t imagine something like that happening to him.”

Kelly was the middle of three girls. Her younger sister lived with her father in New Mexico and her older sister had already moved out. It was just Kelly and Dutcher.

“My oldest daughter does not talk about Kelly at all … she can’t. And my youngest daughter was so damaged by this that she has a world of issues and I have three young adult grandchildren that know almost nothing about their aunt,” Dutcher said.

Sampson’s father found Kelly’s body on Dec. 3, Dutcher said. He led her to the woodpile in his backyard.

“I was a blithering idiot. I was thinking as I ran up to that stack of firewood, ‘What is a mannequin doing in firewood?’” Dutcher recalled. “And when I got up close, I looked and just started screaming at the top of my lungs.”

“I turned it into my mission to keep him incarcerated (for) as many of those 30 years as I could, because in my mind, 30 years wasn’t near enough for the life that he took,” she said.

Judy Dutcher holds a portrait of her daughter, Kelly Brumbelow, in her home in Texas. “When I share my story, I’m Kelly’s mom again,” she says. (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska / News21)

Dutcher says within two weeks of Sampson’s arrival at Giddings State School, she went to the superintendent with a photo album of Kelly. She asked him to never let Sampson have a kitchen job where he could access knives.

In September 1991, she presented two bills to the Texas Legislature “and got two juvenile laws changed in that same session,” Dutcher said.

One law extended the maximum determinate sentence by 10 years. Texas children as young as 10 can be tried under determinate sentencing, for certain crimes, and face up to 40 years.

“My argument was it doesn’t matter if he was 12, 22, 42, or 82; my child is still just as dead,”

Dutcher said. “Some people think, ‘Man, 40 years for a kid, they deserve a break. Their brain isn’t fully functioning.’ I’ve heard all of this. I’ve studied all of this. But anyone that can intentionally inflict that much damage, no one will ever be able to convince me that they don’t know what they’re doing.”

She also became heavily involved in the Texas Youth Commission, now called the Texas Juvenile Justice Department. At one point she learned that Sampson was permitted to leave Giddings with his parents for the weekend if they kept within a 30-mile radius of the facility.

It’s “kind of crap that nobody else had pushed back on (this)” Dutcher said. “The only three crimes that they had at Giddings State School at this point in time were aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, rape or murder.”

She got that policy changed within the Texas Youth Commission, she said.

Dutcher protested Sampson’s first chance at parole in 1995, when he was transferred to adult prison. She continued to protest at every parole hearing until 2018.

In the late 1990s, she joined Bridges to Life. It was the same program Sampson participated in years later.

“My psychologist called me a walking time bomb,” Dutcher said.

The Bridges to Life topic in week 10 is about forgiveness, Dutcher said, and she went on for years teaching “week 10” without ever coming to terms with her own case.

Kelly Brumbelow and her mother, Judy Dutcher, in a holiday picture in 1987. Dutcher says that her work with the Bridges to Life program helped her forgive her daughter’s murderer, nearly three decades after her death.“I didn’t do it for him,” she says. “I did it to get myself off the hook.” (Photo courtesy of Judy Dutcher)

“Bridges to Life … helped me to realize that no matter what someone does, they’re still a human being, and some people, no matter how horrible what they did, they’re redeemable. (But) for many, many years, I didn’t even want to see that in him,” Dutcher said of Sampson. “And so I held onto that because I needed so badly to hold on to her.”

In 2016, she had a change of heart. One of her Bridges to Life participants asked why she had never forgiven Sampson. Later that day, a second participant asked her the same question.

“Two times in one day by people that are also struggling with the same issues. It became more than I could hold on to,” Dutcher said.

So she stood up in front of the group and apologized.

“‘I am so sorry that I have been such a hypocrite and I can’t do this on my own anymore,’” Dutcher recalled. “And in our small group, I asked God .. to just help me get over it, and to forgive me for 27 years of holding on to that when I knew better, but I was just stubborn. And I left that prison that night feeling like a 10-ton weight had been lifted off of me.”

Two years later, at Sampson’s final parole hearing, she didn’t protest.

“I finally was able to forgive him for this,” Dutcher said. “(But) I didn’t do it for him.”

Jill Ryan is an Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation fellow.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.