(Photo courtesy of Ruben Saldaña)

Tens of thousands of children, mostly teens, are prosecuted as adults every year, and some serve out their sentences in prisons where most of the inmates are adults.

Nationally, no single organization tracks the number of young people sentenced as adults because each state uses an array of their own laws and variables to decide which kids should be treated as adults.

“Geography is just one component of where they live that can dictate their life chances,” said Jennifer Peck, associate professor at the University of Central Florida.

Tristan was 16 when he left his Phoenix home for a night out with friends in October 2016. When he didn’t return, his mother, Lisa White, grew concerned.

“My heart worried because he always called me if he needed a ride, if he needed for me to come pick him up or he would always let me know, ‘I’m going to stay at my friend’s’ or ‘I’ll be back tomorrow,’” said White, who stayed up all night praying for her son’s well-being.

The next morning, White went for a hike. As she sat on a mountaintop meditating, a Phoenix police officer arrived at her home. Tristan had been arrested.

Tristan, pictured at 8, is serving a five-year sentence for armed robbery with a deadly weapon, a crime he committed in 2016 at age 16. His mother, Lisa White of Phoenix, says he’s outgoing and well-liked in his community. “I will always be there for him, even though he made the mistake here that night, being there,” she says. (Photo courtesy of Lisa White)

White said one of Tristan’s friends pulled out a gun and stole someone’s phone. Although he never held the gun, she said, he was charged with armed robbery with a deadly weapon.

Based on the seriousness of the charge, he was automatically transferred to the adult criminal system and would be tried as an adult.

“Little did I know that that was going to happen to him that night,” White said.

An estimated 76,000 young people are charged as adults each year – a decrease of 70% in the past 12 years, according to a report in May by Campaign for Youth Justice, a national organization focused on youth in the adult system. Campaign CEO Marcy Mistrett said most youth are tried as adults for nonviolent crimes, such as drug and property offenses.

“People make the assumption that these kids are the worst of the worst. If you unpack that a little, it’s quite questionable,” Mistrett said.

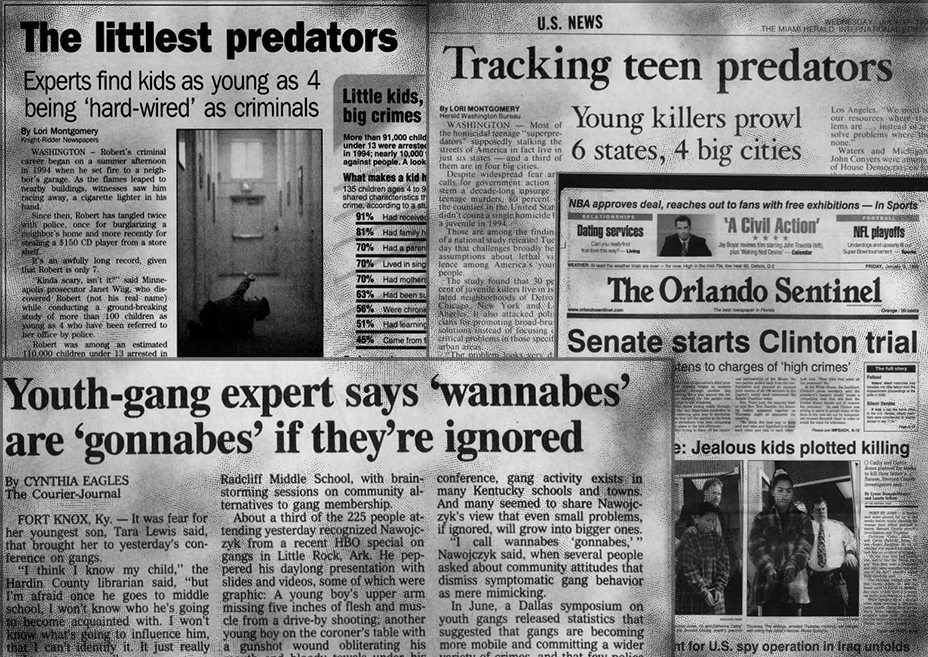

Peck said increases in juvenile crime in the 1970s and ’80s fostered a “get tough” movement that resulted in more severe punishment.

“The idea was, if we got tough on crime, then crime rates would come down,” said Preston Elrod, professor emeritus at the School of Justice Studies at Eastern Kentucky University.

By the 1990s, crime and the concept of the “super-predator” had moved to the forefront of American politics. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 – the largest U.S. crime-control bill in history – was signed by President Bill Clinton and largely written by U.S. Senator Joe Biden.

“There was a lot of descriptors that really dehumanized children,” Mistrett said. “You look at your teacher wrong, you got incarcerated. You talk back to your grandma, you got incarcerated.”

By the mid 1990s, more than a dozen states began expanding their laws to allow youth to be tried in adult court, according to statistics by the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Attorney Donna Sheen, who directs the Wyoming Children’s Law Center, said sending youth to the adult system allows for longer sentences, whereas in the juvenile system they will be released when they age out.

Scott Warner of Gillette, Wyoming, contacted Sheen to get help for his son, Dale Warner, who was 14 when he was tried as an adult after bringing two of Warner’s guns to school in 2018.

Dale – a Lakota Sioux – bounced among 20 foster families before Warner and his now ex-wife adopted him in 2015. Because of childhood neglect, Warner said, Dale suffers from fetal alcohol syndrome and reactive attachment disorder.

Dale Warner, 13, poses for his junior high football photo in Gillette, Wyoming. Dale, who had a traumatic upbringing and spent many years in the foster care system, was 14 when he brought guns to school in 2018. He’s serving a 20 year sentence for aggravated assault and possession of a deadly weapon. (Photo courtesy of Scott Warner)

Dale’s natural father had died a few days before he took the guns to school, Warner said, and the teen was struggling to accept that “he lost a portion of what he thought his family was going to be like.”

Warner said his son was going to “eat a damn bullet” in the restroom before school, but a friend came and got him, adding that his son’s poor mental state was a contributing factor.

The prosecutor sent Dale’s case to the adult system for nine charges of first degree attempted murder based on Dale’s confession.

The Warners appealed, asking a judge to reconsider Dale’s family situation, developmental and mental health issues, substance abuse problems and lack of criminal history. Their request was denied.

“It’s like dumping all your time and effort into building something and all of a sudden a hurricane comes through and just rips it right out of the ground,” Warner said.

“They took a really harsh approach in making that decision,” said Sheen.

Dale was sentenced up to 20 years in prison after pleading guilty to a pair of lesser felony charges.

The most recent statistics from Campaign for Youth Justice found that Latino, Black and Native children are significantly more likely to be tried in adult courts.

“Some people are not as good about … checking their biases at the door when they put on the black robe,” said Elrod at Eastern Kentucky.

Extreme disparities are found in Latino youth, who are 40% more likely than white youth to be admitted to an adult prison, according to a 2016 report by the Campaign for Youth Justice.

In 2017, Black youth accounted for 35% of cases in the juvenile system but represented more than half the young people who were transferred to adult court by a judge, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. And although the total number of youth transferred by a judge from 2005-17 has declined significantly, the number of youth of color has increased over time, the initiative said.

“(It’s) impossible to separate it from a racial justice issue at this point,” said Mistrett, who has led the Campaign for Youth Justice since 2014.

Nationwide, African-American children are 8.6 times as likely as white children to receive adult prison sentences, and Native youth are 1.84 times as likely as white kids, according to Campaign for Youth Justice.

Lisa White, a member of the Navajo Nation, believes the “school-to-prison pipeline” affected the legal outcome for her son, Tristan. (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska / News21)

“We were indigenous brown people,” said White, Tristan’s mother. “We were always targeted — Black and brown communities.”

She said she educated her kids about how to interact with authority after the high-profile death in 2012 of Trayvon Martin, 17, a Black teen who was shot by a neighborhood watch captain in Sanford, Florida.

The night Tristan was arrested in 2016, a police helicopter circled overhead and guns were drawn on her son, White said, adding that Tristan followed her advice and dropped to his knees as officers approached.

Young people usually enter the adult system in one of three ways — and only one of them involves a juvenile judge.

Some states have granted prosecutors, in addition to judges, the power to transfer young people to the adult system, which is what happened to Dale Warner in Wyoming. Some states also allow juveniles to be automatically tried as adults if they commit violent crimes and are of a certain age, which was the case of Tristan, who was 16.

“You can see just based on those different mechanisms, how if you have two youth who look exactly the same – in potential, their prior histories, their current offenses, race, ethnicity – how they can have very, very different outcomes simply depending on what state they live in,” Peck, of the University of Central Florida, said.

At Tristan’s first court appearance, White said, he was seated in the same row as adult suspects.

“My hands were tied. … The system is so unfair for juveniles, it’s so unfair,” White said. “Me experiencing that as a mother, from the get-go, I was so disgusted.

“I couldn’t believe how the criminal justice of the state of Arizona thought this was OK.”

Automatic transfer — known in most states as statutory exclusion — is an option in more than half the states, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. They include California, Maryland, Iowa, Georgia and Arizona.

Statutory exclusion allows children to automatically be sent to the adult system based solely on the type of crime alleged and the age of the accused. Mistrett said this means a judge has no say in the matter.

Georgia and Florida were among the first states expanding options for transferring youth to the adult system by granting prosecutors the power of direct file, which bypasses juvenile judges.

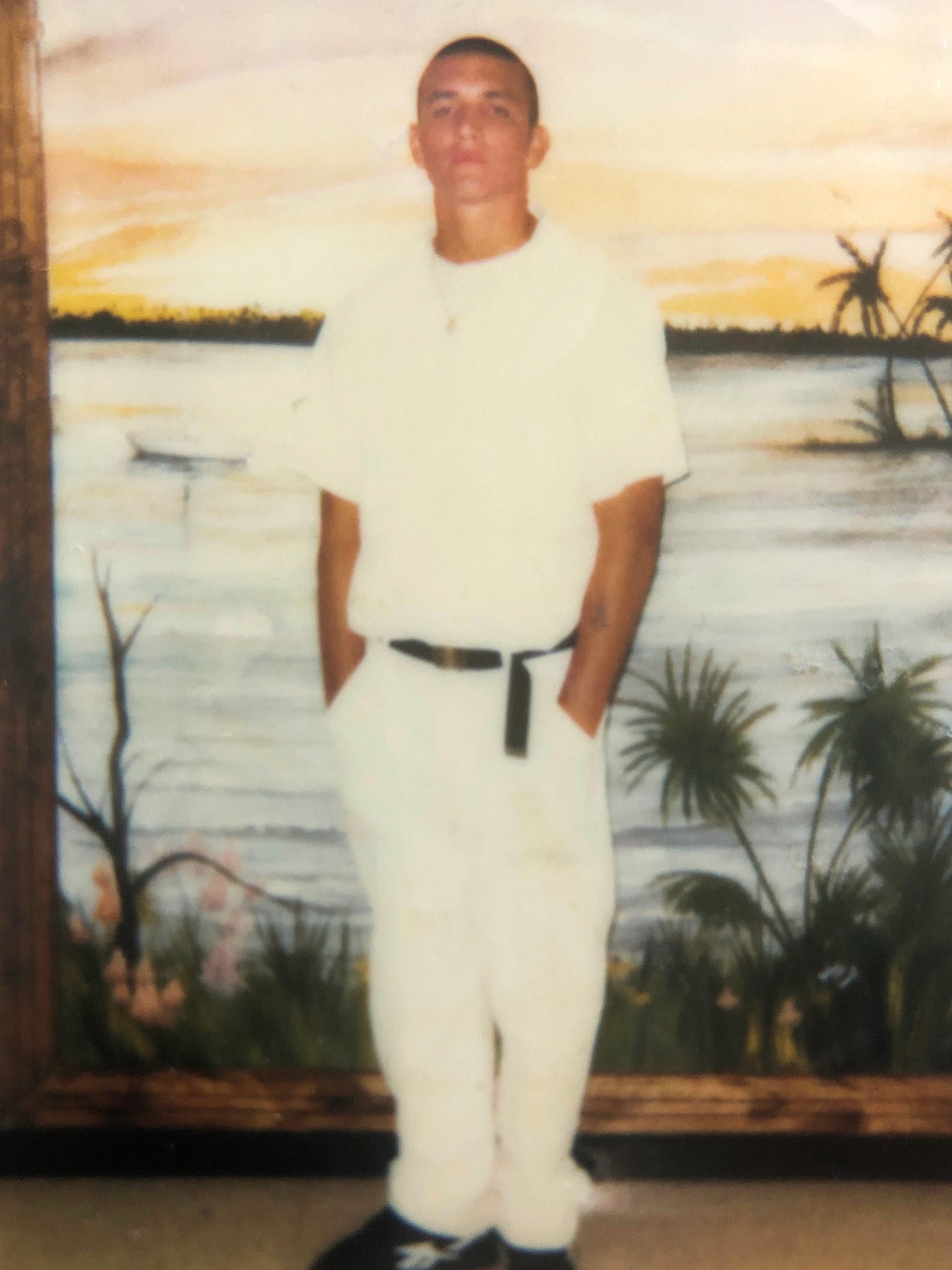

Ruben Saldaña of Miami landed in the adult system in the early 1990s because of a direct file.

An interracial Latino, Saldaña was 16 when he was charged as an adult for grand theft auto in 1992. He had been involved in gangs and already had a handful of interactions with the police.

“There’s thousands of kids that are able to go through these programs and be given a second chance before getting waved over as an adult,” said Saldaña, who now uses martial arts to deter young people from following in his footsteps. “I had never been given that second chance.”

Ruben Saldaña’s gang involvement started at 12, when gangs offered him protection from beatings in middle school in Homestead, Florida. When he was arrested for auto theft in 1992, he had his gang’s symbol shaved into his hair. He believes his gang affiliation was a big reason why he was transferred to the adult justice system. (Photos courtesy of Ruben Saldaña)

Florida stands out in its use of direct file. In fiscal 2015-16, more than 98% of juveniles sent to the adult system were at prosecutors’ discretion, according to a 2019 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

“The prosecutor had the absolute right and the judge had no say in it,” said Kelly Richards, a public defender for young people tried as adults in Escambia County, Florida, which has historically high rates of transfer. “A juvenile judge could want to keep the case in juvenile court, but the prosecutors have the power.”

Experts caution that giving prosecutors sole discretion on transfers leads to wide discrepancies across the country, and even at the county level.

“That certainly gives us pause,” Mistrett said of direct file.

In Florida, which ended automatic transfers in 2018 – those based on the type of crime and the defendant’s age – prosecutors make the decision, Mistrett said, and it “gives us an opportunity,” instead of automatically sending youth to the adult system.

Miami-Dade County has made strides to reduce the number of young people tried as adults, said Tamara Gray, assistant public defender for the county.

“We were leading the whole doggone United States,” she said, adding that Miami-Dade handles transfers now in a way “more conducive to what we now know about children” and their brain development.

In the late 1980s, a new policy came into play: blended sentencing, which could allow courts to hand out sentences that spanned both juvenile and adult systems. Texas has a blended sentencing law called determinate sentencing, which allows a child accused of a certain crime to face up to 40 years in prison or probation. If convicted, the child would be held in the juvenile system until they age out, then transferred to the adult system.

Fourteen other states have similar laws, called juvenile blended sentencing, in which children potentially face an automatic transfer to the adult system.

“The primary motive … is to give states more flexibility in how they deal with some young people who have engaged in crime,” Elrod said. “It provides the opportunity to be harsher, maybe, in some instances.”

At 16, Ruben Saldaña’s first impression of adult jail was the smell: “piss and metal.”

“The inmates were knocking out the lights to make it dark. It was definitely the Twilight Zone for me at a young age going into the county jail,” he recalled.

Children who end up in the adult system aren’t likely to have the same options for rehabilitation, Elrod and others say.

“Adult correctional facilities are not places of enlightenment. They’re not places where there is a lot of therapy and treatment and rehabilitation going on,” Elrod said.

Sheen worries that young people like Dale Warner, who have long sentences and are at a crucial age for development, won’t be well prepared to re-enter society.

“He’s going to have far more challenges than if we had treated him as the juvenile he was and provided the services and the supervision that he needed in the juvenile court system,” she said.

Although transfers were created to deter juveniles from committing crimes, the rate of reoffending for youth in the adult system is higher than youth in the juvenile system and often involve more serious crimes, according to a 2010 report from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Ruben Saldaña, far right, poses with participants in his Ru Camp mixed martial arts training program in Miami. They compete around the world, and last year traveled to Rome to the inaugural Youth MMA World Championship. He hopes his program can deter at-risk youth from following in his footsteps and avoid a life of crime and incarceration. (Photo courtesy of Ruben Saldaña)

“I was going to be a victim or a hardened criminal because (at) 16 in an adult (facility), you don’t have choices,” Saldaña said.

Being convicted as an adult only pulled him deeper into the life of crime, he said, and after his release, Saldaña returned to gang life.

“When you are living that street lifestyle, and you go to prison and you come out, your credibility just went up a whole bunch,” he said.

After his release, Saldaña was charged with manslaughter in 1999 and served 15 more years in prison. He now runs a youth mixed martial arts program out of his backyard, and his students compete all over the world.

“My heart is focused on youth crime prevention because, had I had a program or an outlet like this when I was younger, I would have avoided that prison trip, which eventually led to 19 years in prison,” he said.

Delia C. Johnson is a Donald W. Reynolds Foundation fellow, and Jill Ryan is an Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation fellow.

If you or someone you know is in need of help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or text 741-741 to connect with a trained crisis counselor right away.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.