(Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Rodriguez)

Isolation. Timeout. Lockdown. The hole.

Solitary confinement goes by many names, and it can be employed as arbitrarily as the language used to define it.

“There is no single standard for anything in the United States when it comes to crime and punishment, which is usually to everyone’s detriment,” said Ian Kysel, a visiting assistant clinical professor of law at Cornell Law School.

“In the area of conditions of confinement, that really continues to be the case. There’s really no enforceable national standards for anything in relation to minimally adequate conditions of confinement.”

Solitary confinement has its roots in the Quakers, a Protestant sect exploring more humane ways to treat criminals in the late 18th century. Quakers used isolation as a means of purification through introspective prayer — a form of penance.

The practice has since transformed and been institutionalized throughout the U.S. justice system, including in juvenile facilities as a means of discipline, protection and treatment.

Roughly 20% to 26% of youth reported being isolated during their time in juvenile detention. Of these, 87% reported they were isolated for more than two hours, while 53% said it was longer than 24 hours, according to a 2016 report by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

“Solitary confinement and other forms of isolation remain all too common in juvenile facilities,” said Karen Lindell, a senior attorney at the Juvenile Law Center. “As described in our 2017 report on the use of solitary confinement, almost half of juvenile facilities report using isolation to control behavior, and more than two-thirds of juvenile defenders we polled say they have clients who spent time in solitary.”

Rule 45.1 of the UN’s “Nelson Mandela Rules” of internationally recognized guidelines states that solitary confinement “shall be used only in exceptional cases as a last resort, for as short a time as possible.”

At the national level, a federal law in 2016 prohibited the use of solitary confinement and involuntary seclusion to punish children — but it’s only applicable to those in federal Bureau of Prison facilities. However, across the country, it’s up to state and local officials to regulate the use of solitary confinement.

Advocates, researchers, legislators and psychologists agree on the long-lasting, detrimental effects solitary confinement has on youth and adults alike. Despite overwhelming evidence and pressure from these groups, solitary confinement still is utilized in nearly every state for one reason or another. According to the National Conference of State Legislators, 16 states use it without limitations.

One of those states is Louisiana, where juvenile detention centers follow standards outlined by the state’s Department of Child and Family Services. Long-term correctional facilities follow standards outlined by the Office of Juvenile Justice.

These standards mainly address the process employees must follow after placing a youth in room confinement, room isolation, protective isolation or administrative segregation. Included are mandatory check-ins and proper documentation.

“I would say that those standards are still lacking. They still allow kids to be confined in their cells for too long,” said Rachel Gassert, policy director at the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights. “It’s certainly of no value and it’s very harmful.”

Isolation can have an almost immediate psychological impact and cause lasting trauma in adults, research has shown, but experts say its effects on young people are more detrimental because their brains still are developing.

The extensive psychological effects of solitary can include hallucinations, anxiety, rage, insomnia, self-harm and suicidal thoughts and attempts, according to a 2011 report by Human Rights Watch. Physical damage includes lack of adequate exercise, physical changes, stunted growth, inadequate nutrition, hair loss and problems menstruating.

Experts say young people placed in solitary are more at risk to develop depression, engage in acts of self harm and attempt or die by suicide. Those with a history of mental illness, trauma and abuse are even more at risk.

This was the case for Solan Peterson, 13, of Louisiana. On Feb. 1, 2019, Solan was sent to Ware Youth Center in Coushatta after setting a roll of toilet paper on fire in his middle school restroom. Four days later, he was placed in solitary confinement after taking apart a lamp and using it to break the lock on his cell door.

Solan Peterson was sent to Ware Youth Center in Coushatta, Louisiana, after he was accused of setting a roll of toilet paper on fire in his middle school in 2019. After four days in solitary confinement, the 13-year-old died by suicide. In response, his family founded Team Solan Foundation, a nonprofit that provides scholarships for youth to play hockey. (Photo courtesy of Ronnie Peterson)

On Feb. 10, Solan died by suicide in the room he was confined.

“I think it was a major contributor to his death,” said his father, Ronnie Peterson. “He was not the type that would have survived long in solitary confinement.”

Two days before Solan took his life, a 17-year-old at Ware had died by suicide while in solitary.

Solan was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and had a history of trauma from his time in the foster care system, where he went from home to home until his adoption in October 2013.

“When it’s like the situation we grew up in,” said Siarah Shalom Hall, Solan’s biological sister. “Occasionally after having been adopted it would cross my mind, ‘I wonder if my biological parents are still alive? I wonder how they’re doing or if one of them have killed themselves?’

“It never even crossed my mind that it was one of my siblings.”

Under Louisiana’s guidelines, corrections officers are supposed to check on young people held in solitary every 15 minutes.

They didn’t. About two that morning in 2019, Peterson and his wife received a phone call informing them their son had hanged himself using a bedsheet and died hours before. He had been in isolation for four days.

“He would have probably been OK in a regular cell amongst a bunch of other kids in Ware,” his father said. “It might not have been ideal, and he might have had some problems, but I don’t think we’d had the same outcome.”

Hall, Solan’s sister, said there were red flags that should’ve been considered before placing Solan in confinement, including his childhood trauma and ADHD medications.

“It just blows my mind that every single sign just slipped past everyone,” she said. “So many people played a role in this happening, and so many people were able to prevent it and just no one did.

“If there were even just a few more regulations. There were tons of things that could be put into place. But even if one of those things were there, this could have been prevented.”

After Solan’s suicide, his family became advocates against the use of solitary confinement, working with various groups and lawmakers, including the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, to push new legislation. In June 2019, Gov. John Bel Edwards signed House Bill 158, commonly known as Solan’s Law.

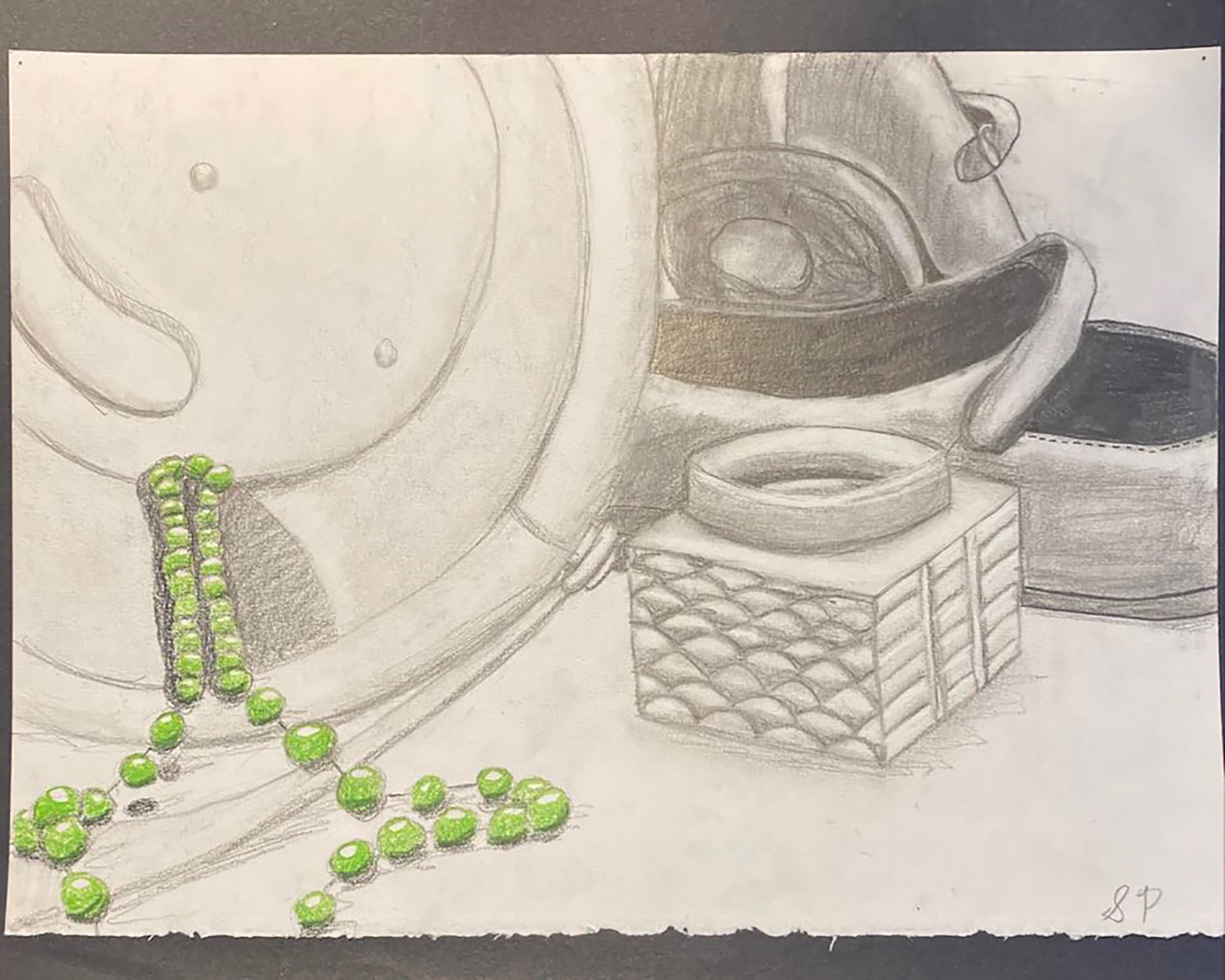

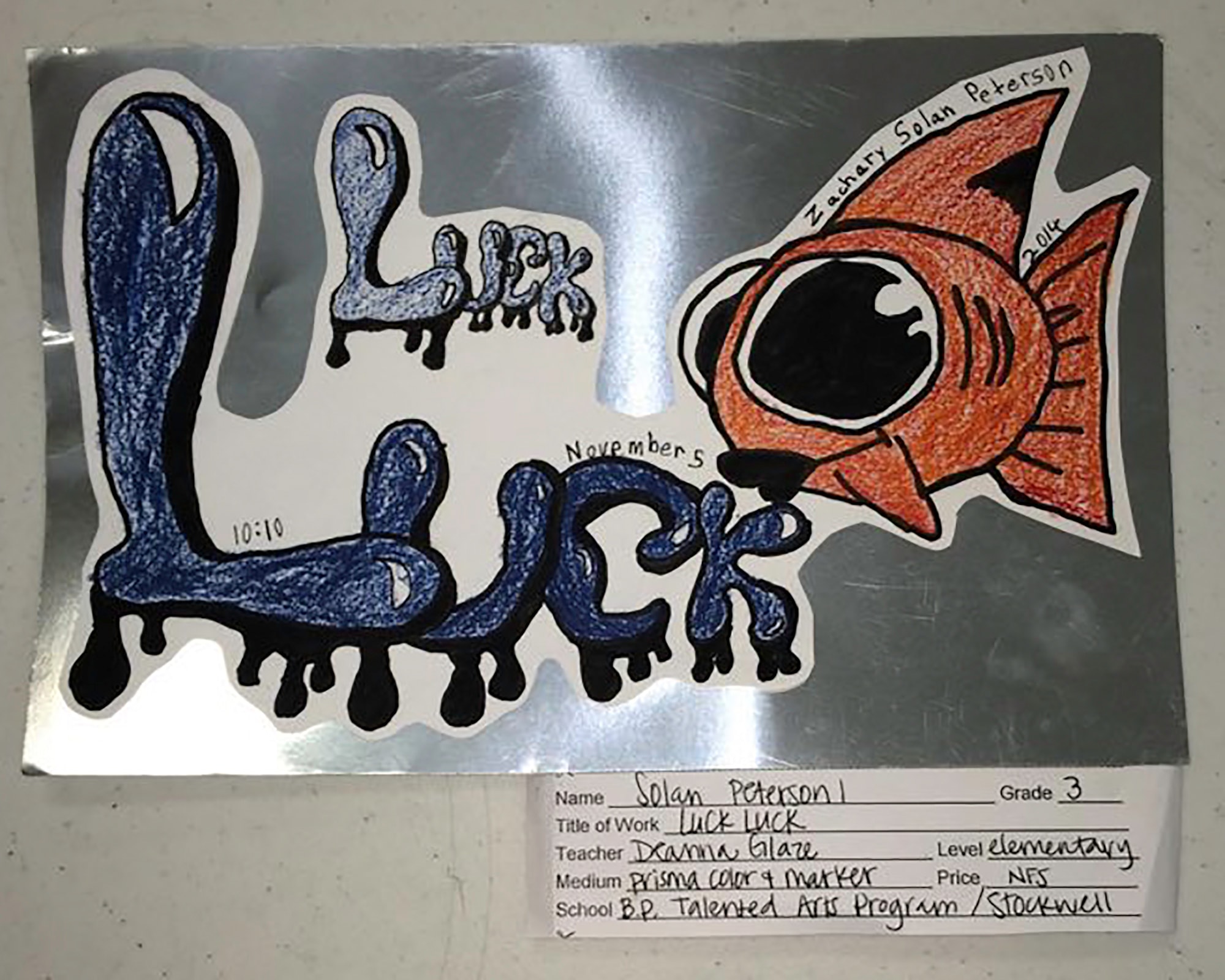

Solan Peterson’s parents say he was extremely gifted in school as well as in art. “He had a very, very creative soul. Could draw just about anything,” says his mother, Bridget Peterson. Solan had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and had a history of trauma from his time in the foster care system. (Photos courtesy of Ronnie Peterson)

Bridget and Ronnie Peterson with their daughter, Sammy, in their home in Bossier City, Louisiana. The Petersons became advocates against the use of solitary confinement for juveniles after their adopted son, Solan Peterson, 13, took his life while in solitary in 2019. (Portrait taken remotely by Layne Dowdall / News21)

The law provides alternatives to juvenile detention in Louisiana and requires screening that takes into account any factors — such as previous arrests and mental health — that would lessen or increase a sentence.

“The idea was just to establish objective criteria that was aligned with the purpose of detention,” Gassert said. “That does not mean that a child must be detained if they meet certain criteria. But just that they should not be detained if they don’t meet the criteria.”

Although Solan’s Law doesn’t specifically address solitary confinement, it’s considered a step in the right direction as an increasing number of advocates push for Louisiana to ban the practice.

“That’s by far not all that needs to be done,” Hall said. “There is so much more. Even through this, I learned a lot that’s wrong with solitary confinement.”

Isolation practices should only be used when it’s deemed absolutely necessary through set protocols, she said, such as when a child is putting others in genuine danger.

“I would like to see all solitary confinement abolished,” Peterson said, ‘but especially for youths because I find it to be a kind of torture.”

Seven states have laws that limit or prohibit the use of solitary confinement in youth detention centers, according to the National Conference of State Legislators.

In January 2018, California enacted legislation that provides specific guidelines for juvenile solitary confinement and replaced the term with “room confinement.”

The law limits room confinement to four hours, after which the minor must be released and checked by medical staff, or given a plan detailing when he or she will be released from the locked room.

“You could have a law that bans all uses of solitary confinement,” said Lindell with the Juvenile Law Center, “and yet the system might still be very often placing kids in a room by themselves for many hours at a time, or perhaps days at a time for their own safety or for something called room confinement or isolation. There’s all these kinds of different euphemisms or terms.”

Young people often are put in isolation under the guise of protection from other detainees. This is especially common for youth placed in adult facilities, and children too young to be housed with older juvenile inmates.

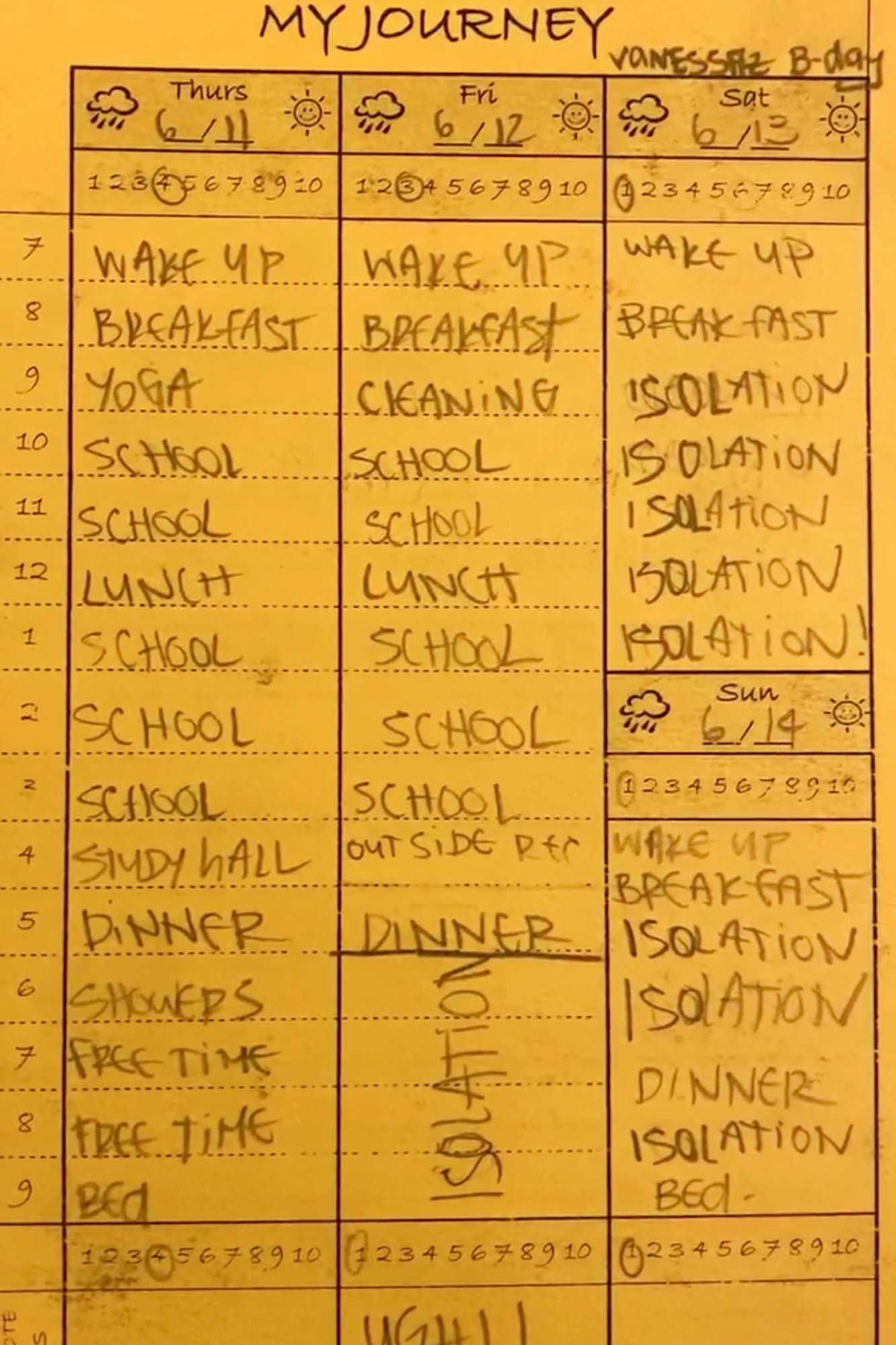

That’s why Jacqueline Rodriguez, 12, was placed in isolation at Hillcrest Juvenile Hall in San Mateo, California, in 2009. Rodriguez never had a roommate at Hillcrest because state law at the time required children to be housed with those within two years of their age.

“There was no one in there that was 12, 13, 14 — nobody,” she said.

Jacqueline Rodriguez was 12 when she was sent to a California juvenile hall, where she was isolated because she was the youngest girl there. “It was sad to me that I couldn't graduate eighth grade,” she recalls. “It was sad to me that I couldn't go to any dances. I couldn't spend time with my friends.” Now 24, Rodriquez is attending UCLA this fall. (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie / News21)

Rodriguez said her frequent drug use led to an altercation at her middle school that landed her in detention. She was originally sentenced to one month but spent roughly three years in and out of multiple detention centers after violating probation and receiving additional extensions, a process known as “bootstrapping.”

Rodriguez was sent for a 48-hour lockdown at Hillcrest Juvenile Hall on multiple occasions.

“Most of the time I would just feel … guilty,” she recalled. “I would cry a lot because I would think about my mom.”

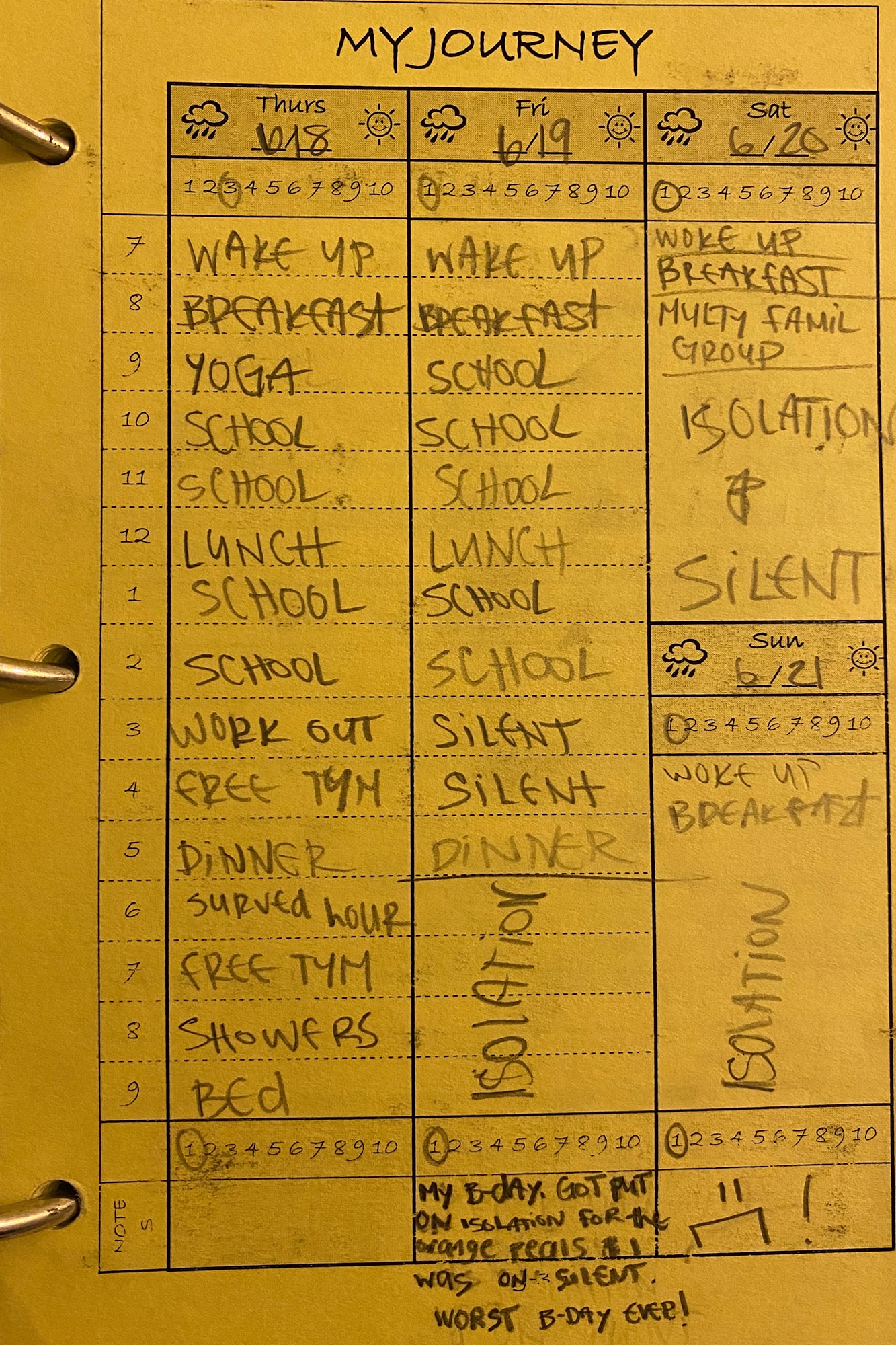

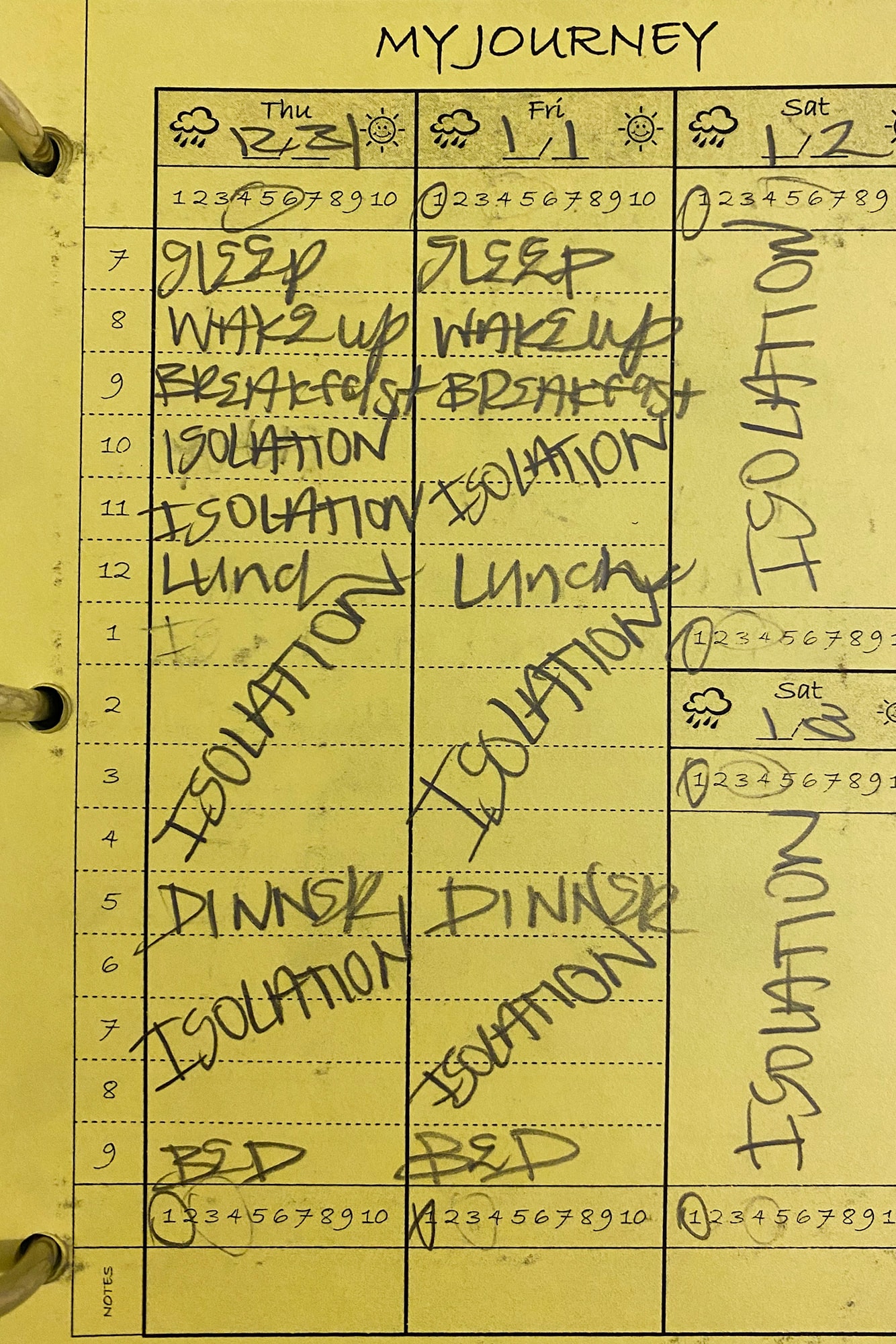

Now 24, she has kept journal entries detailing how she felt in solitary.

“All you think about is the (things) you’re going to do when you get out,” she said.

Jacqueline Rodriguez, then 12, spent the 2009 Christmas holidays at the Hillcrest Juvenile Hall in San Mateo, California. She was held in isolation because state law required roommates to be no more than two years apart in age and there were no other detainees 14 or younger. (Photos courtesy of Jacqueline Rodriguez)

Experts and advocates say isolation is a last-resort method of de-escalation that should only be used to allow a child time to calm down. If it doesn’t work, Lindell said, employees must try something else.

“You don’t need to just continue to put that person in the room for longer,” she said. “You need to get another mental health professional involved. You need to try something different. There’s a whole host of different tools, potentially, but what we don’t need is to be next to extend that period.”

Lindell said “necessary” use of solitary confinement should be for a matter of hours, never for punishment and always as a time to calm down.

Kysel, the Cornell law professor, called the continued use of solitary confinement in the U.S. despite widespread condemnation “a kind of comprehensive institutional failure.”

“You’re not going to reform the use of solitary confinement without reforming the way that we treat young people in conflict with the law,” he said.

Jos Fox is a Myrta J. Pulliam fellow.

If you or someone you know is in need of help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or text 741-741 to connect with a trained crisis counselor right away.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.