(Photo courtesy of Trevor Walraven)

Edwin Debrow, now 41, was 12 when he was convicted of murder and locked up. In August 2019, he was released from a Texas state prison after almost 28 years behind bars.

He spent nearly 70% of his life behind bars for a crime he committed while in middle school, but today he’s living free.

“I had issues with understanding how a credit card worked,” Debrow recalled. “I didn’t like the wait times at restaurants. I had issues driving … I couldn’t stay in my lane when I first got out.”

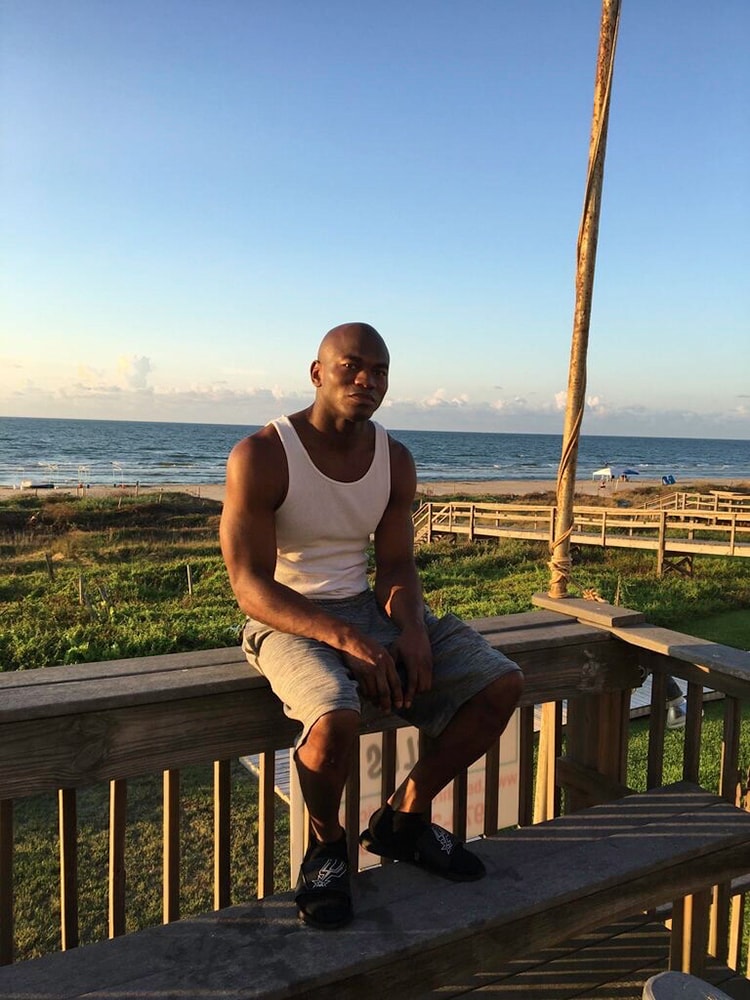

Edwin Debrow was released in August 2019 after spending 28 years behind bars for a murder he committed at age 12. He’s one of the more than 600,000 people who are released from juvenile detention centers and prisons every year. (Portrait taken remotely by James Wooldridge / News21)

More than 600,000 people are released from juvenile detention centers and prisons every year and attempt to make the difficult transition back into society, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Once offenders leave the justice system they entered as juveniles, they confront a new life fraught with unemployment, mental health difficulties and the real possibility of returning to prison.

On the morning of Debrow’s release, prison officials gave him a $50 check, a copy of his Social Security card and his birth certificate.

Instead of the uniform he had worn every day for nearly three decades, he put on a pair of white socks, blue jeans, Nike Air Max 270s, and a T-shirt reading “Edwin Debrow – Free to Be Me,” then walked out of the Carol S. Vance Unit, a prison near Houston.

“Once I walked out of that gate, it hit me,” Debrow said. “It’s happening. This is the day I waited for, for so long.”

Dozens of family members and supporters greeted him in the parking lot.

Edwin Debrow poses with his family on the day in August 2019 when he was released from a Texas prison after serving almost 28 years for murder. He now works from home for a national pizza chain. Debrow says prison life gave him mental strength that helped him after his release. (Photo courtesy of Edwin Debrow)

For young people behind bars, whether for weeks or decades, the adolescent experience is forever changed, said Linda Teplin, a professor at Northwestern University who leads the Northwestern Juvenile Project, a two-decade study tracking more than 1,800 incarcerated juveniles after their release.

“If a kid ends up arrested and misses school and then maybe doesn’t get their high school degree, their life is over,” Teplin said. “What are they qualified to do? It’s a lifelong trajectory. They might not even know how to write.”

The Northwestern Juvenile Project found many of its participants face similar obstacles to success after incarceration.

Although crimes and time served can vary greatly, juvenile offenders share a common experience upon release: The odds are stacked against them.

Many former offenders attempt to find a job or return to school, or both. But having a criminal record causes unavoidable complications.

The unemployment rate for the formerly incarcerated is about five times that of the general population, according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics. In the Northwestern Juvenile Project, only 1 in 5 males and 1 in 3 females either were working full time or in school 12 years after release.

A lack of resources, paired with little public understanding about the plight that the formerly incarcerated face, can be large obstacles for former offenders, according to Don Sawyer, associate professor of sociology at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut.

Sawyer’s research on Black and Latino men reentering society found they face a new type of discrimination after release.

“They’ve served their time, but technically people can still treat them poorly because of that mark of a criminal record,” Sawyer said.

Debrow has a murder conviction, a felony charge that’s on his record permanently.

“People have to work, especially when they are released from prison,” Debrow said. “Otherwise, they go back to doing the same stuff that got them in prison in the first place. So someone has to step up and give someone a chance.”

During his job search, Debrow applied to several companies that market themselves as “second chance” employers for former prisoners – including Goodwill and Amazon – but wasn’t hired, he said.

Debrow said people who get out of prison are “driven and they want to do the right thing.”

About two months after Debrow’s release, he got a job as a line cook at a Mod Pizza restaurant in Pearland, Texas, where he lives with his girlfriend.

Trevor Walraven, of Eugene, Oregon, spent almost 18 years locked up in nine juvenile detention facilities and adult prisons across the state. In 1998, at age 14, he was convicted of aggravated murder after shooting a lodge owner in southern Oregon and stealing his car.

Trevor Walraven, pictured in his office in Eugene, Oregon, manages case files for criminal defense teams, including some attorneys who represented him during his 18 years behind bars. "Being able to come back and contribute is really meaningful," he says. (Portrait taken remotely by James Wooldridge / News21)

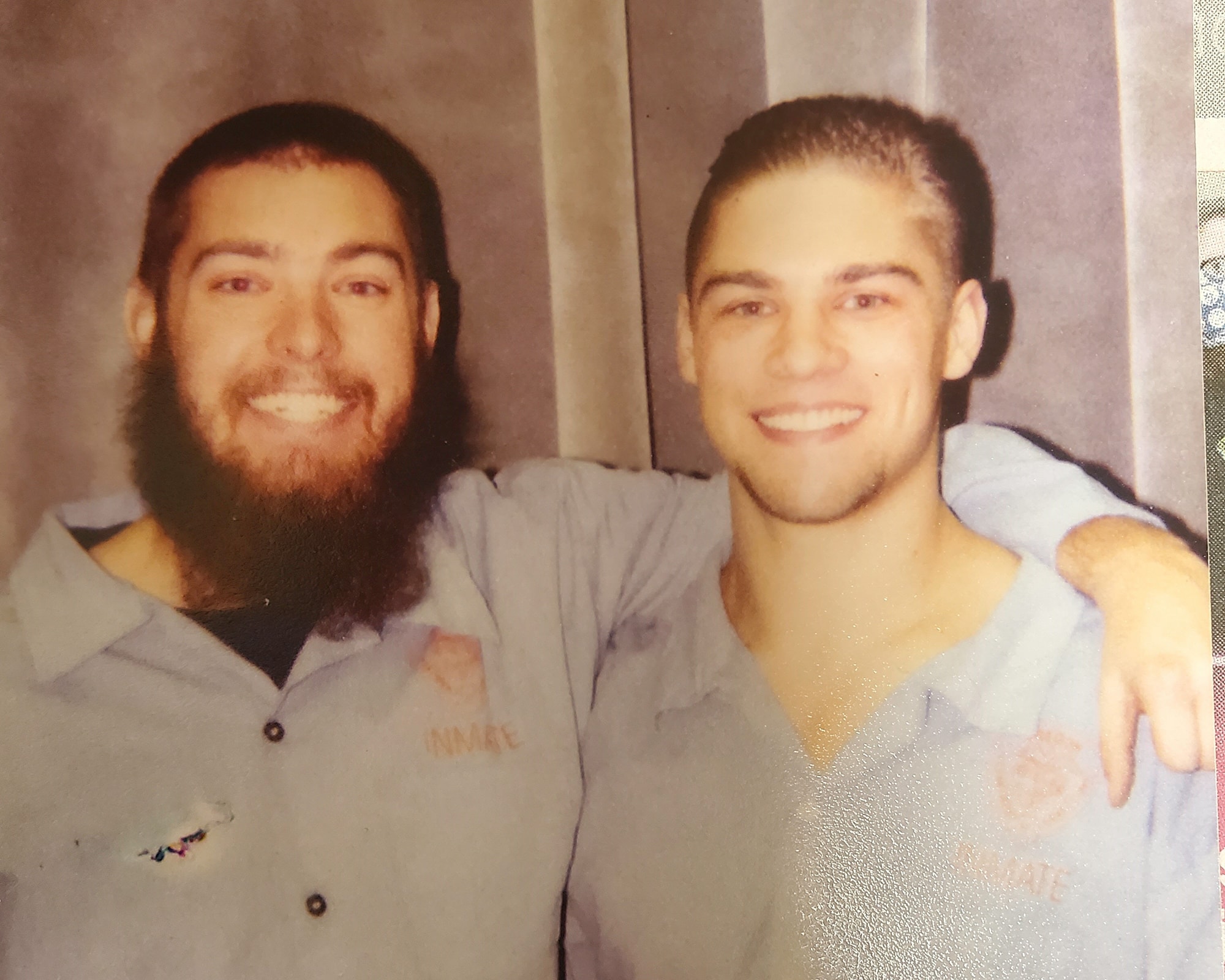

Left: Trevor Walraven, left, 8, and his brother Josh Cain, 12, in Grants Pass, Oregon, in 1992. Walraven was convicted of aggravated murder in 1998 after shooting a lodge owner at age 14. Cain was convicted of felony murder for helping his brother cover up the killing. Right: Trevor Walraven, left, and his older brother, Josh Cain, pictured in Oregon State Penitentiary, where they served about 12 years together. Walraven was released from prison in 2017 after serving 18 years. Cain was released this summer. (Photos courtesy of Trevor Walraven)

Walraven’s older half-brother, Josh Cain, was arrested at 18 for aiding and abetting the crime that his brother committed. Cain, now 40, was released in June after serving 22 years in prison. Both of them were tried as adults.

In 2000, Walraven was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole, but he was granted a “second look” hearing in 2014 and was resentenced.

After prison, Walraven worked at a staffing agency placing people – many of whom have criminal records themselves – in jobs. He now works in data management at Criminal Defense Support Services, a second chance employer, where he processes evidence and documentation for criminal cases.

“Being able to come back and contribute is really meaningful,” Walraven said of his work with criminal defense attorneys.

Sawyer said public perception also plays a role in the experience of reentry.

“If the general public doesn’t understand the fight of people reentering, then the laws will never change because there is no pressure on legislators to make any changes in the laws that address that reality,” he said.

Nearly 90% of juvenile offenders say they want to return to school after release, but only one-third do, the U.S. Department of Education reports. Several factors contribute to the gap, such as the inability to transfer academic credits from detention to a school, little or no guidance, and the poor quality of education inside a facility, experts say.

Starting when he was 10, Blake Casper spent 18 months removed from his home, jumping between foster care, group homes and eventually detention centers in Nebraska.

After he was released from his last placement at the Youth Rehabilitation & Treatment Center in Kearney, he returned to his middle school in Lexington, Nebraska in January 2011.

Blake Casper, number 74, shown on his eighth grade football team in Lexington, Nebraska, spent more than half a year at Nebraska's Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center before returning to middle school. He says he was treated differently because of his time in custody, but football was a release. (Photo courtesy of Blake Casper)

“Everyone knew the story of where I’d been,” Casper said of his return to his small town.

Casper said he felt he was treated differently by his peers and teachers. He recounted being more strictly disciplined than his classmates after getting in fights – which happened several times during middle school. Eventually, he was expelled.

“The big message I learned from it was that moving forward, my actions were going to be judged 10 times harder than everybody else’s,” said Casper, 23. “It was more of a growing moment for me.”

Most detention centers require juveniles to attend school during their sentence, which Casper did, but the program was so lackluster that he was behind in academics when he returned to school.

A 2016 survey from Council of State Governments Justice Center showed that more than half of incarcerated kids have reading and math skills significantly below their grade levels.

Courts can require inmates to see a psychologist after release because incarceration can lead to anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and substance abuse, among others, experts say.

“There’s no way that I was fully rehabilitated, or even back to normal,” Casper said. “I still had a lot of issues to work out.”

As part of the Northwestern Juvenile Project, 92% of participants reported having experienced one or more traumatic events while in detention. The most common were witnessing violence, being threatened with a weapon and being in a situation where they thought they or someone close to them would get hurt or die.

But Casper also cites family issues that preceded his removal from home at age 10. His parents’ separation was followed by his father’s suicide in 2008, and his two older brothers left home shortly after their father’s death, leaving him alone with his mother who, Casper said, was suffering from depression.

“I just sort of got left hanging in the middle of it all and grew up very quickly,” Casper said.

Blake Casper poses for a portrait in his bedroom in Omaha, Nebraska. Casper was locked in Nebraska's Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center in Kearney, a state facility for boys, when he was 13. Although returning to school after his release was hard, he earned a civil engineering degree from the University of Nebraska this year. (Portrait taken remotely by James Wooldridge / News21)

Walraven, out of prison for three years, still has difficulty managing his time to complete daily tasks. He said he has had a hard time keeping a routine for things like commuting to work or buying groceries.

He attributes this to his time in prison, where every aspect of his day – eating, showering, working and attending classes – was highly structured.

Trevor Walraven, left, stands with his brother, Josh Cain, right, and their grandparents, Paul Genthner and Doris Mercier, in July 2020. After his release from prison on June 24, Cain surprised his grandparents by showing up to celebrate his grandmother’s birthday. (Photo courtesy of Trevor Walraven)

“Everything was new to me because I hadn’t been an adult out in the free world,” Walraven said. “Being able to make choices around what I eat and how I spend my time and, you know, how I conduct myself were all, for me, really rewarding. But that doesn’t mean that they weren’t challenging.”

Debrow, in contrast, said the structure of prison solidified his self-discipline.

“When I get up in the morning, I’m one thing to the next,” Debrow said. “I don’t procrastinate.”

Debrow said he doesn’t struggle with any diagnosed mental health issues, but he processes his prison experience – which included abuse from guards and violent interactions with other prisoners – by trying to look forward.

“I really don’t even think about it much today,” Debrow said of his time in lockdown. “It’s like I had the mental capacity to accept it because I didn’t have a choice.”

Casper started seeing a counselor for a few years after his release, but the counselor deemed his visits unnecessary by the time he reached high school, he said.

About 15% of those who participated in the Northwestern Juvenile Project with “major” mental health disorders received treatment after they were released. The study found that most reported at least one barrier to receiving help, and the majority believed the problem would go away on its own.

Some, but not all, leave prison with access to supportive networks and role models. Without that support, Sawyer said, something as basic as finding a place to live can be difficult.

“When someone is released and looking for a place to stay, usually they are asked for the first month and next month’s rent, plus a security deposit,” he said. “How do you pay that when you’re coming out of prison and didn’t have an income?”

Debrow wanted a clean slate after prison, so he moved to Pearland, Texas, three hours from his hometown of San Antonio. But he still can’t sign the lease for the house where he lives with his girlfriend and her kids.

“If you have any person who wants to pay rent on a house, why should his felony background have anything to do with it as long as he makes his payments?” Debrow asked.

He considers his move to Pearland the best decision he could’ve made. But separating himself from the environment in which he grew up – a neighborhood plagued by gang violence and drugs – meant leaving his large family, with whom he remains close.

“You have to decide what’s best for you,” Debrow said. “I don’t believe any other person, regardless of who they are, family, friends, can influence a decision that you know is in your best interest.”

When Casper was considering colleges, his brother encouraged him to leave Lexington and start over. Casper attended University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s campus in Omaha, three hours away, and graduated with a degree in civil engineering in 2020.

“He was like, ‘You need to create separation from your family … and you need to sort of go live your life as you,’” Casper said of his brother. “Those words are what pushed me to go to Omaha.”

While Debrow was in prison, his elementary school teacher, Sheila Bryan, kept in touch with him, bought Debrow his first computer after his release, and they remain friends today. Megan Risdon, Debrow’s girlfriend, gave him a place to live after his release and a reason to leave San Antonio. Before he had access to transportation, co-workers gave him rides to or from work.

Edwin Debrow poses at Surfside Beach in Freeport, Texas. After serving 28 years for a murder he committed at age 12, the adjustment to outside life was challenging. (Photo courtesy of Edwin Debrow)

“I have people who were instrumental in my reentry,” Debrow said. “Regular people, not people who it was their job to do this, but people who just cared.”

One in six participants of the Northwestern Juvenile Project said they had no one on whom they could rely. The average “network size” among participants who did have a support system was 1.8 people, and those networks were overwhelmingly female.

When Casper got in fights in middle school, he felt school officials punished him differently because of his background. He said some teachers were supportive and encouraged him to get more involved at school and apply to colleges, while others treated him like he wasn’t worth their time.

“I think it goes back to those teachers in middle school that told me I wasn’t going to be anything,” Casper said of his motivation. “It was sort of my way of proving them wrong.”

Fifty-five percent of youth released from prisons or detention centers are arrested again within one year, and about a quarter of them return, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Reoffending is just one way people are sent back into the corrections system, Sawyer said. If a former prisoner fails to meet any of the terms of parole, he or she could be reincarcerated.

Debrow must remain in contact with the justice system while he finishes his sentence on parole. This includes meetings every three months with a parole officer, drug tests, a curfew and an $18 monthly parole fee until his sentence is completed in 2031.

Walraven had daily contact with law enforcement for the first few months after his release, he said. He also had to wear a GPS ankle monitor and wasn’t allowed to leave the county.

“There were a lot of layers that I certainly had not anticipated,” he said.

Casper’s record was expunged, and it never has hampered his ability to get into college or get a job, he said.

After his release and return to middle school, he feared he might get arrested again. But in high school, Casper joined the football and speech teams, which he credits for adding stability and purpose to his life.

“Once I started really seeing the success I was having in school, being involved in things, I think that (fear) sort of went away because … I’d found a home,” Casper said. “I wasn’t by myself anymore.”

Today, nearly 10 years after his release, Casper is an assistant engineer in Omaha, has a core group of friends and maintains a close relationship with his mother.

“I wouldn’t say I’ve entirely moved on,” he said, referring to his time in detention. “I guess the further I get away from it, the less effect it has.”

For those who grew up in prison, like Debrow and Walraven, it isn’t always easy to shake off the past. Both men work frequently with juvenile justice advocacy groups in their communities.

“You have to be solid on your own two feet before you can start helping others,” Walraven said.

Debrow said the only thing he misses about prison are the friends he made.

“I’m kind of drawn to prison,” Debrow said. “Something pulls me there, I have this yearning to go back and speak to guys … tell them my story and give them of some type of hope.”

Over the next few years, Debrow wants to grow his family, become a homeowner and work full-time at a criminal justice nonprofit so others don’t have to experience what he did for 28 years, he said.

“I can’t erase the effect of my criminal conviction,” he said. “But this is what I’ve been doing now, this is what I continue to do – going forward every day.”

James Wooldridge is a Buffett Foundation fellow.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.