(Portrait taken remotely by Calah Schlabach and Chloe Jones / News21)

The child welfare and juvenile justice systems are meant to help the nation’s most vulnerable children, but the two are rarely in sync, and young people who have been part of both systems make up more than half of those who get in trouble with the law.

“Once a child enters the child welfare system, the decisions made for that child by the child welfare system may, in fact, be pushing the kid towards juvenile justice,” said Denise Herz, a criminal justice professor at California State University, Los Angeles and one of the few researchers who has been studying so-called crossover kids, or dual-status youth, for years.

About 60% of children in the juvenile justice system have a history in the child welfare system, Herz said, based on her past decade of research, which she summarized in a 2019 report to the U.S. Department of Justice.

“You were either a victim and you needed help or you were an offender and you needed rehabilitation and punishment,” Herz said of the two juvenile systems, adding that the situation persists today.

The traumatic histories of foster kids often are used against them once they interact with the justice system, Herz said. Already under more surveillance, foster kids receive harsher punishments for crimes that might not even be reported if they lived with a biological parent.

“A lot of those kids, when they got arrested, were living in group homes,” she said. “So there isn’t a home, quote unquote, to go home to.”

Without a home to return to, a more restrictive environment often is a child’s only option, which can make a child seem more high-risk on paper, Herz said.

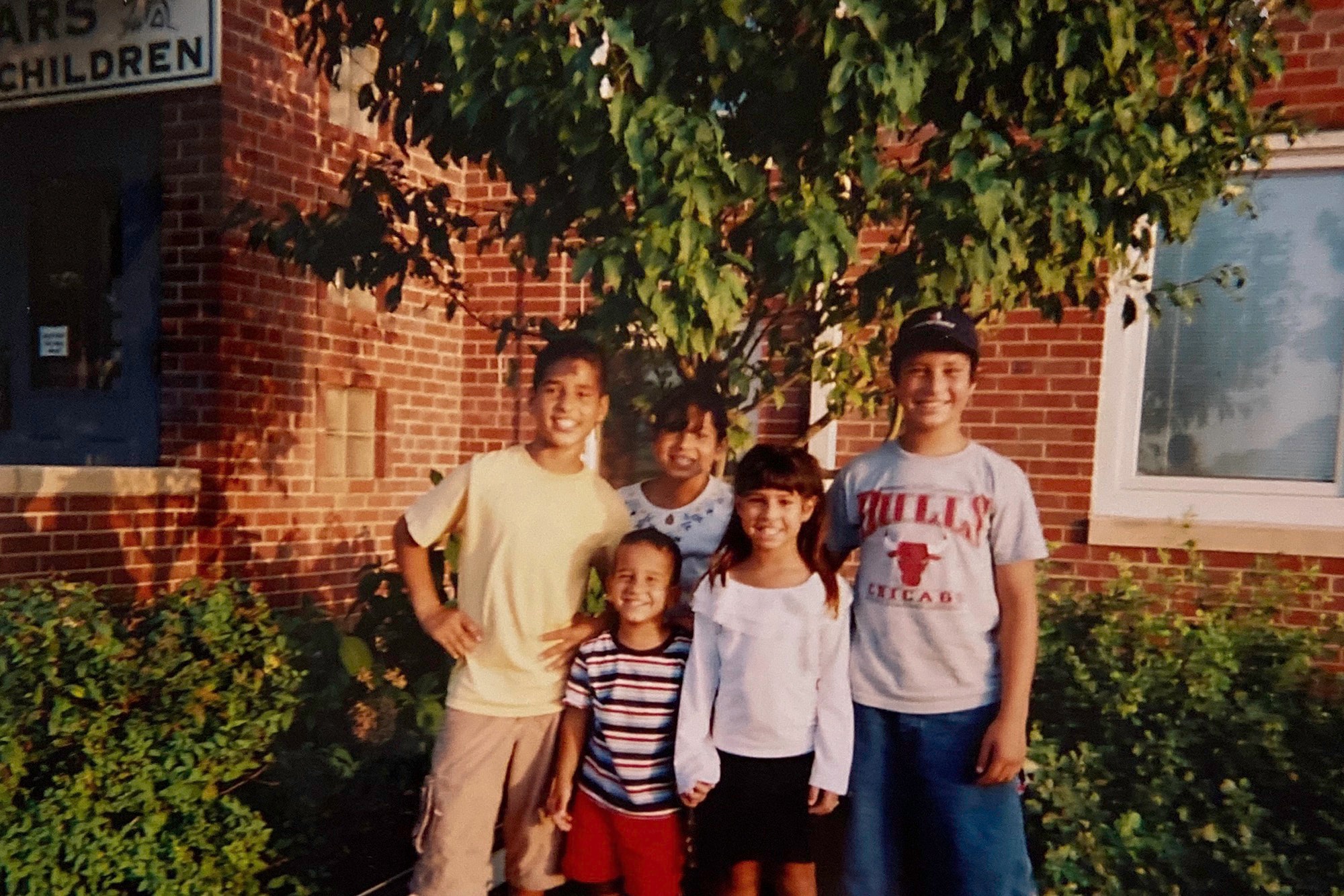

Nedhal Al-Kazahy, second from right, and her siblings lived at CEDARS Home for Children in Lincoln, Nebraska, after they were removed from their parents’ home when she was 5. Al-Kazahy, the daughter of refugees from Iraq, spent the next 16 years in and out of the foster care and juvenile justice systems. (Photo courtesy of Nedhal Al-Kazahy)

It happened to Nedhal Al-Kazahy, who was 5 when she and her five siblings were taken into child welfare custody in Nebraska. By the time she was a teenager, she had lived in more than 20 foster homes and group homes, which are more restrictive. She was 14 when her brother was murdered. She was 15 when she was raped.

“Nobody just sat down and asked me, ‘How are you?’” recalled Al-Kazahy, who’s now 22.

Unable to cope, the 15-year-old ran away from her group home. She returned two weeks later, expecting to shower and eat a home-cooked meal, but was greeted with handcuffs and a warrant. Her state caseworker recommended Al-Kazahy be placed in a detention facility for high-risk youth, despite her acceptance into a therapeutic group home, which offered mental health and behavioral support.

Al-Kazahy’s trauma was considered a risk.

Nedhal Al-Kazahy shows a tattoo of her father’s initials on her neck. Al-Kazahy was removed from her parents’ home when she was 5 years old, and says being taken from her father’s arms is the first trauma she remembers. She remained close to her dad throughout her turbulent childhood, which included over 20 foster placements and eight months in juvenile detention. She hoped to move back in with her dad when she turned 18, but he died just before she left her last foster home. (Portrait taken remotely by Calah Schlabach and Chloe Jones / News21)

“The natural trauma reaction is to flee,” said Tim Curry, special counsel for the National Juvenile Defender Center in Washington, D.C., who has worked with crossover kids for 13 years. He said criminalizing that normal response “is horrific public policy,” but it happens all the time.

Many foster kids are victims of abuse and neglect, and experts say all children in the foster care system have experienced some level of trauma. Even if the situations they were taken from weren’t violent or abusive, the act of being removed is itself traumatic.

In cases where the child has no history in the welfare system, trauma usually would be considered a factor that could lighten a child’s sentence, Curry said, but for crossover kids, “Simply being in the other system is a knock against a child.”

The justice system treats young people with child welfare backgrounds differently, according to a 2019 report in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence. This manifests in a greater chance of arrest, harsher and longer sentences for lesser offenses, and fewer chances for diversion.

“In theory, the reason why you would get harsher penalties, longer penalties is because you’re more at risk for future harms to the community,” said Herz, who was the lead author of the report. “But overall, the literature kind of questions whether dual-system youth are, in fact, higher risk.”

Experts say crossover kids like Al-Kazahy are stigmatized at every stage in the justice system, and the stigma cuts both ways: Those in the child welfare system are more likely to be detained, and for longer. And when criminal involvement pushes kids into child welfare, they are harder to place.

The racial bias that affects children of color in the juvenile justice and the child welfare systems is compounded for crossover kids. Herz’s study of three nationally representative counties found more than 70% of crossover kids are Black.

Tristan Slough of Chattanooga, Tennessee, was 14 when he was arrested for fighting. It wasn’t his first time in detention, but it was the longest. He was detained for a few weeks, then finished his sentence with a treatment program at a group home to address his mental health and behavioral needs. After serving his time, Slough was ready to reunite with his mother.

“I thought I was going home,” he recalled, “until I got put in handcuffs.”

Tristan Slough, 20, who grew up in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, is pursuing degrees in psychology and social work at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and hopes to make a difference for “crossover” kids like himself. (Portrait taken remotely by Calah Schlabach and Chloe Jones / News21)

No one told Slough why he wasn’t going home. He was driven almost three hours to a juvenile detention center in Knoxville, Tennessee, because no foster home was available yet, he said.

What he thought would be the end of prison was a continued sentence of uncertainty, growing up in state detention facilities and group homes. Eventually, he was transferred to the child welfare system.

Curry said it’s a common practice for crossover kids to be held after they’ve served their sentences because the state has nowhere else for them to go — or it hasn’t done the work to place them.

“It is fundamentally unfair,” he said. “It’s a violation of due process. It is illegal to be holding kids when there is no authority to hold them.”

Young people in the child welfare system are more likely to be criminalized for normal teenage behavior, in part because they are being watched more closely, experts and advocates say. Kids in group homes are more likely to be caught doing something wrong and reported for it.

“There is a link between behavior that would never otherwise be criminalized and behavior that is criminalized because you’re in the foster care system,” said Wende Julien, chief executive officer of CASA of Los Angeles, which advocates for thousands of children in the child welfare system each year.

When Slough was living in a group home in rural eastern Tennessee, he said, he wasn’t allowed to behave like teens who lived with their biological parents. He recalled a high school classmate who walked out of school because he was upset with a teacher.

Tristan Slough was selected for a nine-day educational trip to Australia in 2019 because of strong academic achievement at Nashville State Community College. His caseworker raised the funds for Slough to make the trip. (Photo courtesy of Tristan Slough)

“If I tried that, I would be arrested,” said Slough, who’s now 20 and in college.

The child welfare system puts children through more trauma than an average kid, he added, but “you’re not allowed to act on it, because, if you do, the consequences are way higher.”

This is especially true for foster kids who are placed in group homes or have many placements. A 2008 study that Herz co-authored found that children in group homes are 2 1/2 times more likely to enter the juvenile justice system.

Macon Stewart, a deputy director at the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform at Georgetown University, said workers at therapeutic group homes sometimes call the police to deal with behaviors they – not law enforcement – should treat.

Staff members should be able to de-escalate or use calming techniques they’ve worked on with that young person, Stewart said, adding, “They’re there for treatment.”

Although group homes often are blamed for foster kids crossing into the justice system, Herz said moving kids between foster homes multiple times is a bigger factor. A 2010 study found that 90% of kids with five or more placements eventually become involved with the juvenile justice system.

Stewart helped write Georgetown University’s Crossover Youth Practice Model, which focuses on identifying crossover kids as soon as possible, to support them and their families.

Since Georgetown started this model in 2010, 119 counties in 23 states have implemented it with promising results, including decreased recidivism rates.

In most states, when someone younger than 18 is arrested, law enforcement calls the child’s parent or guardian, who can advocate for their child, hire an attorney and give authorities some assurance their child will be held accountable. In many cases, the child then goes home with their parents.

Julien said foster children are more likely to spend the night in jail, be charged, serve time – often on longer sentences – and ultimately lose opportunities for placement in a family home.

Many diversion programs, which offer alternatives to incarceration, require someone who’s invested in the child and able to make sure the child gets to and from appearances, complete community service requirements and, in some cases, pay for the program.

If a child doesn’t have a stable family, Julien said, diversion often isn’t available so kids end up being detained longer than they otherwise would be. This was the crux of the issue for both Slough and Al-Kazahy.

Al-Kazahy said she could have benefited from an advocate before she spent eight months imprisoned in Nebraska for running away from her group home.

She entered the child welfare system at age 5 and stayed until the cutoff age of 21.

She and her five siblings were separated.

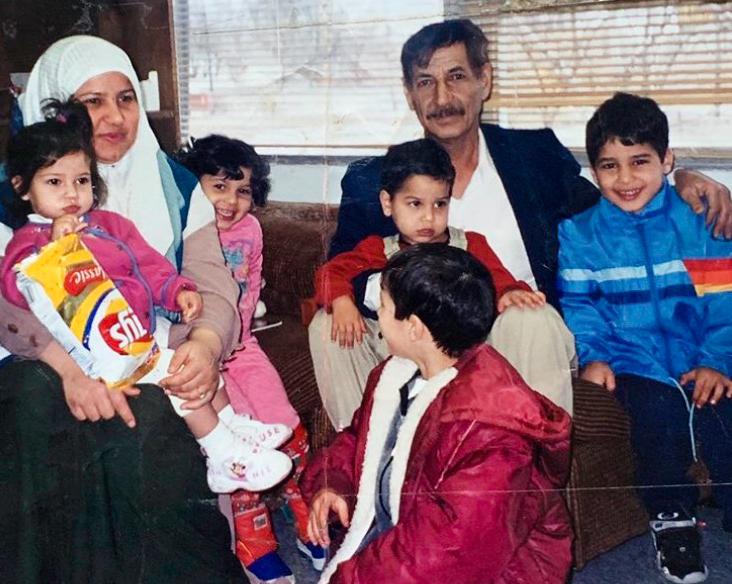

Al-Kazahy said she should not have been taken from her home. The day she and her siblings were taken, she said her father was trying to talk with two police officers, but he struggled with English – her parents were refugees from Iraq.

Nedhal Al-Kazahy, on her mother’s lap, believes that neighbors reported her Iraqi family to authorities because they were Muslim, which led to the removal of her and her siblings from their home. (Photo courtesy of Nedhal Al-Kazahy)

She remembers screaming as an officer pulled her from her father’s arms. Then she and her siblings were put in the back of a police car and driven away.

Being taken from her father is the first trauma Al-Kazahy remembers.

“The vast majority of children are removed because their families are poor, not because of sexual abuse, not because of maltreatment,” said Gladys Carrion, a former commissioner for the New York County Administration for Children’s Services. A grant report for the county said families in poverty are at greater risk of child welfare involvement.

New York County is one of the 119 counties that has used the Georgetown model with promising results. The county merged child welfare and justice data so staff members have a more complete picture of each family’s needs.

Carrion said some children do need to be removed from their families. But child welfare systems need to consider the environment they’re bringing children into and find a way to support families so they can remain intact.

Al-Kazahy’s trauma compounded throughout her 16 years in the child welfare system. She has scars from when, she said, a foster father threw shards of glass at her. She faced discrimination as a Muslim in the system, she said, adding, “Every year I spent in the system, I lost a part of my faith.”

The group home where she was sent after her rape in 2013 was even less supportive, she said, and one girl in particular bullied her.

“That was the worst possible thing the system could have done to me, to put me in a group home with high-risk girls who fight anybody,” Al-Kazahy said.

So she ran away.

Experts say group homes tend to put high-risk kids together because they aren’t accepted for placement anywhere else. Those environments are triggers for kids with existing behavioral problems, which are often induced by trauma and instability, said Barbara Duey, crossover resource director for the Children’s Law Center in Los Angeles and a well-known attorney who has represented crossover kids for decades.

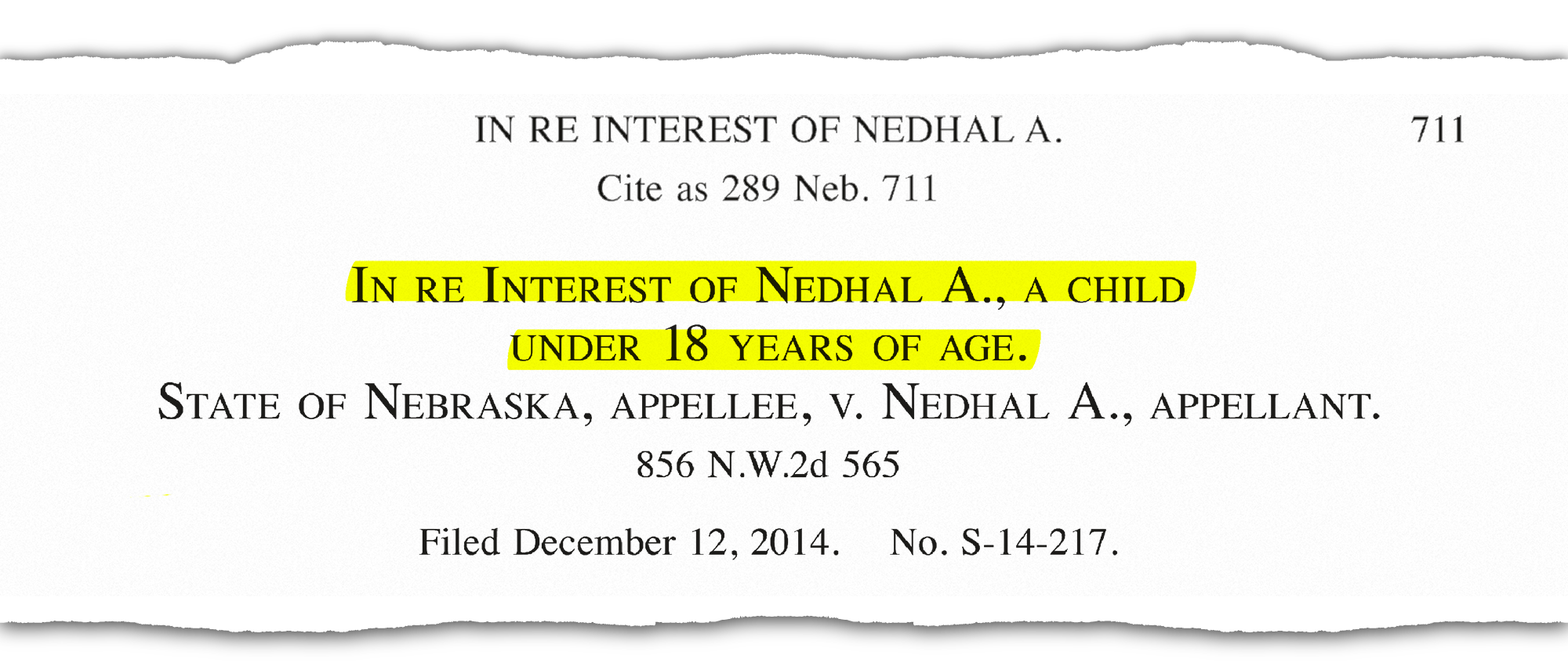

Al-Kazahy said she didn’t want to go to juvenile detention, but her state case worker advocated for it, even though she had been accepted by a therapeutic group home. Nebraska Supreme Court documents later showed that her detention was illegal.

In 2014, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled that Nedhal Al-Kazahy’s detention almost a year earlier was premature because less extreme responses, such as placement at a residential facility, had not been considered.

The mindset that the only way to keep children safe is to lock them up is a common one, said Betsy Dobbins, executive director at the Center for Children’s Rights in Jacksonville, Florida.

Curry said this practice has been abused so much that some states, including New Hampshire and Kansas, no longer allow it. He said juvenile defenders need to push courts to be more creative in finding alternatives to detention.

Al-Kazahy had already served eight months in the Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center, a high-risk detention center for girls in Geneva, Nebraska, when her incarceration was found to be illegal.

At Geneva, Al-Kazahy met Alison Brokke, a social work student who began mentoring her for a class. She said Brokke’s support was essential during her transition out of the detention center and after.

“A lot of these systems, like the foster care system and the juvenile justice system, they just remove everyone’s social supports,” said Brokke, a former caseworker in Lincoln.

Nedhal Al-Kazahy, left, met her mentor, Alison Brokke, when Brokke came to the Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center in Geneva, Nebraska, for a social work class. The two now are close friends and talk every day. (Photo courtesy of Nedhal Al-Kazahy)

Slough lives in Nashville and is in a program designed to help foster kids transition to adulthood. Reflecting on his time in the system, he said he usually didn’t know what was going on at any time, much less what was ahead.

“They said, ‘You’ll be back home in a couple weeks.’ And then it was like, ‘Oh, you’ll be back home by the end of the month,’” Slough recalled. “And then I found out, ‘Oh no, you’re going to be in a group home.’”

The uncertainty made him misbehave more, he said, because he stopped hoping that good behavior would change his situation.

“I kind of realized they’re just lying,” he said. “You’re not coming home any time soon.”

The systems that serve children in most states work in silos, said Jessica Heldman, a professor specializing in child rights at the University of San Diego School of Law.

Experts agree that to improve outcomes for crossover kids, everyone involved with their care has to collaborate more and work to identify them as soon as they enter the justice system.

Geoffrey Gaither, a magistrate judge in Marion County, Indiana, has been hearing both child welfare and delinquency cases in his Indianapolis courtroom since 2016.

Gaither said a benefit of connecting the systems is that families have to go to only one court, and they don’t receive conflicting orders from different agencies. This ensures families get the support they need from both systems, he said.

“One judge, one court, one voice, one family,” Gaither said.

His court follows the Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice model for crossover kids. That model and Georgetown’s model focus on identifying crossover kids as soon as they enter the justice system to get them and their families the support they need.

“This is about how we support young people in generations to come because what we know is that systems don’t make for good parents,” said Stewart, co-author of Georgetown’s model. “For those young people that systems feel like they need to parent, they need to do a better job in serving in that role.”

Nedhal Al-Kazahy got her "Strength" tattoo in 2018 to remind herself of everything she has overcome. It took strength, she says, to prove wrong the people who told her she would end up like her oldest brother, who was murdered when she was 14. (Portrait taken remotely by Calah Schlabach and Chloe Jones / News21)

Al-Kazahy and Slough now advocate for crossover kids. Al-Kazahy serves on the advisory board of the Nebraska Children’s Family Foundation and is a legislative page in the Nebraska Legislature.

Slough serves on the Annie E. Casey Juvenile Justice Youth Advisory Council, which is based in Baltimore, as he pursues a bachelor’s degree in psychology with a focus in social work at Vanderbilt University. Slough’s biggest recommendation for improving the system for crossover kids is making decisions that include the children and are based on relationships with them.

“There needs to be a shift and a change in the perspective of the child welfare system towards not looking at these youth as either victims or perpetrators,” Slough said. “I think we need to look at these youth as youth who are capable.”

Daja E. Henry and Chloe Jones are Donald W. Reynolds Foundation fellows, and Calah Schlabach is a Buffet Foundation fellow.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.