(Document courtesy of The Chicago Sun-Times)

In the video, Cornelius Fredericks is no match for the seven grown men piled on him. As the 16-year-old struggles to lift his left leg, one of the men immediately presses it back to the floor.

Another man is lying on Fredericks’ stomach and chest as the teenager screams, “I can’t breathe!” They remain on top of him for nearly 12 minutes until his body is limp on the floor. The adults, all employees, get up and stand over him nonchalantly for several minutes before anyone administers CPR.

The kids on the other side of the cafeteria continue eating lunch, even as Fredericks lies lifeless. Surveillance video showed staff aggressively restrained him for throwing a sandwich in the cafeteria at Lakeside Academy, a boy’s reform school in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Twelve minutes after Fredericks stops moving, an ambulance is called to rush him to a hospital. One day later, he’s dead.

Fredericks went into cardiac arrest during the restraint. The Kalamazoo County Medical Examiner’s Office found he died of “restraint asphyxia” and declared his death a homicide.

The incident is the latest controversy surrounding Sequel Youth and Family Services, a for-profit company that provides rehabilitative services to kids in the juvenile justice system. Sequel operated Lakeside Academy, a nonprofit, through a contract agreement.

“Nobody’s alarmed, including the kids,” Sara Gelser said of the cafeteria surveillance video. “And that tells me that it’s not unusual for them to restrain kids until they pass out.”

Gelser is an outspoken critic of Sequel, and as an Oregon state senator has advocated for youth justice in her state.

Sequel declined a request for an interview, but in an email to News21, a spokesperson wrote in regards to the surveillance video, “those actions are not representative of our core values of accountability, humility, and integrity. We take our obligation to meet the significant behavioral health needs of all our students very seriously and strive to improve the lives of those in our programs by providing excellence in clinical care, therapy, education, and support.”

As of 2018, 40% of residential detention facilities in the U.S. were private, housing 27% of youth, according to the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Each year, nonprofit and for-profit detention centers rake in millions of taxpayer dollars. Florida, for instance, has more than $800 million in multiyear contracts with private providers – including more than $180 million with Sequel.

In some cases, states and counties contract their secure juvenile detention centers out to private companies. Other times, private centers offer specialized treatment in less secure environments than state-run facilities.

But audits, lawsuits and accusations from youth and former staff members point to inconsistent oversight, as well as physical and sexual abuse by staff and other youth.

Michele Deitch, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, whose research partly focuses on juvenile justice, said oversight of all detention centers is lacking, but especially private facilities.

“They’re buried under another layer of bureaucracy,” she said.

For one, private centers are not required to follow open records laws as are state-run facilities, Deitch said.

In 2016, Florida cut ties with one of its largest private juvenile detention providers, Youth Services International Inc., which at the time operated seven facilities in the state. After years of abuse allegations, a whistleblower who worked for the company said it failed to provide rehabilitative services to youth inmates and regularly “forged, falsified and fabricated records” the state relied on to monitor the company under contract agreements.

As of 2017, only Pennsylvania utilized private detention centers more than Florida.

A legislative audit of South Carolina’s private juvenile centers in 2017 also found oversight lacking. The audit, instigated by a teenage boy’s death at a wilderness camp, found some contracts had no mechanism for monitoring performance or penalizing organizations for failing in their duties. The state paid contractors more than $14 million in the past fiscal year to run 10 facilities.

In an email to News21, South Carolina officials said the state has since imposed financial penalties on private centers “should terms of the contract not be fulfilled.”

In 2018, the Colorado Department of Human Services revoked the license of Rite of Passage, a for-profit company based in Utah that ran the Robert E. Denier Youth Services Center in Durango, for failing to provide safe conditions for children, falsifying reports and “substantial evidence” that employees abused children.

Even so, the company this year amended its contract with Arkansas to run all the state’s juvenile treatment centers, a move worth more than $70 million.

Regarding the Arkansas contract, a Rite of Passage spokesman said in an email to News21 that the company “will create a zero tolerance culture for any (staff member) behaviors that may be deemed as inappropriate, disrespectful, offensive or abusive.”

Alyson Clements of the National Juvenile Justice Network, a nonprofit that advocates for the removal of for-profit facilities from the juvenile justice system, among other issues, said heinous incidents have happened in both state-operated and private centers.

“The difference … is the accountability process,” she said.

When a child dies in a state-run facility, Clements said, “there is usually a public investigation; it’s usually released immediately; legislators and governors are immediately involved … so that oversight is much stronger.”

In the case of private facilities, she said, oversight is usually determined through the licensure and contracting process, which tend to be general and vary widely.

As in the case of Cornelius Fredericks, poor oversight can have significant consequences, said Geoffrey Fieger, the lawyer representing Fredericks’ family members, who are suing Sequel for $100 million.

“Unless you shine lights on insects and maggots … they proliferate,” he said during a public release of the video of Fredericks’ restraint.

In June, after reviewing the video, the Kalamazoo County Prosecuting Attorney charged three staff members of Lakeside Academy with involuntary manslaughter.

Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services began the legal proceedings to revoke Lakeside’s license after suspending it and removing all youth after Fredericks’ death.

Shortly after, Starr Commonwealth, a nonprofit in Michigan that contracted with Sequel, cut ties with the company.

“They’re just a terrible company,” said Jason Smith, director of Youth Justice Policy at the Michigan Center for Youth Justice, who called for Sequel’s removal after Fredericks’ death.

Austin Hunter, 15, was eating lunch in the Lakeside cafeteria when staff restrained Fredericks. It wasn’t the first time he had seen an excessive restraint; in fact, the kids coined the term “dirty restraint,” Hunter said, referring to restraints where staff members applied a knee or elbow to a targeted area to cause extreme pain.

“Like grind our nuts, or, like, grind our thighs and chest,” said Hunter, who spent eight months at Lakeside before it closed. He now is back in juvenile detention in Minnesota.

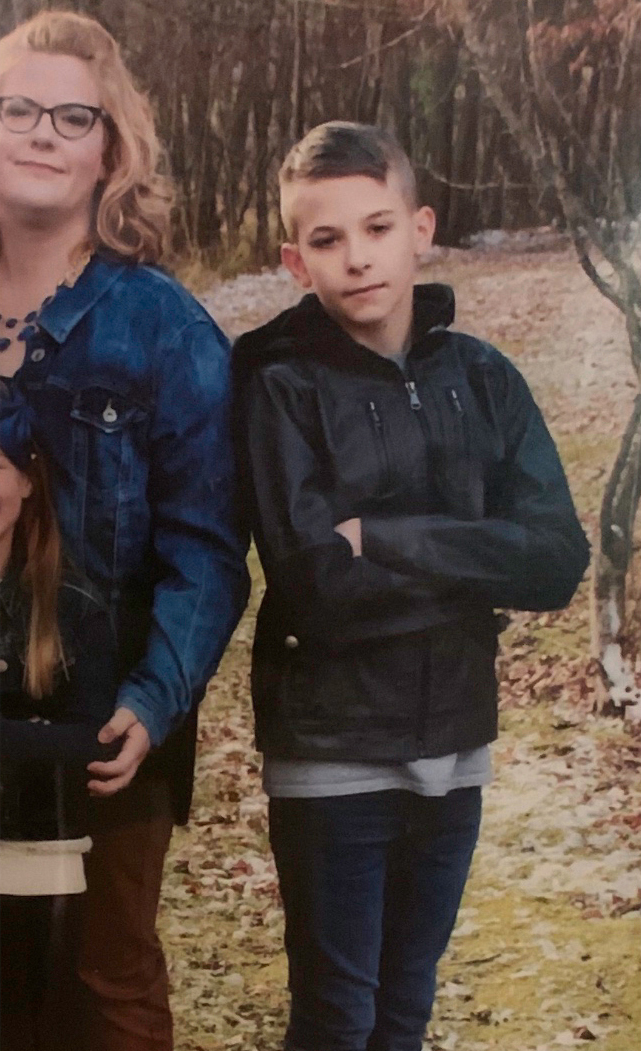

When Angela Hunter flew from Fergus Falls, Minnesota, to Michigan to visit her son, Austin Hunter, on his first day at Lakeside Academy, staff members talked about the many activities and sports available at the privately run detention center. “They made it seem really cool,” she remembers. (Photo courtesy of Angela Hunter)

Khadijah Brown worked at Lakeside Academy for a year until it closed. She said other staff members taught her how to restrain kids.

“They didn’t contract a company to come in, and, you know, really teach the restraints. It was just (another employee), and then he was like, ‘All right, I’ll teach you how to do it, you practice and I’ll be back,’” she said.

Brown said she never applied an improper restraint or witnessed one, but she “absolutely” heard stories of other staff members doing it.

Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services filed a special investigation report earlier this year that substantiated a claim that a Lakeside employee “pressed his elbow into a resident’s thigh during a restraint.”

In an email to News21, a Sequel Youth and Family Services spokesperson said “the tragic loss of Cornelius at Lakeside Academy has only served to strengthen our resolve to reduce, minimize, and eventually eliminate the use of restraints on our campuses. We are committed to making the necessary changes to ensure something like this never happens again.”

Gelser, the state legislator and advocate for Oregon juveniles incarcerated out of state, said a child’s death was inevitable based on current restraint practices.

“The only thing that’s unique about Cornelius is that he died,” she said.

“What happened to (Fredericks) happens in Sequel facilities, in juvenile justice facilities, in residential care facilities, in psychiatric facilities across the country multiple times a day … every day of the year.”

Gelser said she has interviewed kids from Sequel facilities who told her about excessive restraints, saying “sometimes they choke you out and you just fall asleep for a few minutes.”

Since Fredericks’ death, Michigan’s health department has implemented stricter rules on the use of restraints at state-licensed facilities.

But dirty restraints weren’t the only abuse Lakeside residents endured, Hunter said.

He once acted as a decoy by running into a lake to distract staff while two other boys escaped. A staff member caught up with one of the boys and slammed him to the ground, he said, and the other boy got halfway up a fence before he was pulled down. Austin said a staff member ran to the second boy and stomped on his chest.

“There were bruises all over him,” said Hunter, who suffers from fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and was originally removed from his home in Fergus Falls, Minnesota, for attacking his sister and her friend with a weed trimmer.

Another time, Hunter recalled, he grew desperate to leave Lakeside and threatened to hurt himself with a glass object, before running into his room and hiding under his bed. A staff member grabbed his arm and stomped on it, he said.

Hunter said he got up, grabbed the sheets from his bed and wrapped them around his neck, telling the staff member he was going to kill himself.

“Do you need help with that?” Hunter said the staff replied, and started pulling on the sheet.

He said a fight ensued before two other staff members entered the room. One grabbed him, slammed him to the floor and began choking him, Hunter said.

“He was like, ‘Stop resisting,’ and I’m like, ‘I’m not going to stop resisting when I can’t breathe,’” he said.

Hunter escaped the chokehold and laid in the corner of his room. Staff members kicked him twice and tore apart his room before finally leaving, he said.

Before Fredericks’ death, Michigan health officials investigated Lakeside 21 times, substantiating more than 18 licensing violations since 2017, including one incident from October 2018 when a staff member “choked, pushed and punched” a female resident.

Another report from August 2019 found an employee had been hired without a background check.

The health department mandated that Lakeside write a corrective action plan to address each substantiated abuse, but those plans were never made public, said Smith, with the Michigan Center for Youth Justice. And the contract between Michigan and Lakeside did not specify the number of violations needed before a licensing hearing is called, Smith said.

“That’s why Lakeside was able … to continue to have violations and nothing happened until there was an actual death in the facility,” he said.

The Campaign for Youth Justice is urging Michigan to establish an independent ombudsman’s office to investigate abuse claims in the juvenile justice system.

Sequel Youth and Family Services, which operates residential treatment centers across the U.S., made more than $200 million in 2016, the most recent year financial records are available. Its CEO is Chris Ruossos, who has a background in health care and was 24 Hour Fitness’ CEO from 2017-19.

Sequel contracted with Lakeside Academy, a nonprofit founded in 1907. It was Lakeside, not Sequel, that contracted with Michigan’s health department, which Gelser said enabled Sequel to maintain a level of obscurity.

“It’s a brilliant business model for Sequel because the local nonprofit and their board of directors, they’re the ones that are named when there’s liability issues,” Gelser said. “They own the property and the license is in their name. So when all of this happens, Sequel just walks away.”

In addition to the loss of its Michigan contracts, Sequel-run facilities in Utah, Tennessee and Alabama have closed since 2019 in the wake of abuse and negligence allegations.

In June 2020, the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services threatened to revoke the license of the Sequel-run facility Sequel Pomegranate, citing an unsafe environment.

And in July, the Alabama Disability Advocacy Program, or ADAP, wrote a public letter to state officials calling for the closure of all four Sequel-run facilities in Alabama. The group, which visited all state facilities that house kids with disabilities, noted widespread staff-on-youth abuse, poor education programs and filthy conditions.

“One child showed ADAP how he intentionally cut himself with a broken window frame, using his own blood to draw on a window,” the report reads. “Another child left feces on the floor, smeared it on his walls and stuck it inside a window and broken door frame. ADAP pointed out the children’s blood and feces to Sequel staff; they were both still present during the follow-up visit.”

Gelser, concerned about Oregon foster kids placed out-of-state at Sequel facilities, said she recently made an announced visit to Northern Illinois Academy, which is operated by the company.

“I immediately saw an inappropriate restraint within the first moments that I was there,” she said. “I found the facility to be dirty, disheveled. There were substances on the walls.”

But dirty facility conditions are not the only issue at Northern Illinois Academy. According to a lawsuit from 2019, an 18-year-old male resident lured a 13-year-old female resident into a bathroom and raped her while on a supervised trip to a local library. The lawsuit states that the assailant had been grooming the girl for a sexual encounter, and Sequel staff were negligent in failing to keep them apart.

Also in 2019, a judge sentenced Darius Jones, a staff member at Northern Illinois Academy, to 10 years in prison for sexually assaulting a child there.

All kids sent out of state are supposed to be monitored regularly.

Hunter said he consistently reported staff abuse at Lakeside, to his own case worker and to those of other boys. On one occasion, he said a staff member punched him in the stomach after a shouting match.

He reported it to his case worker, who called Michigan’s Child Protective Services. The agency investigated but found no proof, Hunter said. Soon after, his mother received a voice message from Hunter’s mental health worker saying that Lakeside had requested his removal within 30 days, citing a need for a “higher level of care.”

Soon after her son reported issues at Lakeside Academy, Angela Hunter received an email from his caseworker recommending his transfer, citing Austin’s need for a “higher level of care.” Angela Hunter suspects the move was motivated by the problems he was pointing out. (Document courtesy of Angela Hunter)

Austin and his mother, Angela Hunter, called the move retaliatory, and they said his phone privileges also were revoked.

“A kid that’s away from their family should be able to call their family and social workers,” Austin said.

Angela Hunter said Lakeside staff denied most of her requests to contact her son, even on Christmas. She was able to contact him on his birthday.

Austin landed in Michigan after numerous failed placements in detention centers and residential treatment programs in Minnesota, his mother said. With no other options, Austin left the state.

“I was told they basically have the pick of who they want or don’t want because there’s so many kids,” Angela said about residential placements in Minnesota.

Angela Hunter says she bought a state park pass every year so her kids could enjoy the outdoors. The trips had a soothing effect on her son Austin, who she adopted as an infant. He suffers from fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, she says, adding, “I knew that that was so good for him.” (Photo courtesy of Angela Hunter)

Smith said Lakeside Academy took kids, like Austin, who had severe behavioral issues.

“I don’t want to say the worst of the worst, because that’s the kind of negative language we don’t use, but (kids) who have been in other facilities that may have failed,” Smith said.

Minnesota is one of many states that send kids to out-of-state foster care and juvenile detention placements, typically as a last resort when no other options are available. In Oregon, for instance, the number of kids in foster care so significantly exceeded capacity that the state was renting them hotel rooms.

Companies like Sequel pursue the business of states with inadequate resources.

Gelser said her state, Oregon, spent tens of millions of dollars sending foster kids out-of-state to facilities run by Sequel – only to bring many of them back due to allegations of poor treatment and abuse.

Out-of-state placements came under scrutiny after a 2018 report by Disability Rights Washington, a Seattle nonprofit, found unsafe conditions at Clarinda Academy in Iowa, which is run by Sequel. Kids said they were forbidden to communicate with members of the opposite gender and described restraints that resulted in “back, shoulder and neck pain for several days or weeks,” according to the report.

Washington state pulled its foster kids from Clarinda after the investigation.

Austin Hunter’s stay at Lakeside cost $6,200 to $7,100 per month, according to bills obtained from his mother. She was supposed to pay a small copay but refused after learning about the abuse at Lakeside.

“They were supposed to help him,” Angela Hunter said. “They were getting paid so much money.”

Joslyn Fox is a Myrta J. Pulliam fellow, and Franco LaTona is the Don Bolles/Arizona Republic fellow.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.