(Document from Newspapers.com)

Sitting with his back to the jury, Darren McCracken, 14, sketched in a notebook using colored pencils his court-appointed lawyer had given him. He remembers barely listening as his fate was determined in a courtroom in Gosper County, Nebraska.

After three days of testimony, he was convicted of first-degree murder for shooting his mother, Vicky Bray, in 1993. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Now 40, McCracken said he was “generally unhappy” during his childhood. He described his younger self as reserved and said he just tried to “stay out of the way.”

McCracken was born in Holdrege, Nebraska, and spent much of his childhood in Lexington with his older half brother and his mother, but after he finished fifth grade, the three and McCracken’s stepfather moved 15 miles south to Smithfield. He said his half brother was very abusive and they often fought.

Darren McCracken, 11, front left, and his mother, Vicky Bray, 32, back left, pose for a family photo celebrating his great aunt’s birthday in 1991. Two years later, McCracken shot Bray twice as she slept on the couch. (Photo courtesy of Darren McCracken)

When McCracken was 11, he climbed the exterior ladder of a grain elevator with the intention of jumping off the top, but he never told anyone. At 12, he ran away for the first time, taking a backpack filled with clothes, blankets and his stepfather’s .38-caliber derringer pistol.

“At that time, I didn’t realize that I was suffering from depression. I didn’t know there was such a thing,” McCracken said.

In 1993, Bray became worried about her son because he was drawing violent pictures at school. The family visited Maureen Lauby, an independent mental health practitioner in Lexington, a handful of times.

Lauby remembers McCracken drawing “a bombing airplane” but doesn’t recall his sketches being “very personalized” or portraying human beings.

“I was a bit concerned, but not terribly,” Lauby said.

When Lauby first met McCracken and his mother, she was struck by how much their voices and laughs sounded alike.

“They loved each other, it was quite clear,” she said. “They were very close.”

She described McCracken as a bright, gangly 13-year-old who was “quite personable and spoke easily,” and said she immediately took a liking to him.

Lauby and Bray discussed having the boy evaluated and the two of them went to social services together in spring 1993. The social worker suggested Bray delay the evaluation until her husband was eligible for health insurance in July.

Lauby said Bray was disheartened by the delay and the family discontinued their counseling sessions.

Darren McCracken poses for a portrait in the living room of his first apartment in Lincoln, Nebraska, in July 2020. After 26 years in prison, McCracken is living on his own for the first time in his life. (Portrait taken remotely by James Wooldridge / News21)

McCracken had run away the year before and Bray blamed herself. Lauby said McCracken was planning to run away again but didn’t want to upset his mother again.

On July 1, 1993, McCracken shot his mother twice with the derringer as she slept.

“I thought that, well, if she were to die, then she would go to heaven and be happy and nothing I did would make her unhappy,” McCracken recalled. “As an adult, obviously, that doesn’t make any sense, but as an unstable 13-year-old, it made perfect sense.”

But as he held the gun, he wasn’t sure he could go through with his plan.

“When I squeezed the trigger, I wasn’t even aware that I had done it,” McCracken said. “The gunshot actually surprised me.”

McCracken began to second-guess himself and considered calling 911.

“I decided it was something that I had to finish, so I shot her again,” McCracken said.

He ran upstairs, grabbed the bag he packed with clothes and ammunition and walked to a farmer’s house a mile down the road. The walk, McCracken said, was filled with “a lot of crying and a lot of praying.”

McCracken asked the farmer for a ride to the Lexington Police Department, where he turned himself in.

“I told them where to find the gun that I had thrown away. I told them where to find her because I thought she had died,” McCracken said.

Critically wounded, Bray was hospitalized first in Lexington and then in Kearney, where she died July 15.

“I didn’t realize she was still alive until they charged me with attempted first-degree murder,” McCracken said. “That was my original charge until she passed away, and then they changed it to first-degree murder.”

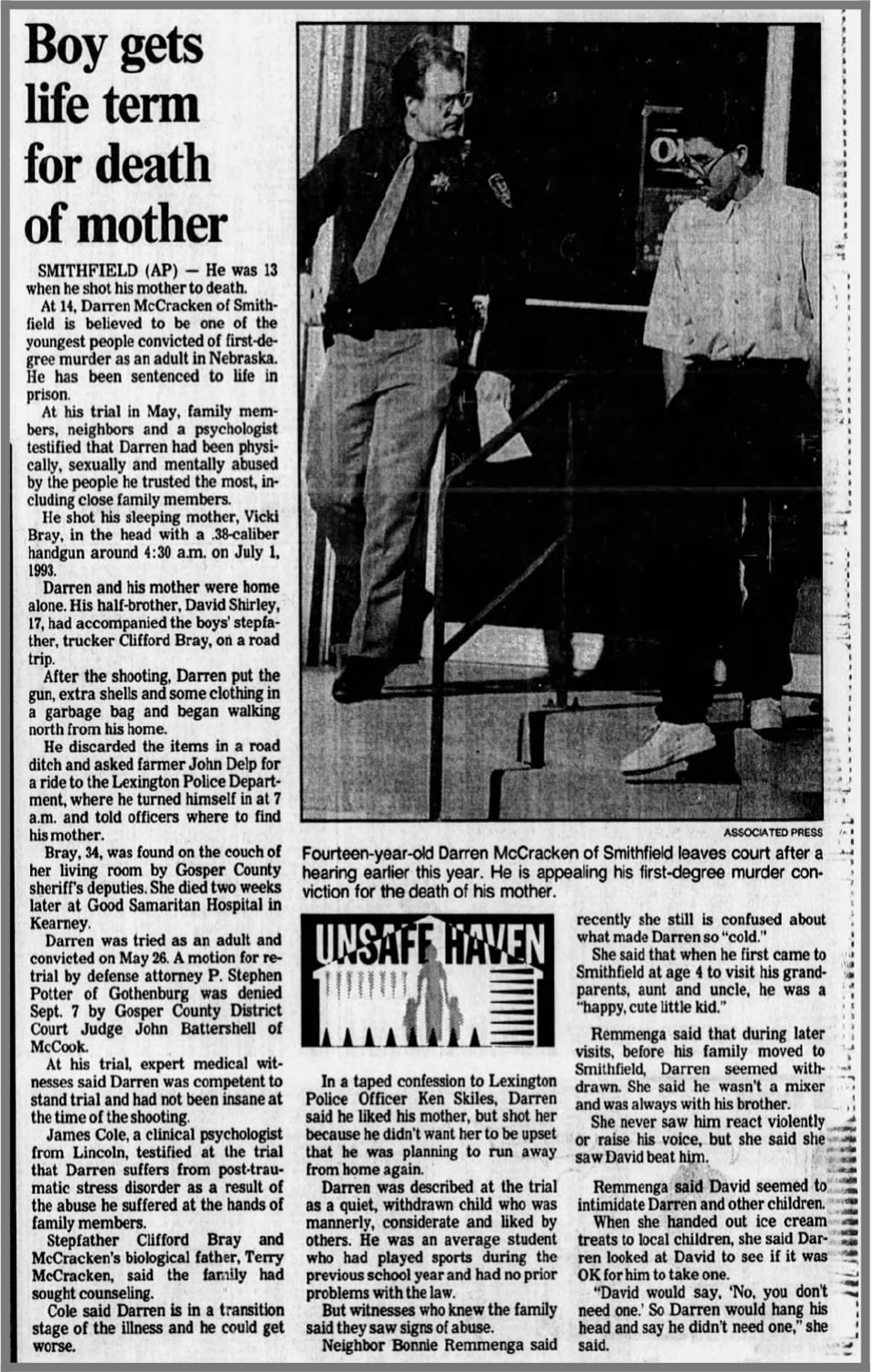

Two months after Darren McCracken’s life sentence the Lincoln Journal Star published this article on Oct. 20, 1994. (Photo from Newspapers.com)

During trial in May 1994, police Sgt. Ken Skiles testified that McCracken was calm and unemotional when he turned himself in, and in a taped interview that was played for the jury, the boy said, “I think I’ve got some big troubles.”

McCracken is believed to be one of the youngest people in Nebraska to be tried for first-degree murder in adult court, according to the Lincoln Journal Star.

“It was boring and I understood that it was important to me, but I didn’t feel like I had any control over it so I just kind of blocked it out,” McCracken said of his trial.

After deliberating for about two hours on May 26, the 12-member jury found him guilty of first-degree murder. At 14, McCracken was sentenced to life without possibility of parole.

“I didn’t truly understand what it meant until several years later that I was going to spend if not all my life, then a majority of my life in prison,” McCracken said.

When McCracken was 16, he was moved from a diagnostic and evaluation center to the Lincoln Correctional Center, a medium/maximum custody facility for men, where he earned a GED diploma.

“I was very disappointed because I finished it, I didn’t get any party and then like six months later, they started having parties for GED graduates,” McCracken said. “I didn’t get a cap and gown, I didn’t have a cake – honestly, the cake is what I was really worried about.”

Soon after, he began taking college classes through Southeast Community College in Nebraska, and completed 40 credits.

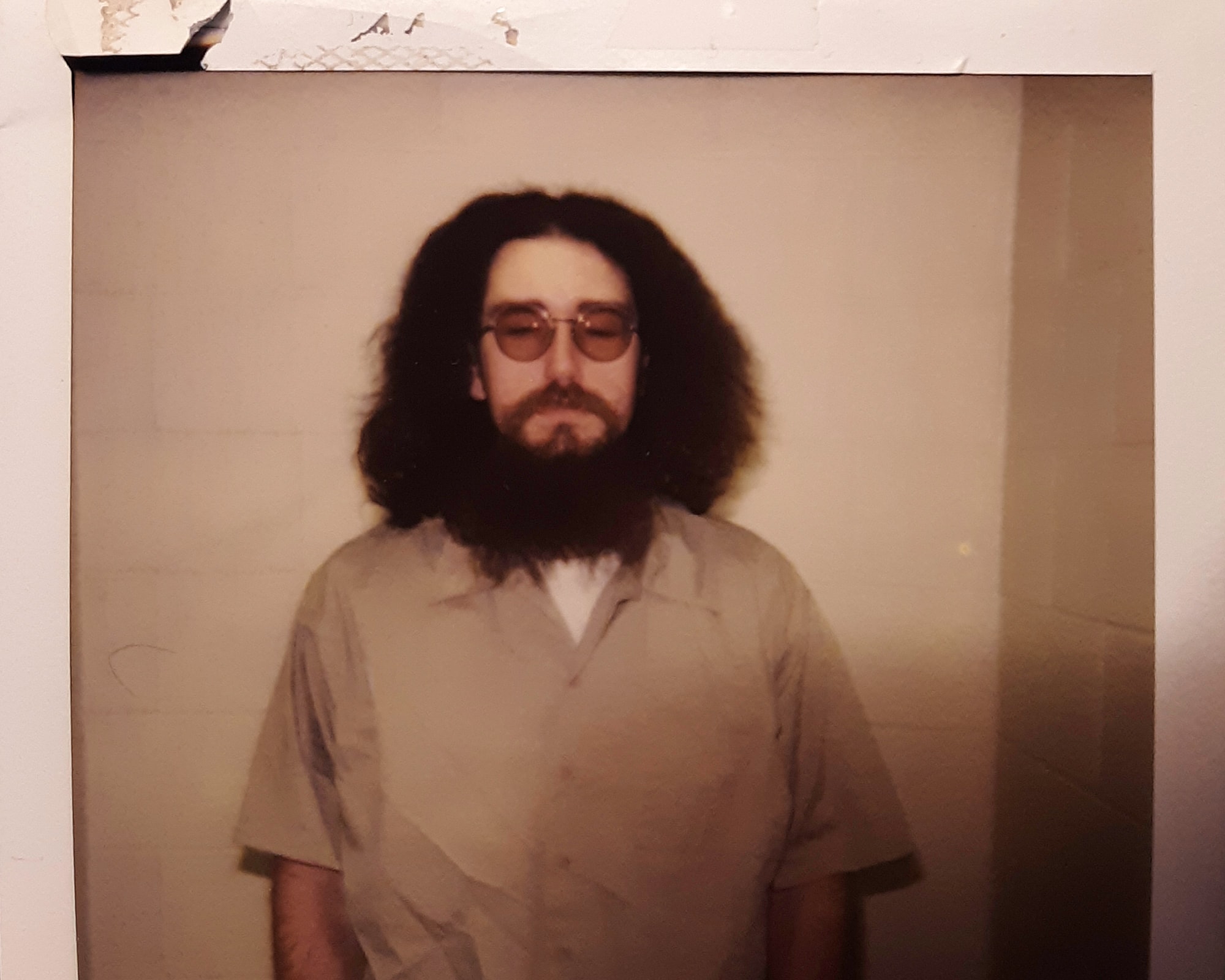

Darren McCracken at Nebraska’s Tecumseh Correctional State Institution in December 2003. The previous year, he had noticed his hairline was receding and decided to grow it out one last time. In February 2004, after two years, he cut it and kept it short ever since. (Photo courtesy of Darren McCracken)

In January 2002, McCracken was moved to Tecumseh State Correctional Institution.

Lauby, his former counselor, asked to visit McCracken when he was about 18. The two began having weekly phone calls, monthly visits and letter exchanges.

“He just haunted me,” Lauby said. “As time went by, I thought about him more and more and I decided that I would make a commitment to visit him.”

Lauby said McCracken expressed regret for killing his mother.

“I think that it’s such a deep, deep sorrow that he doesn’t talk about it,” Lauby said.

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court case Miller v. Alabama ruled that mandatory sentences of life without the possibility of parole for juvenile offenders were unconstitutional. McCracken said he watched as other juvenile offenders were released or resentenced, but he was one of the last.

“All of my friends that had gone off to get resentenced, most of them got the equivalent of life, just in numbers,” McCracken said. “So I didn’t think I was going to get a decent sentence.”

But on Feb. 28, 2018, McCracken was resentenced in Gosper County Court to no less than 51½ years and no more than 75 years. He received credit for 24 years served and became eligible for parole in 2019.

“I was pleasantly surprised … OK, I was shocked,” McCracken said. “I was shocked and a little scared. When they said I was paroled, I kept asking, ‘So you mean I can leave?’”

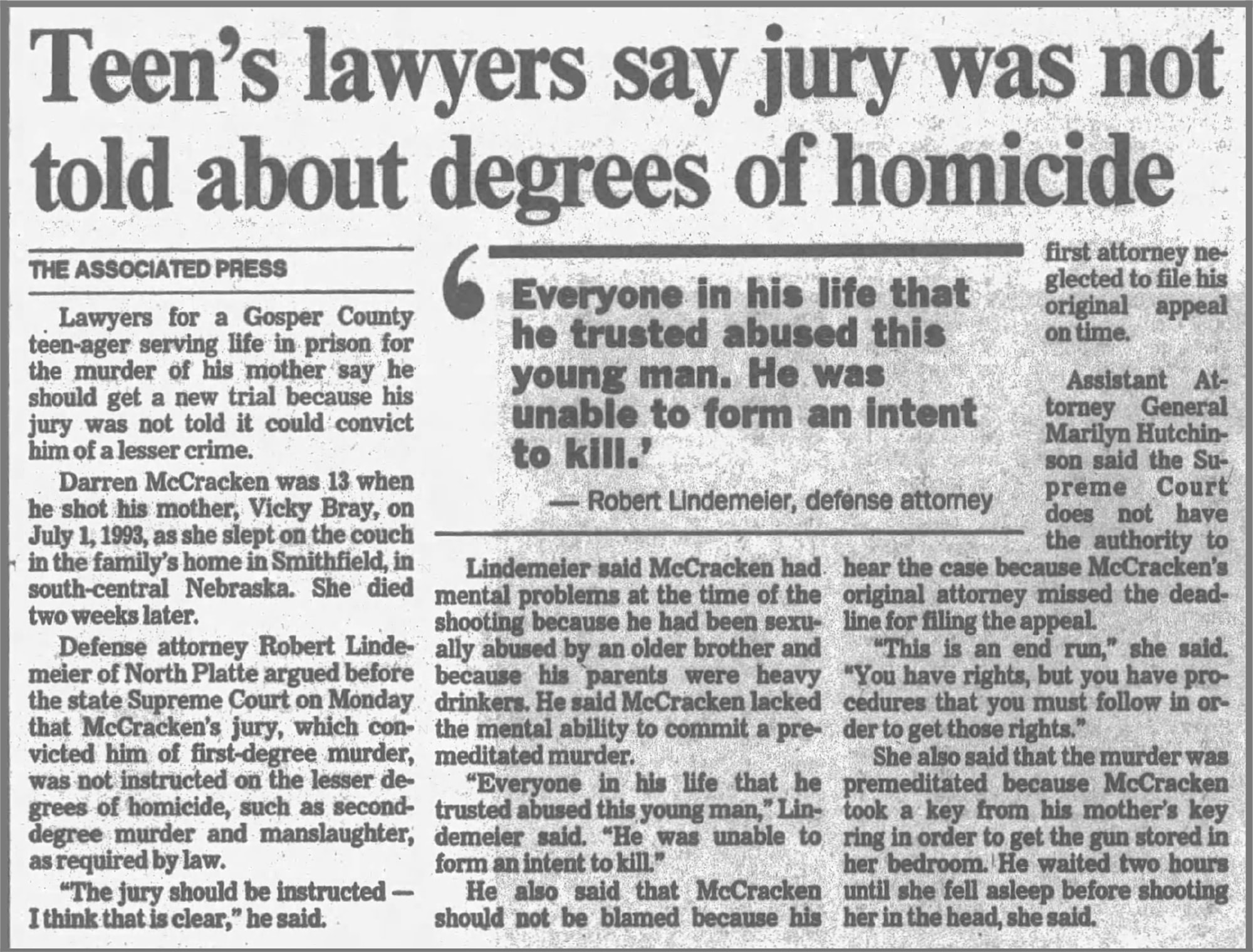

This article in the Lincoln Journal Star on Oct. 6, 1998, was published four years after Darren McCracken’s murder conviction. (Photo from Newspapers.com)

McCracken didn’t believe it.

“I still kept thinking that they had made a mistake,” he said. “I felt that way for about the first two weeks. I kept waiting for someone to realize they’d made a mistake and come get me.”

McCracken found a job in Lincoln, Nebraska, through a work-release program in May 2019. He had put out “hundreds of applications” with help from the American Job Center and the Mental Health Association.

“I got almost no responses,” he said, “and the few responses I did get, I didn’t get the job because of my conviction, because of my lack of a driver’s license, or I found out I couldn’t take the job because it wasn’t anywhere near a bus stop.”

His first few jobs were in construction and janitorial work.

McCracken was released from Tecumseh in October 2019 with a couple of books, a few clothes and his paperwork. He immediately went to Honu Home, a peer-operated transitional program, to begin settling into his new life.

McCracken said because he spent most of his formative early teens in a cell talking to himself, it is difficult to socialize.

“There’s certain parts that I’m missing and don’t realize this until I’m around people,” McCracken said. “I just feel like I’m missing something, like there’s some part of human socialization that I just don’t get.”

He said he still isn’t happy.

“I had worked it up in my mind that just being out and having a job was going to be enough, that I was going to be happy. Well, I’ve been out and I have a job and I’m still not happy,” McCracken said.

In June, McCracken moved into his own apartment. At 40, he’s living alone for the first time.

“There’s so many things I didn’t realize I was going to need, like one of those little mats for the bathtub so you don’t slip in the shower,” he said.

Many times he asks a friend to go with him when encountering new situations.

“When I do go places or do things on my own, I do occasionally get overwhelmed. It stresses me out, it gets me frustrated,” McCracken said. “I don’t like not being able to figure things out and when I can’t figure things out, I feel bad, I feel stupid.”

McCracken has worked a stable job at a fast-food restaurant for a little more than a year. He likes the people he works with but not the work he does.

“When I’m there, I just think about not being there, but when I’m not there, I don’t know what to do with myself,” McCracken said. “I don’t want to go back to prison, but at least in prison I knew what to do.”

McCracken said he doesn’t have a purpose, which bothers him.

“I feel trapped because I can’t seem to get a job I actually want and I feel like I’m moving at a snail’s pace,” he said.

In mid-July, McCracken accepted a job at Honu Home working as a peer specialist. He said the main objective of his job is to be available to assist people with whatever it is they need, whether that’s paperwork or someone to vent to.

“I’m glad that I get to go to work and do a job that might be a little bit more fulfilling than serving food to people,” he said.

He still has not forgiven himself.

“It’s something that still bothers me. It’s gotten to the point where I don’t think about it everyday but I don’t think it’s something I’m ever going to stop regretting,” McCracken said.

If you or someone you know is in need of help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or text 741-741 to connect with a trained crisis counselor right away.

Our content is Creative Commons licensed. If you want to republish this story, download a zip file of the text and images.